Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (16 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Consider the structure of a November 2006 deal between semiconductor giant Intel Corp. and fellow chip manufacturer Marvell Technology Group. Intel agreed to sell certain assets of its communications and application business to Marvell. At the same time, Marvell agreed to purchase a minimum number of wafers from Intel over the next two years. A careful reading of Marvell’s description of the transaction reveals something odd: Marvell agreed to purchase these wafers from Intel at

inflated

prices. (Interestingly, Intel did not disclose this, perhaps considering the amount to be insignificant.) Why would Marvell agree to overpay for this inventory?

MARVELL’S 10-Q DISCUSSION OF ITS TRANSACTION WITH INTEL

In conjunction with the acquisition of the ICAP Business, the Company entered into a supply agreement with Intel. The supply agreement obligates the Company to purchase certain finished product and sorted wafers at a contracted price from Intel for a contracted period of time. The contracted period of time can differ between finished products and sorted wafers.

Intel’s pricing to the Company was greater than comparable prices available to the Company in the market in almost all cases.

In accordance with purchase accounting, the Company recorded a liability at contract signing representing the difference between Intel prices and comparable market prices for those products for which the Company had a contractual obligation. [Italics added for emphasis.]

Tip:

Be sure to always review both parties’ disclosures on the sale of businesses to best grasp the true economics of the transactions.

Marvell certainly would not have agreed to pay an inflated price for purchases from Intel unless it was receiving something of equal value in return. Remember that Marvell and Intel negotiated the asset sale and the supply agreement concurrently. To understand the true economics of this arrangement, we must analyze both elements of the transaction together.

Economically, it would make sense for the total cash paid by Marvell for both the business and the future products to correspond with the value that Marvell was receiving from both the business acquired and the products that were later purchased. It follows, then, that if Marvell overpaid for the products, it must have underpaid for the business. In other words, Intel probably received less cash up front from the sale of the business in exchange for more cash later in the form of revenue from the sale of product. This certainly works out well for Intel, as a recurring revenue stream impresses investors far more than cash received from the sale of a business. Let’s wade into the numbers to understand exactly how this shenanigan works.

Mechanics of the Intel-Marvell Transaction.

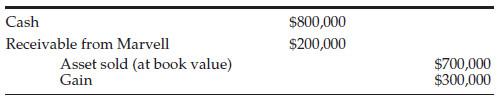

Using hypothetical numbers, let’s assume that the value of the business is $1,000,000 and that the structure of the deal involves Marvell paying Intel as follows: $800,000 up front and the remaining $200,000 later as the inflated price of products to be purchased. Also, assume that the business sold by Intel had a book value of $700,000; the gain from the sale of the business would therefore be $300,000 (sale price less book value). The economics of the transaction suggest that Intel should record the sale of the business as follows:

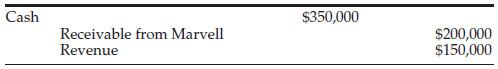

Notice that the total one-time gain is included immediately, even though $200,000 is still due from Marvell. Then, let us assume that, as originally agreed, Marvell later purchases $350,000 of products from Intel at the inflated prices so as to make Intel whole for having “discounted” the sales price of its business. The journal entry for the product sale by Intel would be the following:

Notice that the $350,000 received by Intel reflects both the $200,000 due from Marvell and the $150,000 in revenue that would be consistent with the normal selling price (not the inflated one). Had Intel recorded the transaction in this way, then investors would probably have understood the economics of the concurrent transactions more clearly: in the first period, Intel would have recorded a one-time gain of $300,000 from selling a business, and in a later period, it would have generated $150,000 in revenue from selling product to Marvell.

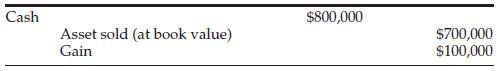

By commingling the current sale of a business and the future sale of products, Intel probably produced results that failed to capture the underlying economics by understating the one-time gain and inflating the product revenue. While Intel’s public disclosure does not provide specific details about the accounting entries surrounding this transaction, it seems likely that Intel first recorded

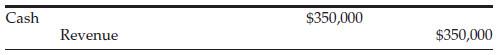

And then, when it received the inflated $350,000 for the subsequent product sale (which included $200,000 of gain held back), Intel probably recorded

The Net Result

. In this hypothetical example, Intel probably recorded $350,000 in revenue and a $100,000 one-time gain rather than $150,000 in revenue and a $300,000 one-time gain. Intel cleverly structured terms that legally permitted it to understate the one-time gain and overstate the more desirable stream of revenue. While some may claim that this ploy technically follows generally accepted accounting principles, in our judgment it fails to capture the underlying economics of the transaction.

Needless to say, Marvell’s financial reporting also benefited from paying less for the business and more for the products. (In Chapter 7, we return to Marvell and show how this arrangement provided the company with the opportunity to exert discretion over its earnings each quarter.)

Beware of Commingling the Sale of a Business with the Sale of Product.

Certainly the Intel-Marvell scheme is not a uniquely American phenomenon. On the other side of the Pacific, Japanese technology conglomerate Softbank also reported impressive results from its unusual method of accounting for the sale of a business. Specifically, it seems that rather than including the entire gain in the period of the sale, Softbank deferred some of the gain and used it to benefit future-period revenue and income.

In December 2005, Softbank sold its modem rental business and concurrently entered into an agreement to provide some services to the buyer. Softbank received a total of ¥85 billion, which it split between the sale and the service agreement, allocating ¥45 billion to the business sale and the remaining ¥40 billion to future revenue under the service agreement. By commingling the asset sale with later product sales, Softbank, like Intel, could report a smaller onetime gain and a larger stream of product revenue. As a result, investors might have been tricked into believing that Softbank’s sales were growing faster than the underlying economic reality. (We will return to discuss Softbank in Chapter 12 on Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 3.)

Warning Sign:

Commingling future product sales with buying a business.

The second section of this chapter illustrates the techniques that management may use to shift income or losses around so as to obfuscate any deterioration in a company’s operating profits.

2. Boosting Income through Misleading Classifications

When assessing a company’s business performance, it is of course important to analyze the earnings generated by the actual operations of the business (operating income). Gains and losses from interest, asset sales, investments, and other sources unrelated to actually operating the business (nonoperating income) are important to analyze as well; however, not in a review of a company’s operating performance. Some companies will misclassify income or losses and blur the line for investors in order to make operating income look better.

This section identifies three types of financial statement classifications that could inflate operating (above-the-line) income:

(1)

shifting the “bad stuff” (i.e., normal operating expenses) out to the nonoperating section

(2)

shifting the “good stuff” (i.e., nonoperating or nonrecurring income) into the operating section

(3)

using questionable management decisions regarding Balance Sheet classification to help offload the bad stuff or upload the good stuff

Accounting Capsule: Above-the-Line and Below-the-Line Income

The Statement of Income can be divided into two broad sections: operating (often called

above-the-line

) and nonoperating or nonrecurring (often called

below-the-line

). Investors typically pay much more attention to the operating income in assessing a company’s health. So naturally, companies prefer to showcase strong recurring operating income. In so doing, they may improperly shift nonoperating income or gains to the operating section or, conversely, shift operating expenses or losses to the nonoperating section. This type of intraperiod shifting of income to benefit the above-the-line presentation, while having no impact on the “bottom line” net income, can create a very misleading picture for investors.

•

Above-the-line:

income from the core business (revenue minus operating expenses)

•

Below-the-line

: noncore or nonrecurring gains or losses

Shifting Normal Expenses Below the Line

The most common way to shift normal operating expenses below the line involves one-time write-offs of costs that would normally appear in the operating section. For example, a company taking a one-time charge to write off inventory or plant and equipment would effectively shift the related expenses (i.e., cost of goods sold or depreciation) out of the operating section into the nonoperating section and, as a result, push up operating income.