Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (40 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

I last saw Meyer in the spring of 2010. She was standing in the middle of the parking lot in front of the neocolonial facade of the U.S. post office in Mableton, insisting that this spot, right here, was the center of town. If you didn’t know about her plan, you might have thought Meyer was crazy. She was surveying what looked to me like the middle of nowhere.

Mableton, you may recall, showed up in Lawrence Frank’s urban-health studies as one of those towns that is so unwalkable that people get fatter just living there. The unincorporated community fifteen miles west of downtown Atlanta is the kind of place where you could drive for days and never quite feel that you had arrived anywhere. Tendrils of asphalt braid and curl through the semi-urban sprawl northeast of Atlanta’s Perimeter beltway, with cul-de-sacs and strip malls and business parks evenly scattered over the rolling terrain. If you circled the dying mall down on Veterans Memorial Highway—cruelly misnamed the Village at Mableton—or doubled back and headed up to the big-box power centers that cling to the East-West Connector, you would find yourself increasingly disoriented, and you would not have found anything you’d call a downtown—certainly not the view from the post office parking lot.

From where we stood, a lawn fell away past a looping access drive and a deep swale. Beyond that, cars and trucks sped along Floyd Road’s five wide lanes. Beyond more parking lots and lawn, we could see the clapboard plantation house built in 1843 by the Scottish settler and town founder Robert Mable. South of the old house, across another broad parking lot, was the Mable House Arts Center and beyond that, a new park-and-ride lot where hundreds of spaces sat entirely unoccupied on this, a weekday. The busiest place in sight was the twenty-bay RaceTrac gas station down at the intersection of Floyd and Clay roads.

Every destination in Mableton was an island, isolated by those formidable swaths of asphalt and grass. Everywhere we looked, parking space exceeded building footprints by at least three to one. You’d be crazy to walk from the post office to the library behind the gas station, or the shopping plaza beyond that, or even to the arts center right across Floyd Road. “That would be a death march,” Meyer said, referring to both the frying rays of the Georgia summer sun and Floyd Road itself, which has grown over the years into a commuter highway, speeding people between distant mega-schools, power centers, business parks, and dollar stores. But this was it, she said. This was the place that mattered. This is where Mableton would reinvent itself.

Meyer had spent years being perfectly content with the horizontal suburb. She and her husband built a house on a four-acre lot a few miles from the post office back in 1984, and they made the weekday freeway commute into Atlanta for years. But now that she had retired, given up her commute, and gotten involved in the Mableton Improvement Coalition (she was chairman of the board), Meyer was acutely aware that there is no

there

in Mableton. “There’s no center—no place for people to gather and have all the sorts of things that communities are

supposed

to have,” she said. She didn’t want anything radical. Just a village where she could park her car, walk around and do a few errands, and feel as though she were someplace.

Meyer could see the outlines of that place as she squinted out across the collage of asphalt and lawn. The two architects who stood with us could see it too.

“The town square could be right here,” offered Galina Tachieva, a partner at the urban planning firm Duany Plater-Zyberk (DPZ). She pulled off her bug-eye sunglasses and swept a hand across the scene. “And there could be a row of shops or live-work studios lining it. And this

disastrous

road needs to be slowed down so that old people and children can actually walk across it. We might add parking along the curbs, or split the road in half, like a zipper.”

That was a beginning. But why stop there? they said. Why not build some veranda-fronted two- or three-story buildings in the parking lots of the sickly plazas along Floyd Road? Why not push those buildings right up against the sidewalks like the streets of old towns everyone likes to visit? Why not turn the field just north of the post office—a farm owned by former Georgia governor Roy Barnes—into a village center with housing for seniors? Why not connect nearby roads so folks could actually walk places? It was a tremendous fantasy for a spring afternoon. It was also illegal.

Urgency and Imagination

Once upon a time, urban pioneers stood upon the untamed ground across North America and summoned up enough imagination to proclaim that towns, and maybe even cities, would rise from the wilderness on which they stood. It takes similar resolve to stand on the tarmac outside the Mableton post office—or any other spot on the suburban savannas that surround North American cities—and imagine anything like a town replacing the durable landscape of sprawl. But it is an idea that has grown steadily more urgent, and it is more than an aesthetic concern.

I have already outlined how this landscape can make people sicker, fatter, more frustrated, socially isolated, and broke. I have shown how it makes streets more dangerous. But this urban form also happens to deny a growing majority of people the life they actually want. In 2011 a survey by the National Association of Realtors found that six in ten Americans say they would rather live in a neighborhood that has a mix of houses, stores, and businesses within an easy walk than one that forced them to drive everywhere. But in places like Atlanta, only about 10 percent of homes can access such wonders.

The sprawl city is also facing a slow-moving crisis that is arguably just as dire as the foreclosure meltdown that singed American cities these past years. In 2009 the Atlanta Regional Commission issued a warning: by 2030, one out of every five residents in the Atlanta metro region would be over the age of sixty. And Atlanta’s suburbs are currently hell on the elderly. With everything so far away, many seniors can’t get anywhere on foot—leaving many in a homebound state that actually hastens the aging process. Those who can’t drive have a tough time getting services, and they are starved of the casual social encounters that keep people connected, strong, and healthy. In a sprawl future, millions of Atlantans will be stranded, alone in their homes or warehoused in retirement institutions, a fate even worse than the one currently experienced by kids and poor people in suburbs across the continent.

The commission made a call to action: it was time to figure out how to turn places like Mableton into communities that would work for people of all ages—even those who could not drive. Starting in 2009, they invited community members to meet with experts in health care, mobility, aging, transportation, accessibility, architecture, and planning in a brainstorming session known as a “charrette.”

Sprawl Repair

This is where Tachieva and her colleague Scott Ball came in. The two architects specialize in a kind of urban surgery that reverses the damage done by sprawl. Tachieva sees their task as nothing short of reversing a century of dispersal.

“Cities have been blown out of proportion, as though we were designing them for giants. What we were doing, of course, was designing for the scale of cars,” she said. “Now we are returning cities to a human scale. We are returning the balance of life to neighborhoods.”

Tachieva is driven by more than altruism. There’s money in the work she calls sprawl repair. The U.S. population is projected to grow by 120 million by 2050. Where will those people live? Downtowns and first-ring, streetcar-style suburbs will be able to accommodate only a fraction of the new demographic tidal wave. Most jobs have already moved out beyond city limits anyway. The masses, Tachieva says, will still need suburbia.

But these people won’t look at all like suburbia’s first few waves of migrants. Demographers project that most homebuyers in the next couple of decades will be empty-nest baby boomers or their single adult children. Only about one in ten buyers are likely to have children of their own. Those childless buyers won’t be in the market for traditional detached suburban homes. Neither will many new immigrants, who are simply not used to nor enthusiastic about endless auto commutes. Some analysts suggest that the United States already has enough large-lot single-family homes to meet demand right up to 2030.

“The party is over for sprawl,” Tachieva said. “The market is changing, and young people and old people are demanding something different. They want lively, sophisticated places where they can walk, and where they can still have freedom beyond the age of eighty.”

Tachieva literally wrote the book on the subject. Her how-to guide, the

Sprawl Repair Manual

, offers some wildly ambitious prescriptions: Business parks can be fixed by inserting streets and shops onto their tarmacs. Urban highways can be morphed into main streets by putting them on diets and slowing them down with narrower lanes, streetlights, and crosswalks. Disconnected tangles of cul-de-sac can be made walkable by strategic grafting of new roads and lanes between them. Huge, unaffordable McMansions can be divided into apartments. Gas stations can be humanized by wrapping their parking lots in new street-front businesses.

Parts of the

Sprawl Repair Manual

read like a blueprint for a fantasy urban universe; anything is possible on paper. But some of Tachieva’s prescriptions have already come to life in pockets across the continent.

One of the most striking retrofits is growing on the former site of a vast mall surrounded by parking on 104 acres in Lakewood, southwest of Denver. At the turn of the twentieth century, customers of the mall then known as Villa Italia had been sucked away by newer, bigger malls on the urban periphery. Some suggested turning the superblock site into a big-box power center. But what people in Lakewood really wanted was a downtown.

The city worked with a developer to turn the superblock into twenty-three smaller blocks, with streets woven into the network of the surrounding neighborhoods, combining shopping, offices, housing, and public space. Larger buildings and parking structures were “wrapped” with small street-fronting retail spaces, keeping streets active and slow, as Jan Gehl has counseled. The site is anchored not by its national retailers but by a block-size town green and a central plaza where people come and hang out without any need to shop. More than fifteen hundred people now live on the unfinished site in town houses, apartments above stores, lofts, and houses built up against the streets.

Megablock Redux

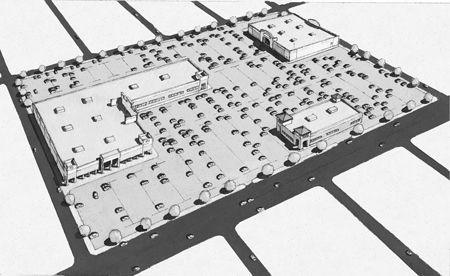

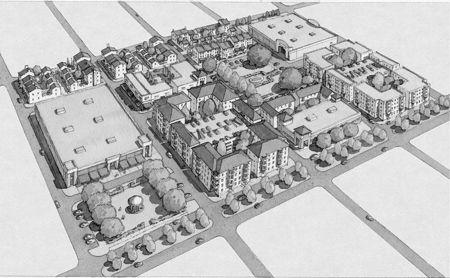

Sprawl-repair plans turn parking oceans (

top

) into walkable town centers (

above

) with parking stacked behind apartments and streets connected to surrounding neighborhoods.

(Copyright © Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company)

The important difference between a meaningful sprawl repair such as the Lakewood Towne Center and main street–imitating faux downtowns appearing across the continent is that the former achieves more than just the aesthetic feat of turning malls inside out. The true repair addresses the systemic problems of sprawl. By mixing shopping, services, and public space with housing, it allows people to escape the bonds of their seat belts and walk if they wish. It creates a critical mass of demand for transit, and comfortable places to wait for it. It links streets to surrounding networks, making walking easier and extending tendrils of easier living, good health, sociability, and connectivity. It offers truly public space—that is, owned and controlled by the local municipality, not the mall owner or developer. On the plaza at Lakewood you can loiter, stage a piggyback fight, or a demonstration, for that matter, without depending on the goodwill of the private security forces that have come to dominate public-private spaces from Disneyland to Midtown Manhattan. These mall retrofits are not quite the same as a downtown, and not quite as fine-grained and unpredictable as the old streetcar neighborhood, but they do infuse choice and freedom into the homogeneity of sprawl.