Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (45 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

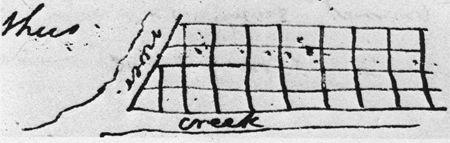

Grid Thinking

Thomas Jefferson’s 1790 plan for a capital city on the site of Carrollsburg, District of Columbia, echoed plans for Roman garrison towns. The grid would be repeated in cities across the continent.

(From papers of Thomas Jefferson, untitled sketch in the margin of a manuscript note, “Proceedings to be had under the Residence Act,” dated November 29, 1790, LC-MS)

The result was that in most neighborhoods, the streets themselves became the only shared public space. As they came to be dominated by cars, the public living room—and the village that might have been born within it—disappeared.

The grid has its defenders, especially when compared with the stunning inefficiency of the freeway and cul-de-sac development of sprawl. New Urbanists admire the clarity and connectivity that can make grid neighborhoods so conducive to walking. Traffic engineers point out that a tight grid of arterial roads is less vulnerable to the nightmarish delays that accidents can cause on dendritic systems and freeways.

But the imposition of the grid or any other plan from on high has another, ultimately more profound effect on the people who must inhabit it: it estranges them from the process of shaping their own world.

“None of the people who have ever lived on my street had a say on how it was laid out. None of them ever held a vote and said, ‘Let’s make this bilaterally symmetrical, and let’s make the rules on this side of the street the same as on the other side of the street. Let’s make sure the intersections won’t be the gathering places that our ancestors made back in the lands that we came from,’” Lakeman told me. “How many of us actually said, ‘Hey, let’s not have even one public square in the typical American neighborhood,’ where in the typical village there were many.”

Whether or not you share Lakeman’s conception of the evils of the urban grid, he does identify that great irony of the American city: a nation that celebrates freedom and weaves liberty into its national myth rarely gives regular people the chance to shape their own communities. Municipal governments, often with the counsel and assistance of land developers, lay down community plans complete with restrictive zoning long before residents arrive on the scene. Residents have no say about what their streets and parks and gathering places will look like. And once they move in, it is illegal for them to tinker with the shape of the public places they share, or, as I have illustrated, to use their homes for anything beyond the dictates of strict zoning bylaws.

Most people in wealthy cities do not make their own homes or neighborhoods. They simply decorate and inhabit the dwellings they are offered. And we know that the ultimate villageless city—sprawl—has effectively sapped its residents of social and political wherewithal. As I have shown, people who live in sprawl are among the least likely of Americans to volunteer, vote, join political parties, or rise up and raise hell. There are many reasons for this apathy; not least among them might be genuine contentment. But the fact is, it’s hard to find the agora in the dispersed city. You can’t hold a demonstration in a Walmart parking lot or inside a Starbucks. Scant few neighborhoods in North America feature places that draw people together regularly for anything other than buying stuff.

This is why what happened when Lakeman got back to Sellwood that spring was so revolutionary. He challenged his neighbors to take control of the shape of their community.

First, Lakeman and a few friends built a ramshackle teahouse of salvaged wood and old windows around the base of an old tree on his parents’ property on the corner of the intersection of Southeast Sherrett and Southeast Ninth, and they invited the neighbors to come for tea. Sellwood had never seen anything like it. Curious, people from up and down the blocks popped in. As spring grew lush and the cottonwood seeds began to fly in the breeze, a few dozen people would arrive to share Monday-night potluck dinners. By summer, there were hundreds.

The neighbors got to talking about the state of their neighborhood: the commuters who roared through the grid on their way to the Sellwood Bridge, the kids who had been struck by cars while trying to reach a nearby park, and the fact that none of them had ever talked to each other before. To Lakeman’s delight, one Monday evening the crowd pushed right out into the middle of the intersection, and the cars stopped, and some of the people started to dance in the warm evening air.

When Portland’s Bureau of Buildings ordered the teahouse, an unauthorized structure, torn down, the neighbors looked to the intersection and imagined a village square that was as desirable as it was forbidden.

The way that neighbors remember it now, someone’s kid, a girl of thirteen, gathered the other children around a map of the four blocks around the intersection. The kids drew lines on that map with red felt-tip pens, connecting neighbors. There was a chef, and lots of people who liked to eat. There was a social worker, and people who had social problems. There was a musician, and people who liked music. There was an electrician. A plumber. A roofer. A designer. A landscaper. A carpenter. A contractor. Then they added the stay-at-home parents and the kids, too. Eventually the map was so crisscrossed with red it was hard to read. All these people drove out of the neighborhood to eat, to socialize, to work, and to spend. “We realized that we had a full-on village right here,” Lakeman said. “All we were missing was a central place to connect.” In other words, the neighborhood did not have a human resources problem. It had a design problem.

The neighbors gathered one weekend in September, thirty of them, and they brought paint, and they coated the asphalt in concentric circles radiating from the manhole at its center so that all four corners were linked. From then on, the intersection would be a piazza. They called it Share-It-Square.

Portland’s Office of Transportation promptly threatened to fine the neighbors and sandblast the circles off the street. The intersection was a public space. “That means nobody is allowed to use it!” one city staffer infamously declared.

But Lakeman charmed city councilors with his village tales. The mayor pulled rank on the city’s engineers. Within a few weeks the square had a conditional permit.

The neighbors built a telephone booth–size library on one corner of the intersection so people could come and trade books. They built a message board and chalk stand on the northeast corner, and a produce-sharing stand on the southeast, and a kiosk on the southwest with a big thermos that they agreed to keep full of hot tea.

Eventually the lines between public and private space began to blur. Just as the neighbors had appropriated the public right-of-way, so they began to open their own lots. One couple built a community sauna in their backyard. Fences between yards came down. People from blocks away came to help themselves to vegetables from the produce stand—and leave other greens in their place. People went out of their way to help one another. One elderly woman left town for a week and returned to find that her neighbors had painted the peeling exterior of her house.

I visited Portland on the spring day when the piazza was getting its annual new coat of paint. There were cans and brushes and kids all over the street, smearing the asphalt with coats of electric pink, turquoise, and leaf green. There was Wayne, a homeless bottle collector, pausing for a smoke and a chat on the cob bench the villagers had built, with Pedro Ferbel, the guy who built a community sauna in his backyard. A young mother put down her paint roller and told me that she had moved nearby for the sake of her daughter, who had met most of her friends around this intersection. Betty Beals, a woman with long gray hair, poured me a cup of tea from the thermos at the covered kiosk and told me how she once felt scared to walk these streets because she just didn’t recognize or trust the people she encountered. Not anymore. Other people spoke of spending less money than they used to—they borrowed tools from friends, for example, and were more likely to host neighbors for dinner rather than going out. This was partly a result of the financial crisis that had hit the country so hard, but it would not have happened if the door of conviviality had not been opened.

The place felt like that mythical, possibly imagined past in which everybody knows your name and cares about how you are. It felt almost cartoonlike, perhaps because the scene is so rare these days anywhere but on TV, yet this scene was real.

Intersection Repair

Neighbors repaint the “piazza” on their intersection in Sellwood, Portland. The intervention spawned a movement known as City Repair.

(Charles Montgomery)

So is the psychological effect of intersection repair. We know this thanks to Jan Semenza, a Swedish-Italian epidemiologist who arrived to teach public health at Portland State University a couple of years after Share-It-Square was born. Semenza had his own special interest in getting people together. The story of his introduction to the geography of loneliness is worth remembering.

Semenza had just begun training as an investigator at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta in the summer of 1995 when an unprecedented heat wave struck the American Midwest. By July 13 the temperature in Chicago had hit 106 degrees. The heat index—a combination of heat and humidity that measures the temperature a typical person would feel—soared above 120. Roads buckled. Apartments baked. Kids riding buses to summer school programs got so nauseated from heat and dehydration that they had to be hosed down by the fire department. Other people were so desperate to cool down, they forced open thousands of fire hydrants. When crews came to shut the water off, the street bathers threw bricks and stones at them. By July 15 the old and the sick were running out of steam. More than three hundred people died from the heat that day alone.

The CDC sent Semenza to Chicago to figure out who was dying, and why. By the time he flew into O’Hare, seven hundred people had expired from heat-related illness. Semenza and his team of eighty investigators, including his wife, Lisa Weasel, fanned out across the city, interviewing the families and friends of those who died.

On one of their first days out, Semenza, Weasel, and a colleague attempted to learn about a middle-aged man who had died in his residential hotel room. They couldn’t locate the man’s family or any of his friends, so they approached the manager of the run-down apartment hotel where the man lived. The manager sat in a little booth in the hotel’s cramped lobby. The air was thick and heavy. The lobby walls were painted red and the lights dim. Coming in off the street was like entering the maw of a great beast, remembers Semenza.

The manager wouldn’t let the investigators climb the stairs. There was no point, he told them. The dead man had left no trace, and his room had already been rented.

“What can you tell us about him?” asked Semenza.

“Nothing. I don’t know anything about this guy,” replied the manager gruffly.

Did he have family? None that visited. Friends? Nope. The guy had never entertained a single guest.

Semenza remembers the heat pressing down from the ceiling and the manager scowling. Semenza’s shirt was soaked in sweat. He tried again. Surely there was some detail, something that could be learned about the deceased.

“No! There’s nothing to be known about this man,” the manager replied. “He was totally alone. He was no one.”

Semenza heard that story of solitude over and over during weeks of harrowing investigation. So many of the dead had lived alone. So many of them lived lives of anonymity. It was the one thing they had in common.

The investigators had expected the heat to claim those with previous medical problems or the bedridden. They expected it to kill people who lived on the hot-plate top floors of buildings, or people with no air-conditioning or access to cool spaces. Indeed, those people were disproportionately represented among the dead. But nobody had fathomed just how deadly it was to be friendless.

“We found, if you’re socially isolated, your risk for heat wave mortality goes up sevenfold,” Semenza told me later. This was a conservative estimate. The CDC surveys didn’t include individuals who had no relationships whatsoever, because Semenza’s team was not able to learn a thing about such people. So there were hundreds of invisible dead, forgotten soon after their corpses were hauled off in refrigerated trucks hired by the county’s medical examiner. In the end, the heat wave claimed more than seven hundred people. Semenza was haunted by the experience and had been looking for a solution to the epidemic of urban isolation ever since.