Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (13 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

HERMANN GRAF

Gollob’s record was passed six days later by Hermann Graf who, on 2 October, reached 202. Graf’s record was remarkable. After serving as a flying instructor, he was posted to

9/JG 52

as a

Feldwebel

in July 1941. His first victory came on 3 August, and from that time he never looked back. The four weeks prior to passing the 200 mark saw him account for no fewer than 75 Russian aircraft. This was his high-water mark. Wounded shortly afterwards, he returned to fly in the air defence of the Reich, where he accounted for ten heavy bombers. Towards the end of the war he returned to

JG 52

as

Kommodore

but failed to add to his score.

The names that really stand out during this period are Gerhard Barkhorn and Günther Rall, both of

JG 52.

This pair survived the war as the second and third ranking fighter pilots of all time, with 301 and

275 victories respectively, but the bulk of their victims came in the first half of the Russian campaign.

GERHARD BARKHORN

Gerhard Barkhorn’s combat début, in the Battle of Britain, was singularly inauspicious. He not only failed to score but was shot down twice, on one occasion baling out into the Channel. Not until his 120th sortie, on 2 July 1941, did he open his account. Once started, his progress was steady. His hundredth victory came on 19 December, and his best ever single sortie, on 20 July 1942, yielded four victories. After this his scoring rate slowed, and the two hundred mark was not reached until 30 November 1943. Barkhorn’s comments on his opponents are revealing:

Some of the Russian pilots flew without looking to either side of them, or back behind their tails. I shot down a lot of them like this who didn’t even know I was there. A few of them were good, like other European pilots, but most were not flexible in their response to aerial fighting.

While not explicitly stated, it can be inferred from this passage that Barkhorn was a master of the surprise bounce, the diving attack from the sun, or the fast closure from astern and slightly low. At the same time, he did not eschew the classic manoeuvre combat, especially when flying the Bf 109F which he favoured, even the variant with the single 15mm cannon. But not all Russian pilots were easy:

Once I had a forty-minute battle in 1943 with a hot Russian pilot and I just couldn’t get him. Sweat was pouring off me just as though I had stepped out of the shower, and I wondered if he was in the same condition. He was flying a LaGG-3, and we both pulled every aerobatic manoeuvre we knew, as well as inventing some new ones as we went. I couldn’t nail him, nor could he get me. He belonged to one of the Guards Regiments, in which the Russians concentrated their best pilots …

A one-versus-one combat lasting forty minutes must be something of a record. Usually other fighters would be in the vicinity, and they would intervene, or, on the rare occasions that singletons chanced to meet, one would normally have a decisive advantage in height or position. The inference here is that both pilots fought defensively, careful not to get into a false position. That Barkhorn tempered aggression with caution (possibly ingrained by his experiences of flying against the RAF) can be assumed from two facts. First, sorties in which he scored multiple

victories were fewer than those of many other

Experten

, and secondly, in 1,104 sorties he was downed only nine times.

But in May 1944, his score at 273, very tired and rather careless, Barkhorn was jumped by a Russian fighter and put out of action for four months. On his return to

JG 52

he brought his score to 301, then was transferred to the West as

Kommodore

of

JG 6.

No further successes followed, and he then joined Galland’s

JV 44

, flying the Me 262. Engine failure on his second sortie in the jet resulted in a crash-landing in which he was once more badly injured.

Postwar, Barkhorn returned to flying with the new

Luftwaffe.

In the mid-1960s he ‘dropped’ a hovering Kestrel (forerunner of the Harrier) which he was evaluating. As he was helped out of the battered jet, he is reported to have muttered

‘Drei hundert und zwei

[302]!’

GÜNTHER RALL

Of all the

Experten

, Günther Rall was probably the best marksman, able to score hits from extreme ranges (although he preferred to get in close) and crossing angles. His mastery of deflection shooting was instinctive, and it amazed those who saw it (

Fig. 13

). His first victory was a French Hawk 75 on 12 May 1940, but, like Barkhorn, he flew during the Battle of Britain with little success. It is a strange fact that the top-scoring

Jagdgeschwader

of the war, containing such luminaries as Barkhorn and Rall, Beisswenger, Dickfeld, Grislawski, Dammers and Eichel-Streiber, who racked up over 1,000 victories between them, failed to produce an

Experte

of note during this period. But in the early days of ‘Barbarossa’ things changed radically.

Rall, by now

Staffelkapitän

of

8/JG 52

, started the war at Constanza, Romania, his task to protect the oil refineries. His first encounter was with a formation of Soviet DB-3 bombers:

When they saw us coming out to meet them—we were still below them climbing—they turned back east, some dropping their bombs. They were silver-coloured or white, and now the chase was on. We attacked from below and behind and shot many of them down. I aimed at the right engine of one and set him afire. He went into a spin. We continued our attacks until we were about out of fuel, and had to turn back toward the base. Since they had no fighter escort it was simple.

Over the next few days Rail’s unit accounted for between 45 and 50 Russian bombers. They then returned to the

Gruppe

,

III/JG 52

, and took part in the offensive in southern Russia. The budding

Experte

soon increased his score to 36, shooting down a Soviet fighter in flames late on 28 November. In the near-darkness the temptation to watch it go down proved irresistible. Distracted by the sight, and dazzled by the comet-like trail, he was shot up from behind by another Russian. In the ensuing crash-landing, Rall broke his back.

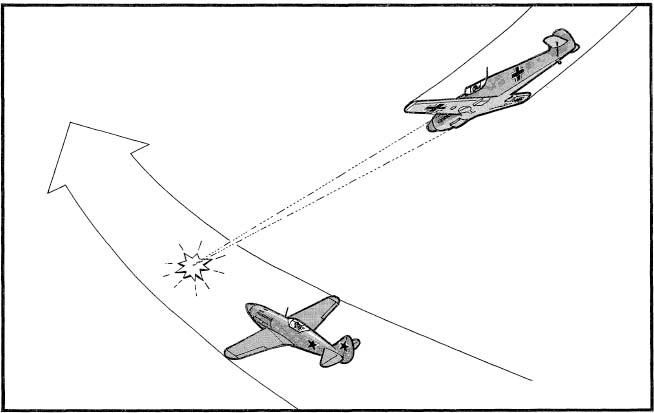

Fig. 13. Deflection Shooting

Bullets took a second or so to cover the distance to the target

,

by which time it was no longer there. Deflection shooting was the art of aiming ahead of the target

,

so that it arrived in the same place and the same time as the bullets. Russian Front

Experte

G

ünther Rall was widely considered the best deflection shot in the

Jagdwaffe.

It was eight months before he returned to the front, and he quickly made up for lost time. In a little over two months, Rall accounted for 64 Russians to reach the century mark. By August 1943 he reached 200 and, after knocking down 40 Russians in October, reached 250 the following month, only the second pilot to do so, just six weeks later than Walter Nowotny (final score 258 victories).

While Rail’s incredible gunnery skills have already been mentioned, one of his victories came as the result of a mid-air collision. Uncertain whether a bogey was a Russian or an FW 190, which was new at the front at that time, he closed with it to make sure:

I couldn’t see the colour and insignia on the other aircraft, only the silhouette. So I chased him at high speed, pulled up, and at that moment saw the aircraft against the ground instead of against the sun. The red star was glaring back at me from his fuselage. I couldn’t turn away, because otherwise he would just have turned too, and shot me down like a duck.

I turned back from the left and down, pulled the trigger, and there was an ear-splitting, terrifying crash. Collision! I bounced on this Russian from above. I cut his wing with my propeller, and he cut my fuselage with his propeller. He got the worst of it, because my propeller went through his wing like a ripsaw.

Mortally damaged, the Russian spun down, leaving Rall to pull off a belly-landing from which he was able to walk away.

His score at 273, Günther Rall was transferred to the West in March 1944 as

Kommandeur

of

II

/

JG 11.

It was not a lucky move. Like so many of his Eastern Front comrades, he was able to achieve little against the hordes of American bombers and fighters and on 12 May he was shot down by a P-47, losing his left thumb in the process. Infection from his wound kept him

hors de combat

until November of that year, and a staff job followed. His final combat appointment was as

Kommodore

of

JG 300

in March 1945. He was shot down five times in the course of 621 sorties, and his final score was 275, making him the third highest scorer of all time.

GÜNTHER SCHEEL

No work on fighter pilots can afford to pass without at least a mention of

Leutnant

Günther Scheel. For sheer sustained mass destruction he is unrivalled. A few high-scoring

Experten

went through purple patches in which they matched his strike rate, but only after they had spent time playing themselves in and learning the game.

Not so Scheel. He joined

3/JG 54

in the spring of 1943 and almost immediately started scoring consistently, so much so that in just 70 sorties he notched up 71 confirmed victories—a record that was never surpassed. His luck ran out on 16 July when he rammed a Yak-9 near Orel at low level and his aircraft crashed and burned.

| 4. WESTERN FRONT. 1941–43 |

With the onset of winter 1940/41, the daylight battles over south-eastern England had gradually fizzled out, leaving the German bomber force to continue the air war against the island fortress by night. Combatants on both sides expected the daylight assault to be renewed with the coming of better weather in the spring of 1941, but this was not to be. As noted in the previous chapter, Hitler was by now looking eastward.

Generalleutnant

Adolf Galland later commented that the campaign against England was never one of Hitler’s original war aims. It was merely a stone which had rolled in his way and it had either to be removed or to be by-passed. In any case, it was something which could not be allowed to interfere with the main objective, the destruction of Bolshevism. Having failed to remove the stone in the summer of 1940, he now chose to by-pass it. If, after the conquest of the Soviet Union was complete, the islanders were still recalcitrant, they could then be dealt with by a Germany enriched, in the words of Hermann Goering, by the inexhaustible strategic resources of Russia.

Following heavy losses sustained in the Battle of Britain (

III/JG 52,

for example, had only four of its original complement of pilots left by October 1940), each

Jagdgeschwader

in turn withdrew to Germany to re-equip and to train the youngsters. The Bf 109F-2 entered service with

III/JG 26

in May 1941, and other units soon converted to this model, which in some ways was superior to the newest British Spitfire, the Mk V.

Offensive action on the Channel coast during the first half of 1941 amounted to little more than skirmishing, with penny packets of German fighters carrying out sweeps in

Staffel

or even

Schwarm

strength. The RAF was of similar mind, putting a cautious toe in the water and probing the strength of the German air defences. Meanwhile many

Jagd

geschwader

were unobtrusively transferred to the East, leaving only

JG 26

‘

Schlageter

’, commanded by the redoubtable Adolf Galland, and

JG 2

‘

Richthofen

’, commanded from July 1941 by Walter Oesau, to hold the ring on the Channel coast.

The air weapon must be used if it is to keep its cutting edge, and so RAF Fighter Command instituted a policy of ‘leaning forward into France’. This took several forms. ‘Rhubarbs’ and ‘Rangers’ were incursions by small numbers (typically a pair) of fighters at low level, seeking targets of opportunity. Far more important were ‘Rodeos’ and ‘Circuses’. These differed only in whether they accompanied bombers. A Rodeo was a pure fighter sweep, typically by one or two wings of three squadrons (36 fighters) each. Provided it was identified as such in time, a Rodeo was left strictly alone by the

Jagdflieger.

This followed the pattern of the previous year, when the

Frei-jagd

of the

Luftwaffe

over southern England had been largely ignored by RAF Fighter Command. The Circus contained bombers, and this fact was enough to force the

Jagdgeschwader

to intercept. Even though only a handful of bombers was involved, and damage to their targets was often minimal, Circuses could not be ignored. To do so would simply have encouraged the RAF to step up the weight of attack, with consequent heavier damage.