Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (19 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Investors should have been alarmed when they reviewed these numbers for several reasons, including (1) the company made the initial

change from expensing

to the much more aggressive capitalizing, (2) the

enormous growth

in the unamortized DSAC represented a material underreporting of expenses and over-reporting of profits during these three years, and (3) AOL merely shifted expenses from current to future periods, and those costs would

materially dampen expected earnings in those future periods

.

AOL naturally tried to justify its accounting choice, asserting that it fell under an exception provided in accounting rule SOP 93–7. To qualify for the exception and be permitted to capitalize solicitation costs, a company would have to show persuasive evidence that the advertising would result in future benefits similar to the effects of the company’s prior direct-response advertising activities.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) disagreed with AOL’s treatment, stating that the company had failed to meet the essential requirements of SOP 93–7 because

the unstable business environment precluded reliable forecasts of future net revenues.

Investors actually needed no basic understanding of this cryptic accounting rule to realize that something smelled funny. AOL’s change to a more aggressive accounting policy and the sheer magnitude of that policy’s impact on earnings should have been more than enough to give astute investors indigestion.

Watch for Changes in Policy from Expensing Costs to Capitalizing Them.

Like AOL, Dallas-based telecom company Excel Communications changed from expensing to capitalizing regular operating costs at a pivotal time in its history—right before it registered with the SEC to become a public company in early 1996.

To ensure a successful initial public offering (IPO), the company apparently felt that it needed to dress up its rather modest earnings. Not a problem. It decided to change its accounting related to sales commissions. Until 1995, Excel had expensed these marketing costs immediately. Beginning in 1995, it capitalized them and then amortized them over a 12-month period. The immediate impact on profits was enormous. In 1995, earnings almost tripled, to $44.4 million (or 46 cents per share) from $15.9 million (or 18 cents per share) a year earlier. The aggressive accounting inflated profits by $22.7 million (or 51 percent of the 1995 earnings). Stated differently,

simply by changing to a more aggressive accounting policy, Excel artificially boosted its profits by 105 percent

.

EXCEL COMMUNICATION FOOTNOTE: REGISTRATION FOR IPO, CHANGING TO CAPITALIZING COSTS

The Company has adopted an accounting convention of amortizing capitalized subscriber acquisition costs to expense over a period of 12 months in order to better match those costs with the revenues from subscribers’ long distance usage during the first 12 months of service to such subscribers. Marketing services costs, as reflected in the Company’s Consolidated Financial Statements, include the effect of the capitalization of the portion of commissions paid for the acquisition of new subscribers during a period, as well as the effect of the current period amortization of amounts capitalized in the current and prior periods. The net effect of capitalizing and amortizing a portion of commissions expense was a reduction in marketing services costs.

Watch for Earnings Boosts After Adopting New Accounting Rules

. Occasionally, the decision to begin capitalizing operating costs comes not from a management whim but from compliance with a new accounting rule promulgated by the standard setters. While criticism of management for making such a change would clearly be unfair and unjustified, investors should recognize that any improvement in profit resulting from the change would be ephemeral and unrelated to operational success. For example, Lucent (now part of Alcatel) obtained a nice earnings boost as a result of beginning to capitalize internal-use software costs, mandated by a new accounting rule.

Tip:

Regardless of the legitimacy of an accounting change, investors must strive to understand the impact that this change had on earnings growth. Simply put:

any growth related to the change will not recur. In

order to be maintained, the growth must be replaced with improved operational performance.

Be Wary of Unusual Asset Accounts on the Balance Sheet.

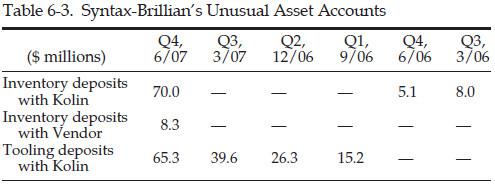

In the year before its bankruptcy and fraud investigation, our friends at HDTV maker Syntax-Brillian Corp. began reporting curious new asset accounts on the Balance Sheet called “tooling” and “inventory” deposits. The company provided minimal, and confusing, details about these assets, stating that they represented deposits to the company’s primary supplier of inventory (Kolin), according to reports by RiskMetrics Group in 2007. Oddly, both accounts dwarfed the total amount of inventory on the company’s Balance Sheet. Moreover, not only was Kolin Syntax-Brillian’s largest supplier, but it also was a related party, owning over 10 percent of the company’s stock and participating in joint ventures with the company.

Investors had reason to be skeptical about these new asset accounts, not only because of their unusual and related-party nature, but also because the balances were increasing very rapidly. As shown in Table 6-3, Syntax-Brillian reported a startling $70.0 million in “inventory deposits with Kolin” at June 2007, after having no such deposits in the preceding three quarters. Similarly, “tooling deposits with Kolin” were nonexistent in June 2006, but grew consistently over the next year, reaching $65.3 million at June 2007. A surge in any unusual asset accounts like these, particularly ones that involve a related party, should send investors running for the exits.

Warning Sign

: A new or unusual asset account (particularly one that is increasing rapidly) may signal improper capitalization.

Capitalizing Permissible Items, but in Too Great an Amount

Accounting guidelines permit companies to capitalize some operating costs, but only to a certain extent or if certain specific conditions can be met. We will call these costs

hybrids

—that is, the costs are recorded partially as an expense and partially as an asset.

Capitalizing Software Development Costs.

One operating cost that commonly finds its way to the Balance Sheet, particularly at technology companies, is the cost incurred to develop software-based products. Early-stage research and development costs for software would typically be expensed. Later-stage costs (those incurred once a project reaches “technological feasibility”) would typically be capitalized. Investors should be alert for companies that capitalize a disproportionately large amount of their software costs or that change accounting policies and begin to capitalize costs, particularly if those costs are out of line with industry practices.

Watch for Different Capitalization Policies within the Same Industry

. Companies within the same industry may apply the rules of capitalization in different ways. Since “technological feasibility” can be defined differently across industry players, similar companies may wind up with different levels of capitalized costs and therefore different profitability trends. The sooner a company decides that technological feasibility has been achieved, the sooner it can begin capitalizing costs and no longer charging them on the Statement of Income.

The entertainment software industry provides an excellent example of different treatment among similar companies. A 2005 study by the Center for Financial Research and Analysis (CFRA) on major entertainment software companies showed a disparity surrounding the capitalization of software development and royalty costs. In the June 2005 quarter, THQ Inc. led its peers with $2.58 in capitalized costs per share. Electronic Arts Inc., at the other end of the spectrum, had only $0.38. The disparity in capitalized costs was the result of different accounting interpretations. Electronic Arts conservatively expensed all software development costs, believing that technological feasibility arrives only when a software project is basically complete (an assessment that hurts earnings now, but helps them later). THQ, on the other hand, believed that technological feasibility was established much earlier (an assessment that helps earnings now, but hurts them later).

Watch for an Accelerating Rate of Software Capitalization.

Affiliated Computer Services Inc. (ACS), the Dallas-based outsourcing services provider, capitalized $44 million of software costs during 2003, representing 21 percent of total capital expenditures (sometimes called “capex”). This amount represented quite a jump from the $15.8 million (11 percent of capex) capitalized in 2002 and the $7.7 million (8 percent) in 2001. An accelerating rate of software capitalization is often a red flag that earnings benefited from keeping more costs on the Balance Sheet.

Improper Capitalization of Costs Also Inflates Operating Cash Flow

. While normal operating costs are reflected as an operating cash outflow, capitalized costs would be presented as capital expenditures in the Investing section of the Statement of Cash Flows. By capitalizing normal operating costs, companies inflate not only earnings, but also operating cash flow. We present this topic in Chapter 11, “CF Shenanigan No. 2: Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section.”

2. Amortizing Costs Too Slowly

Okay, put those dancing shoes back on as we get ready for the second step in our two-step accounting dance. Now that we have completed step 1, we have those costs capitalized, but the related benefit has yet to be received. Step 2 involves recording those costs as expenses, shifting them from the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Income.

The nature of a cost and the timing of its related benefit dictate the length of time that this cost remains on the Balance Sheet. For example, expenditures to purchase or manufacture inventory remain on the Balance Sheet until the inventory is sold and revenue recorded. On the other hand, expenditures to purchase equipment or a manufacturing facility provide a much longer-term benefit. These assets remain on the Balance Sheet for the duration of their useful lives, over which they gradually become expenses through depreciation or amortization.

Investors should raise concerns if costs remain as assets for too long, as evidenced by an unusually long amortization horizon. Additionally, if management decides to lengthen the amortization period, that should raise a loud warning signal.

Be Alert for Boosts to Income by Stretching Out the Amortization Period

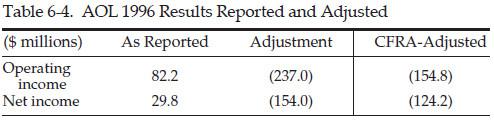

. Remember how our friends at AOL were spending a boatload of money to solicit new clients (as seen in Table 6-1)? We discussed the 1994 change in accounting to an aggressive capitalization of advertising costs and the decision to spread those costs over the next 12-month period. This aggressive capitalization completely misled investors, who believed that the company had been profitable, although in reality it was hemorrhaging cash and sustaining real economic losses.

Unfortunately for investors, the story did not end with that one trick. Beginning on July 1, 1995, AOL doubled the amortization period for these exploding marketing costs from 12 to 24 months. Extending the amortization period meant that the costs remained on the Balance Sheet much longer and reduced expenses with only half the impact each period. That change alone inflated profits by $48.1 million (to a

reported profit of $29.8 million from a loss of $18.3 million

). This creative accounting approach helped hide AOL’s huge losses from investors.