Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (21 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

For financial shenanigan detection purposes, we recommend calculating DSI using the ending balance of inventory (rather than the average balance, as some companies and texts may advise). The ending balance provides more relevant data about future margin pressure, potential obsolescence, product demand, and so on.

Sometimes a company will stock up on inventory heading into a period of expected increased demand and rapid sales growth. While this may be a perfectly legitimate business strategy, companies use it as a common excuse to justify unwarranted inventory growth. When they are presented with this reasoning as an explanation for increased inventory, investors should determine whether the strategy had been planned before the inventory buildup, or whether the strategy was hatched as a defensive response to the inventory buildup. Investors should be skeptical if no mention of this growth strategy had previously been made.

Luckily, an alternative exists to test whether an inventory buildup might be justified by upcoming demand: simply compare the growth in the absolute level of inventory to the company’s expected revenue growth. If inventory growth far exceeds the expected sales growth, the inventory bulge is probably unwarranted and a concern for investors.

Coldwater Creek Finds Itself in Hot Water.

Consider the case of women’s clothing retailer Coldwater Creek Inc., whose inventory swelled in the July 2006 quarter. Management told investors not to fret about the higher inventory balance with several justifications, including the need to fill the shelves at the 60 new stores that had opened in the past year. A quick calculation of DSI (98 days versus 78 days the year before), however, revealed that the inventory growth had exceeded the recent growth of the business, a signal of diminished profits in future periods. Moreover, the year-over-year growth in the company’s inventory balance (67.2 percent) seemed completely unjustified when compared with management’s expectations for revenue growth in the second half of 2006 (24.3 percent).

Astute investors would have been completely unsurprised when the company reported miserable results at the end of 2006 and throughout 2007. Deeply discounted clothes filled Coldwater Creek stores (including many 90-percent-off racks) as the company struggled to move excess inventory. Coldwater Creek’s earnings disappointed Wall Street, and its stock price fell from above $30 per share at the beginning of the 2006 holiday season to below $10 heading into the 2007 holidays.

4. Failing to Record Expenses for Uncollectible Receivables and Devalued Investments

Recall the two general categories of assets discussed earlier in the chapter: assets created from costs that management expects to produce a future benefit (e.g., inventory, equipment, and prepaid insurance) and assets created from sales or investments that will be exchanged for an asset such as cash (e.g., receivables and investments). The first three sections of this chapter featured games that are played with the flow of the first category of assets to the Statement of Income, or, as we presented it, manipulating the two-step accounting dance. In this final section of the chapter, we focus on games played with the other category of assets. Specifically, we show how companies inflate earnings by failing to turn these assets into expenses when a clear loss in value has occurred.

Some lucky companies have customers that always pay their bills in full and hold only investments that never decline in value. Such companies are rare indeed. Most companies will have a certain number of deadbeat clients and the occasional clunker in their investment portfolio. Heck, even Warren Buffett strikes out from time to time.

When this happens, companies cannot just close their eyes and pray that all their receivables will eventually be collected. Accounting rules require that certain assets be regularly written down to their net realizable value (accountants’ lingo for the actual amount you expect to get paid). Accounts receivable should be written down each period by recording an estimated expense for likely bad debts. Similarly, lenders should record an expense (or loan loss) each quarter to account for the anticipated deadbeat borrowers. Additionally, investments that experience a permanent decline in value must be written down by recording an impairment expense. Failing to take any of these charges will result in overstated profits.

Failure to Adequately Reserve for Uncollectible Customer Receivables

Companies must routinely adjust their accounts receivable balance to reflect expected customer defaults. This entails recording an expense on the Statement of Income (“bad debts expense”) and a reduction of accounts receivable on the Balance Sheet (the “allowance for doubtful accounts,” which offsets gross receivables). Failing to record sufficient bad debts expense or inappropriately reversing past bad debts expense creates artificial profits.

Watch for a Decline in Bad Debts Expense.

Our friends at Vitesse Semiconductor must have conveniently forgotten what it means to accrue for expenses. In the last section, we saw that Vitesse failed to accrue any inventory obsolescence expense in 2003 after recording a $30.5 million charge the previous year. The company also decided to record just $1.9 million in bad debts expense after recording $14.3 million in the previous year. Tack on an additional reduction in an expense for estimated sales returns, and Vitesse accrued just $2.2 million in estimated expenses during 2003, after having recorded $49.9 million in such expenses during 2002. Had Vitesse accrued these expenses at the same percentage of revenue as in the previous year, its operating income would have been approximately $50 million lower. All these tricks at a company with only $156 million in revenue created a huge distortion for investors. So it should be no surprise that a board investigation in 2006 uncovered a laundry list of accounting problems, many of which involved improper accounting for revenue and receivables.

Warning:

When all reserve accruals are moving in the wrong direction (i.e., declining), head for the hills!

Watch for a Drop in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts.

Under normal business conditions, a company’s allowance for doubtful accounts will grow at a rate similar to that for gross accounts receivable. A sharp decline in the allowance, coupled with a rise in receivables, often signals that a company has failed to record enough bad debts expense, and therefore has overstated earnings. Such a decline apparently occurred at publisher Scholastic Corporation. Its accounts receivable balance jumped 5 percent in fiscal 2002, yet the allowance for doubtful accounts (ADA) declined by 11 percent. On a percentage basis (i.e., ADA as a percentage of gross receivables), ADA dropped to 20.4 percent of receivables in 2002 from 24.1 percent in 2001. Had Scholastic kept the allowance account at 24.1 percent, 2002 operating income would have been $11.3 million lower. Like Vitesse, Scholastic was taking down several other reserves as well, including its inventory obsolescence reserve, royalty advances reserve, and a reserve related to a recent acquisition. According to a CFRA study at the time, Scholastic’s operating income would have been about $28 million (15 percent) lower in 2002 without all of these reserve reductions.

Failure by Lenders to Adequately Reserve for Credit Losses

Financial institutions and other lenders must continually estimate the portion of the loans they make that they expect to never collect (called

credit losses

or

loan losses

). The mechanics of this accrual essentially mirror those that are used when reserving for uncollectible accounts receivable. The lender records an expense on the Statement of Income (called a “provision for credit losses” or “loan loss expense”) and a reduction in total loans receivable on the Balance Sheet (called “allowance for loan losses” or “loan loss reserve”), shown as an offset to gross loans.

Ideally, the total amount in the loan loss reserve should be enough to cover all loans that the bank believes are now or are likely to be in default based on conditions that exist at the date of the financial statements. The additions to reserves charged against income each year should be enough to maintain the reserves at the appropriate level. When management fails to reserve a sufficient amount for losses, however, profits will be overstated. This overstatement will eventually catch up to the company when the loans go bad, as the company will be forced to write off bad loans with insufficient reserves accrued.

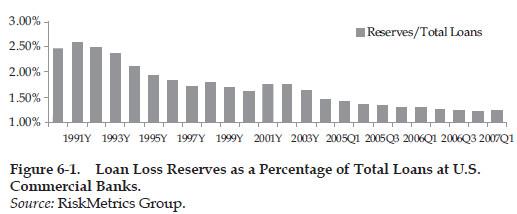

That’s precisely what happened on a global scale leading up to the credit crisis that began in 2007. According to a mid-2007 study by RiskMetrics, from 1990 through 2006, major U.S. commercial banks had consistently reduced their loan loss reserve levels, which inflated their profits but left the companies woefully under-reserved and exposed to deterioration in credit quality. As shown in Figure 6-1, loan loss reserves fell to just 1.21 percent of total loans—a historic low, and well below the 2.50 percent range in the early 1990s. This very optimistic view of the world that loans would almost never go bad strikes us as completely unrealistic. More likely, it provided companies with the ammunition to continuously inflate their profits. These paltry industrywide reserve levels in 2006 not only boosted earnings and left companies exposed to the coming credit crisis, but indeed actually helped to create the crisis itself.

Watch for a Drop in Loan Loss Reserves

. Heading into the painful real estate collapse of the late 2000s, many lenders failed to establish adequate reserves for bad loans and consequently hid their losses from investors. Lenders to the riskiest customers, the so-called subprime market, were especially exposed. Subprime borrowers often received substantial loans despite having poor credit histories, no income documentation, and plenty of debt. The subprime market eventually crashed when a large number of these bad borrowers defaulted on their payments.

As lenders began to see increases in borrower defaults and delinquencies, they should have increased their allowance reserves accordingly. However, these companies were hesitant to record the expenses necessary to increase their reserves (or even maintain them at the same level) because it would have meant showing lower earnings during what by all appearances seemed to be a vibrant bull market.

New Century Financial completely defied logic in late 2006 by

reducing

its allowance for loan losses in the face of higher delinquencies and increasing nonaccrual (bad) loans. In the September 2006 quarter, New Century shockingly lowered its loan loss reserve to $191 million (23.4 percent of bad loans) from $210 million (29.5 percent). Management probably understood that this action was inappropriate, as the company obfuscated its presentation of the loan loss reserve during the earnings release to make it seem as if the reserve had actually increased. (We explore such creative manipulation of important metrics in Part 4, “Key Metrics Shenanigans.”) Had the company kept its loan loss reserve at a similar percentage of nonaccrual loans as in the previous quarter, earnings in September 2006 would have been cut by a whopping 58 percent—to $0.47 from the $1.12 reported.

Investors who monitored New Century’s loan loss reserve had fair warning of the company’s impending demise. In early February 2007, one day before the scheduled release of its fourth-quarter results, the company announced a restatement of earnings for the first three quarters of 2006. The stock went into a free fall, and two months later New Century filed for bankruptcy. Lawsuits ensued, and the SEC charged senior management with securities fraud for misleading investors as the business was collapsing.

RED FLAG!

Loan loss reserves decline relative to bad (nonaccrual or nonperforming) loans.

Failure to Write Down Impaired Investments

Companies must also review their investment portfolio for clunkers. If an investment in a stock, bond, or other security experiences a sharp and permanent decline in value, the company must record an impairment expense. This principle especially pertains to certain industries, such as insurance and banks, for which investments represent a large portion of their assets.

When assets become permanently impaired, management cannot just keep reporting them at inflated values on the Balance Sheet and pretend that there has been no adverse impact on earnings. Rather, impairment charges must be recorded to reduce these assets to their appropriate fair value. Investors should watch for companies that fail to take impairment losses during market downturns, as occurred during the collapse of almost every asset class in the late 2000s and the resulting devastation of company investment portfolios.