Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (36 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Tyco and WorldCom seemed to adhere to the “Shop ‘Til You Drop” mantra quite literally; however, they were buying entire businesses, and their holiday season ran all year long for many years. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, both companies went on lavish shopping sprees, acquiring business after business in order to fuel impressive performance. Organic growth at Tyco and WorldCom was much weaker than investors realized, though, as they hid their problems by acquiring oodles of companies and futzing with the accounting to show impressive results. They shopped and shopped—until the exposure of their massive accounting frauds caused them to drop like a ton of bricks.

Throughout their shopping sprees, both companies satiated investors and quashed red flags by consistently reporting strong cash flow from operations. However, in reality, this cash flow was not a sign of operational strength at all. Rather, it came mainly from a liberal use of Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 3: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals.

In this chapter, we will discuss three techniques by which Tyco, WorldCom, and other such companies use acquisitions and disposals to enhance and flatter cash flow from operations (CFFO).

Techniques to Inflate Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

1. Inheriting Operating Inflows in a Normal Business Acquisition

2. Acquiring Contracts or Customers Rather Than Developing Them Internally

3. Boosting CFFO by Creatively Structuring the Sale of a Business

1. Inheriting Operating Inflows in a Normal Business Acquisition

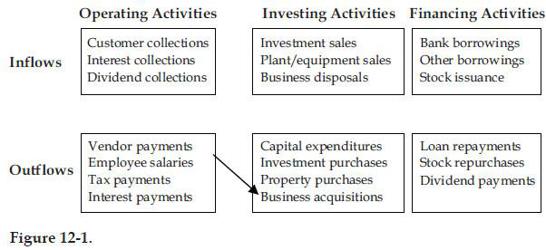

The cash flow shifting tricks in this chapter have many similarities to the ones we discussed in the previous chapter; they represent shifts between the Operating and the Investing sections. However, in this chapter, we focus solely on shifts that are related specifically to acquisitions and disposals. The first two techniques in this chapter involve shifting Operating cash outflows to the Investing section, as shown in Figure 12-1.

Rabidly acquisitive companies such as Tyco and WorldCom routinely reported impressive CFFO quarter after quarter. Faced with the opacity that is inherent whenever multiple sets of financial statements are suddenly combined, investors in these companies began to rely more heavily on CFFO generation as a sign of business strength and earnings quality. Unfortunately, heavy reliance on CFFO for acquisitive companies is ill advised because of a deep, dark secret that companies don’t want investors to know.

This secret concerns an accounting quirk (read loophole) that enables acquisitive companies to show strong CFFO every quarter

simply because they are acquiring other businesses

. In other words, the mere act of acquiring a company provides a benefit to CFFO. How can this be true? Well, it’s a peculiar side effect from the accounting rules that segregate cash flows into three sections. The quirk is actually quite simple and easy to understand.

Imagine you are a company that is getting ready to make a business acquisition. When you pay for the acquisition, you do so without affecting CFFO. If you buy the company with cash, the payment is recorded as an

Investing outflow

. If you offer stock instead, there is, of course, no cash outflow.

As soon as you gain control of the company, all of the ins and outs of the acquired business become a part of the combined company’s operations. For example, when the newly acquired company makes a sale, you naturally record that on your Statement of Income as revenue. Similarly, when the newly acquired company collects cash from a customer, you record that collection on your Statement of Cash Flows as an Operating inflow. Think about the cash flow implications of this situation. For one, you were able to generate a new cash flow stream (the acquired business) without any initial CFFO outflow. In contrast, companies that seek to grow their business

organically

would generally first incur CFFO outflows in order to build the new business.

Additionally, now that you inherited the receivables and inventory of the acquired business, you can generate an unsustainable CFFO benefit by rapidly liquidating these assets (that is, by collecting the receivables and selling the inventory). Normally, accounts receivable result from past cash expenditures (e.g., cash paid to purchase or manufacture the inventory sold). In other words, a cash inflow from collecting a receivable comes only after you have had a cash outflow to generate that receivable. When you acquire a company, however, and inherit its accounts receivable, the cash outflows involved in generating those receivables were recorded on the acquired company’s books prior to the acquisition. This means that when you collect those receivables, you will be receiving an

Operating

cash inflow without ever having recorded a corresponding

Operating

cash outflow. The same is true with inventory. The proceeds received from selling inventory inherited in an acquisition will be recorded as an Operating inflow even though no Operating outflow ever occurred.

Think of it this way: cash spent to purchase inventory and other costs related to the sale occurred before the acquisition, and when you close on the deal, you obviously must pay the seller for inventory, receivables, and so on, but those outflows are reflected in the Investing section. Then, after the deal closes, you collect all that delicious cash from customers and show it as inflows in the Operating section. By liquidating and not replenishing these assets (e.g., keeping the acquired business’s inventories at a lower level), you can show an unsustainable benefit to cash flow. Brilliant! In an acquisition context, cash outflows never hit the Operating section, yet all the inflows do.

To be fair, when companies inherit working capital liabilities (like accounts payable), then the acquirer will be on the hook for paying off the seller’s vendors and the cash paid will be an Operating cash outflow. However, most acquisitions involve companies that

have positive net working capital

(more receivables and inventory than accounts payable).

Accounting Capsule: The Impact of Acquisition Accounting on CFFO

A quirk in the accounting rules gives many companies a benefit to CFFO just for making an acquisition. A company that is growing organically will incur CFFO outflows (payments for creating and marketing products) in order to create CFFO inflows (receipts from customers). However, a company that is growing by acquiring other businesses generates growth without the stigma of those initial CFFO outflows.

To understand why, realize that cash spent to acquire another business runs through the Investing section of the Statement of Cash Flows (SCF) (of course, stock issued for an acquisition does not impact the SCF at all). As a result, when buying another business, companies inherit a brand new stream of cash flows without having to incur a CFFO outflow. Moreover, by liquidating the working capital of the acquired business, a company can provide itself with an unsustainable CFFO boost. These accounting nuances are why companies that grow through acquisitions often appear to have stronger CFFO than companies that grow organically.

It is important to realize that because this CFFO boost is considered perfectly permissible, even the most honest companies will benefit from inflated CFFO after making an acquisition. Moreover, this boost may cause “quality of earnings” measures (such as CFFO minus net income) to improve, particularly if a company does not engage in any Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans at the time of the acquisition.

Serial Acquirers Receive This CFFO Boost Repeatedly

So far, we have established that by their very nature, acquisitions serve to boost CFFO. Consider the impact at companies that make numerous acquisitions every year, serial acquirers like our friends at Tyco and WorldCom. Many investors criticize serial acquirers for being able to produce revenue and earnings growth only inorganically by “rolling up” acquisitions.

These “roll-ups” often reject this criticism and point to their CFFO as proof that they are running the acquired businesses well and exploiting synergies. Many investors believe this hype because they fail to understand the lesson that you just learned: stronger reported CFFO is merely an accounting side effect from acquiring numerous companies each year. Don’t misunderstand; we love companies that generate strong operating cash flows. What we don’t love are companies that make numerous acquisitions of mediocre companies and brag to investors about the strength of their underlying business, pointing to the exploding CFFO. They know the real story: the cash flow boost had virtually nothing to do with the performance of their business. They took advantage of the loopholes in acquisition accounting rules.

Putting the “Con” in Conglomerate

For some companies, these pure boosts to cash flow are just not enough. They want to squeeze even more juice out of these acquisitions. Consider the following scenario, based on allegations in legal proceedings of Tyco’s behavior during the acquisition process.

Imagine that you work in the accounting department of a company that just announced that it was being bought by a serial acquirer. The acquisition has not officially happened yet, but it is a friendly takeover with lucrative terms, and the deal is likely to close before the end of the month. The new owners want to start coordinating operations.

In walks one of the finance executives from the acquirer. He calls a meeting with the team and discusses some logistics that he says will help the transition go more smoothly.

He points to a pile of checks—payments from customers that you had planned to deposit later that day. “You see all those checks? I know you normally deposit them at the end of the day, but let’s hold off on that for now. Put them in this drawer, and we’ll deposit them in a few weeks. And let’s call up our biggest customers and tell them that they can hold off on paying us for a few weeks. I know that sounds odd, but this will score us some points and ensure that they stay loyal through the transition.

“And you see that pile of bills? I know you normally wait until the deadline approaches to pay them; however, let’s pay them down ASAP. In fact, see if you can prepay any vendors or suppliers—I’m sure those folks would be willing to take our money and perhaps even give us a discount. We certainly have enough cash in the bank; let’s put it to good use.”

The day after the acquisition closes, the executive returns. “Now that we are one company, it’s time to go back to normal business procedure. Deposit those checks immediately and start collecting from customers. And stop paying those bills early—let’s wait until we get closer to the deadline.”

Think about the cash flow implications of this scenario. The target company’s CFFO was abnormally low in the weeks leading up to the acquisition as a result of abandoning collection efforts and paying down bills rapidly. However, once the acquisition closed, there were an unusually large number of receivables to collect and an unusually small number of bills to pay. This causes CFFO for your division to be abnormally high in the period immediately after the acquisition.

The finance executive had a trick up his sleeve. His reasons for abandoning collection efforts and prepaying vendors had little to do with engendering goodwill. He concocted this scheme in order to boost the CFFO of the combined company in the first quarter after the acquisition. Granted, the effect of this benefit would be short-lived; however, the executive knew that the scheme could continue as long as the company kept rolling up more and more acquisitions each quarter.

Tyco: The Mother of All Roll-Ups

This scenario is similar to allegations of what happened behind the scenes when Tyco made its acquisitions. And Tyco made a lot of acquisitions. From 1999 to 2002, Tyco bought more than 700 companies (that’s not a typo) for a total of approximately $29 billion. Some of these acquisitions were large companies; however, most of the businesses acquired were small enough that Tyco considered them “immaterial” and chose to disclose nothing at all about them. Imagine the impact that this game could have with 700 companies worth a combined $29 billion! It should come as no surprise, then, that Tyco was able to generate strong CFFO over these years, as shown in Table 12-1. But it certainly was not from a booming business!