Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (42 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Mableton would not be a passing blur in a windshield. It would be a place for slowing down, for staying. Hundreds of people would get to live in or near a core that could offer them an easier, richer, more resilient existence. They would get what people in old downtowns and streetcar suburbs have enjoyed all along. By their very proximity, they would provide the body heat to support businesses, vibrant streets, and a commuter train station on the rail line that now cuts through town without stopping. And people like Meyer, who prefer their cars, would get a town center worth driving to.

By giving some people the choice of living close together and close to the necessities of life, everyone in Mableton would eventually come out ahead. That was the vision.

Neo-Suburban Dream

Mableton today

The Mableton people want

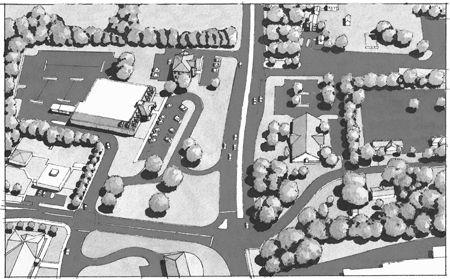

Mableton town center (

top

) is configured like a rest stop, with destinations dispersed amid seas of lawn and parking astride highwaylike Floyd Road. Residents have set out a vision (

above

) to turn the town center into a walkable village core with a mix of housing, retail, public buildings, and parks, with car parking tucked behind buildings and Floyd Road tamed into a boulevard.

(Copyright © Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company)

But the plan would have died in the elementary school classroom had it not been accompanied by new rules—a new operating system. So, after the people traced out their aspirations, Tachieva and Ball translated them into a new form-based code, a straightforward set of rules to guide the design of new developments in the area around Mableton. Meyer and her allies worked to convince Cobb County’s governing board of commissioners to take a chance on the new code. They were more than successful. The following year, that code was adopted for all of Cobb County. Rather than totally replacing the county’s old code, it now runs alongside it: property developers can choose which code they wish to have applied to their project applications.

The new Mableton won’t be built without investment from property developers. The form-based code contains some honey for them by making the building permit process easier, simpler, and more predictable. At the same time, Cobb County will fast-track projects that choose the new code. It will take years for a new generation of developments to repair Mableton, but at least the system is now stacked to favor the future that people actually want.

Changing the Game

As the people in Mableton realized, the battle to repair sprawl on a large scale means convincing developers that they can make money by building stuff they have avoided for decades.

To this end, Tachieva insists that form-based codes do not go far enough. Even when communities and decision makers agree that the old sprawl patterns are not sustainable, the dispersal system can rumble on like a runaway truck, propelled by the momentum of a century of rules, guidelines, and state-mandated community plans. Every level of government offers incentives for sprawl-style development and penalties for smart growth, sometimes without even knowing it.

The lingering incentives for sprawl are too numerous to name, but here are a few glaring examples:

First there is the “traffic impact exaction,” a standard fee that municipalities charge developers who create new density, based on the superficial assumption that density creates more automobile traffic and thus more costs. It backfires horribly because it actually punishes the kinds of mixed-use development that can support transit, and it spreads new development farther and farther across the landscape, creating even more traffic.

Then there is the U.S. government’s accelerated depreciation tax deduction, which gives developers a generous tax break for creating new buildings rather than renovating or reusing old ones. It effectively rewards Walmart for abandoning older stores and building in regional power centers far from the communities they first promised to serve.

Another misguided gift to sprawl is the home mortgage interest tax deduction. The United States is one of only a handful of countries in the world that gives individuals a tax break on interest for home mortgages. In practice, the deduction has given the biggest tax break to people who can afford to buy new homes on the suburban fringe rather than those who buy cheaper, modest homes in older neighborhoods. (Personal loans for renovations, for example, don’t get the deduction.) By encouraging homeowners to delay paying down big mortgages, it helped cause the foreclosure crisis. And it apparently does little to boost home ownership. In Canada, where there is no such tax break, the rate of home ownership is slightly higher than in the United States. By rewarding sprawl buyers, it passes massive new costs on to municipalities, which then have to build new schools, fire stations, and roads to service horizontal growth.

To top it off, governments have continued the decades-old practice of pouring tax dollars into highways and low-density infrastructure while spending a tiny fraction of that amount on urban rail and other transit service. For example, of the 18.4 cents per gallon the U.S. government took in gas taxes in 2012, only 2.86 cents went to public transit and almost all the rest was poured into highways. (Thus, as fuel costs and the recession drove more people than ever to transit, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA, actually consolidated bus routes and cut subway services.) Complicating matters, almost all major developments and road changes have to be approved by state governments, whose own regulations may have their origins back in the early years of dispersed city building.

“Sprawl was incentivized,” Tachieva says. “Now we want to get similar incentives for mixed-use and walkable places. We need to level the playing field and give an equal chance for efforts to improve the places we already have.”

She and other sprawl-repair activists are taking the lead by writing model sprawl-repair acts as unsolicited gifts for state governments. The acts enable states and municipalities to change infrastructure-funding rules, tax incentives, and permit requirements to make it just as easy to retrofit dead malls into dense, walkable, mixed-use town centers as it is to build big-box deserts. They allow fast-tracked permitting for sprawl repairs and tax incentives for the kinds of places that people actually love. (At the time of writing, the Commercial Center Revitalization Act, inspired by Tachieva’s work, was gradually making its way through the South Carolina state legislature.)

If all this sounds like a big fat bonus for property developers, well, it is. But the truth is, as long as we inhabit a capitalist system, the future of suburbia depends on them.

The vast majority of real estate developments in the United States are controlled by a handful of huge Wall Street–controlled real estate investment trusts. Wall Street traders are not interested in the complexity of urban life. They are interested in easily tradable commodities, explains Christopher Leinberger, the land-use strategist. Leinberger has found that in the last couple of decades, real estate has come to be sorted into a limited set of product types, all based on the segregated, drivable model set out by the modernists a lifetime ago. Retail development, for example, will either be a neighborhood center, a lifestyle center, or a big-box-anchored power center, product types that Wall Street financiers can quantify, approve, and exchange without ever actually visiting the building site or so much as talking to anyone from the community about what they actually want.

“Bank loan officers now specialize in just one of these types of real estate; bring them something different and they will generally show you the door,” writes Leinberger in

The Option of Urbanism

. Despite the apparent recklessness that led to the 2008 financial crisis, lenders generally recoil from complexity and risk, so their funding formulas have ended up reinforcing simplistic, separatist patterns of development. Mixed-use retrofits demand more care and attention, and a cognitive break for these developers. If you cannot offer them certainty and attractive returns, says Tachieva, then the vast drosscapes and dead malls left behind by sprawl’s horizontal charge are unlikely to be repaired for many years.

*

The Aesthetic Trap

One other force complicates sprawl repair. It lives in the way each of us perceives the relationship between architecture and the urban system. Every one of us carries an idea of what the ideal town is supposed to look like, but that idea is most often represented by a set of images in our head rather than by deep consideration of the complex systems that make the place function in a particular way. As Elizabeth Dunn discovered in her Harvard dorm studies, most people exaggerate the life-changing power of aesthetics and architectural details. We tend to judge the character and health of a place—and even its residents—by the very material used on building facades.

†

Most of us are drawn to and comforted by designs that remind us of pleasant times in the past or in our imagination. This is one reason why New Urbanist retrofits are frequently wrapped in neo-traditional packages. It’s a form of subversive marketing, as Ellen Dunham-Jones, coauthor of

Retrofitting Suburbia

, explained to me. New Urbanist designers and developers know that what they are selling is entirely unfamiliar for many people—mixed use, mixed income, density, and transit. So they use nostalgic, unthreatening forms to gently build acceptance for what are essentially progressive public goals. Form is the spoonful of sugar that helps the good medicine go down. Superficial but effective.

But this focus on aesthetics can blind us to crucial elements of design. This is what seems to have happened just down the road from Mableton, where the town of Smyrna demolished its moribund former core and built a hedonic landscape on the ruins. I wandered Smyrna’s new Market Village with the mayor, Max Bacon, in 2010. The main drag, Spring Street, was lined with faux-antebellum mansions, complete with white columns, expansive porches, and brick facades. There was a classical fountain at one end and a gazebo at the other, and beyond that, instead of Sleeping Beauty’s Castle, was the Romanesque facade of a new city hall, capped with a miniature tower.

The project’s architect, Mike Sizemore, was pleased to hear me compare Spring Street to Disney’s Main Street U.S.A. “The style was an attempt to tie Smyrna into a past that people wish they had, a past they aspire to,” he said. “The solid, tapered columns and the porches with their rocking chairs all speak of the elegance and stability of the Old South.”

Reinventing the Familiar

Like Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A., Smyrna’s Market Village was designed to remind people of an idealized past.

(Courtesy of Sizemore Group Architects)

The village, with its quaint restaurants, ice-cream parlor, art shops, and fitness center, was a huge hit when it opened in 2003. The apartments above the shops sold within months of being finished. So did the cottages nearby. Smyrna’s council members had risked their political necks, raising property taxes in order to help bankroll the project, but after the village opened, land values within a mile radius went through the roof, inflating the city’s tax revenue twentyfold. The city started raking in so much money that the city council cut the tax rate by 30 percent, making it near the lowest in the state. “It sounds like a Bernie Madoff scheme, but it’s true!” one councilor gushed.