Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (18 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Interestingly, the capital that Enron contributed to some of these joint ventures turned out to be nothing other than its own stock. In some cases, the partnerships themselves even held Enron stock among their investment holdings. As its stock price jumped over time, the value of the joint venture assets likewise increased, as did Enron’s own equity stake in these partnerships. This trick allowed Enron to recognize approximately $85 million in earnings as a result of nothing more than an increase in its own stock price during a fabulous bull market.

So Enron’s rapidly appreciating stock price became the “drug” that drove up the value of its partnership stakes and its income. In one period alone, for example, Enron generated a whopping $126 million from a joint venture. Curiously, when the stock began its rapid descent, Enron must have developed a severe case of amnesia and simply forgotten that the resulting $90 million loss should also be reported to shareholders. Instead, Enron conveniently announced that the results remained “unconsolidated” and, of course, not included on the Statement of Income. So, by Enron’s rules, on the very same investment vehicle, gains get consolidated and losses are hidden from investors’ view. In other words, for Enron it was— heads I win, tails I still win! Well, we all know how that sad story ended.

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities

• Boosting income using one-time events

• Turning proceeds from the sale of a business into a recurring revenue stream

• Commingling future product sales with buying a business

• Shifting normal operating expenses below the line

• Routinely recording restructuring charges

• Shifting losses to discontinued operations

• Including proceeds received from selling a subsidiary as revenue

• Operating income growing much faster than sales

• Suspicious or frequent use of joint ventures when unwarranted

• Misclassification of income from joint ventures

• Using discretion regarding Balance Sheet classification to boost operating income

Looking Ahead

Now we can catch our collective breaths for a moment and reflect, as we have reached an important stage in the book. The end of Chapter 5 marks the completion of the third of the three chapters that focus on techniques that inflate current-period profits by recognizing too much revenue or other income, such as one-time gains on events or from questionable management assessments.

The next two chapters complete the lesson on inflating profits, but they focus on reporting too few expenses. Chapter 6 (“Shenanigan No. 4: Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period”) shows how expenses can be hidden on the Balance Sheet and, as a result, shifted to a later period. Chapter 7 (“Shenanigan No. 5: Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses”) describes gimmicks for keeping expenses out of investors’ view today and, in some cases, forever.

6 – Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 4: Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period

The Texas two-step is a vibrant country-and-western dance made popular by the 1970s film

Urban Cowboy

. Once a simple barn dance, the version of the two-step that is danced today has evolved to include moves borrowed from the foxtrot and swing. Dancers whirl around the floor and routinely swap partners, providing great entertainment for their fellow dancers and for observers as well.

Companies account for their costs and expenditures in a similar two-step accounting dance. Step 1 occurs at the time of the expenditure—when the cost has been paid, but the related benefit has not yet been received. At Step 1, the expenditure represents a

future benefit

to the company, and is therefore recorded on the Balance Sheet as an asset. Step 2 happens when the benefit is received. At this point, the cost should be shifted from the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Income and recorded as an expense.

This accounting two-step is danced at different tempos, depending on whether the cost is related to a benefit with a long- or a short-term horizon. Costs with a long-term benefit sometimes require a slower dance in which the cost remains on the Balance Sheet and is recorded as an expense gradually (e.g., equipment with a useful life of 20 years). Costs that provide a short-term benefit require a fast-paced dance in which the two steps happen virtually simultaneously. Such costs spend no time on the Balance Sheet, but instead are recorded as expenses (e.g., most typical operating expenses, such as salaries and electricity costs).

Companies can exert their own influence over the speed at which they dance the two-step, and this discretion can have significant implications for earnings. Diligent investors should assess whether management is improperly keeping costs frozen at Step 1 on the Balance Sheet, instead of continuing the dance and moving them to Step 2 as expenses on the Statement of Income. Chapter 6 shows four techniques that management uses to exploit the two-step process by improperly keeping costs on the Balance Sheet, thereby preventing them from reducing earnings until a later period.

Techniques to Shift Current Expenses to a Later Period

1. Improperly Capitalizing Normal Operating Expenses

2. Amortizing Costs Too Slowly

3. Failing to Write Down Assets with Impaired Value

4. Failing to Record Expenses for Uncollectible Receivables and Devalued Investments

1. Improperly Capitalizing Normal Operating Expenses

The first section of this chapter focuses on a very common abuse of the two-step process: management’s taking only one step when two are required. In other words, management improperly records costs on the Balance Sheet as an asset (or “capitalizes” the costs), instead of expensing them immediately.

Accounting Capsule: Assets and Expenses

For this discussion, it is helpful to think of assets as falling into one of two categories: (1) those that are expected to produce a future benefit (e.g., inventory, equipment, and prepaid insurance) and (2) those that are ultimately expected to be exchanged for another asset such as cash (e.g., receivables and investments). Assets that are expected to provide a future benefit are actually close cousins of expenses: they both represent costs incurred to grow a business. The key distinction between these assets and expenses is timing.

For example, assume that a company purchases a two-year insurance policy. At its inception, the entire amount represents a future benefit and would be classified as an asset. After one year’s benefit has been received, half the costs would be shown as an asset and the other half as an expense. After the second year, none of the costs would remain as an asset, and the remaining half still in the asset group would be expensed.

Improperly Capitalizing Routine Operating Expenses

At the height of the 1990s dot-com boom, telecom services behemoth WorldCom Inc. entered into many long-term network access arrangements to lease line costs from other telecommunication carriers. These costs represented fees that WorldCom paid for the right to use other companies’ telecommunication networks. At first, WorldCom properly accounted for these costs as an expense on its Statement of Income.

With the technology meltdown beginning in 2000, WorldCom’s revenue growth began to slow, and investors started paying more attention to the company’s large operating expenses. And line costs were, by far, WorldCom’s largest operating expense. The company became concerned about its ability to meet the expectations of Wall Street analysts. Disappointment would surely devastate investors. So WorldCom decided to use a simple trick to keep earnings afloat. In mid-2000, it began concealing some line costs through a sudden, and very significant, change in its accounting. (Red flag!)

Rather than recording all of these costs as expenses, WorldCom capitalized large portions of them as assets on the Balance Sheet. The company did this to the tune of billions of dollars, which had the impact of grossly understating expenses and overstating profits from mid-2000 to early 2002.

Warning Signs of Improper Capitalization of Line Costs.

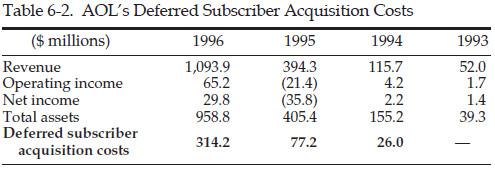

When WorldCom began capitalizing billions in line costs, it clearly continued paying the money out, although the Statement of Income reported fewer expenses. As pointed out in Chapter 1, a careful reading of the Statement of Cash Flows would have flashed a bright light on deteriorating free cash flow (that is, cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures). Table 6-1 shows how free cash flow went from a

positive $2.3 billion

in 1999 (the year before capitalizing the line costs) to a

negative $3.8 billion

(an astounding $6.1 billion deterioration). Investors should have seen this trend as a sign of trouble.

In particular, WorldCom’s large increase in capital spending should have raised questions. It belied WorldCom’s own guidance (given at the beginning of the year) for relatively flat capital expenditures, and it came at a time when technology spending, in general, was collapsing. Indeed, this reported increase in capital spending was fiction; in reality, it was largely the result of WorldCom’s changing its accounting practices to shift normal operating costs (i.e., line costs) to the Balance Sheet to inflate profits. Diligent investors should have spotted the 32 percent jump (from $8.716 to $11.484 billion) in capital expenditures and questioned why this spending made sense during a technology slowdown in which the company’s operating cash flow had been sliced by 30 percent. Flagging such a massive increase in spending would prove to be an important first step in sniffing out one of the biggest accounting frauds in history.

Warning Signs of Improperly Capitalizing Normal Operating Expenses

• Unwarranted improvement in profit margins and a large jump in certain assets

• A big unexpected decline in free cash flow, with an equally big drop in cash flow from operations

• Unexpected increases in capital expenditures that belie the company’s original guidance and market conditions

Watch for Improper Capitalization of Marketing and Solicitation Costs.

Marketing and solicitation costs are other examples of normal operating expenses that produce short-term benefits. Most companies spend money to advertise their products or services. Accounting guidelines normally require that companies expense these payments immediately as normal recurring short-term operating costs. However, certain companies aggressively capitalize these costs and spread them out over several periods. Consider Internet pioneer AOL and its accounting treatment of solicitation costs during its critical mid-1990s growth years.

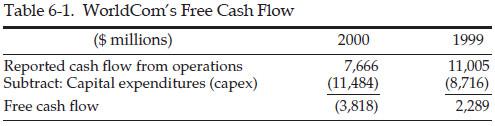

Until 1994, AOL treated its solicitation costs for new customers as an expense, called “deferred subscriber acquisition costs” (DSAC). However, in 1994, AOL started recording these costs as assets on its Balance Sheet. As shown in Table 6-2, AOL initially capitalized $26 million (representing 22 percent of sales and 17 percent of total assets) and then amortized those costs over the next 12 months.

Notice the dramatic increase in the DSAC balance over the next few years. By June 1996, DSAC on the Balance Sheet had ballooned to $314 million, or 33 percent of total assets and 61 percent of shareholders’ equity. Had these costs been expensed as incurred, AOL’s 1995 pretax loss would have been approximately $98 million instead of $21 million (including the write-off of DSAC that existed as of the end of fiscal year 1994), and AOL’s 1996 pretax income of $62 million would have been

transformed to a loss of $175 million.

On a quarterly basis, the effect of capitalizing DSAC was that AOL reported profits for six of the eight quarters in fiscal years 1995–1996, rather than reporting losses for each period.