Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (15 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Accounting Capsule: Revenue Recognition for Principals versus Agents

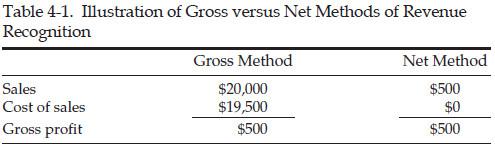

Principals recognize sales revenue at the gross amount of the transaction (i.e., the cost of the product plus the markup). In contrast, agents simply recognize revenue at the net amount (i.e., the agent’s fee, which is the difference between the cost of the product and the sales price paid by a customer).

Principals recognize much more revenue than agents for a transaction that looks the same to an end customer, and rightfully so, because they actually own the inventory and bear the risk of loss. Creative and misleading practices arise whenever a company that effectively bears no inventory risk (an agent) accounts for sales as a principal and records revenue at the much higher gross amount.

Let’s look at eBay, the online auction house, to understand the difference between a principal and an agent more clearly. Essentially, eBay’s business is a matchmaking arena in which buyers and sellers find each other, and eBay earns a fee for providing the platform. For example, if you sell your car on eBay for $20,000, eBay will keep a portion of the sale (say $500) as a service fee. As an agent, eBay naturally uses the net method and records the $500 service fee as its revenue. Certainly, eBay should not be entitled to record the gross amount of the sale ($20,000), as it did not really sell the car. As shown in the illustration in Table 4-1, if eBay were to inappropriately recognize revenue under the gross method, its revenue would be massively overstated (although its profit would be the same). Thus, eBay would be fooling investors into thinking that it was a much larger company than its economic reality.

Is Priceline a Travel Agency or an Airline/Hotel Conglomerate?

In contrast to eBay, Internet travel agency Priceline.com Inc. uses the gross method for some of its transactions. For example, on certain transactions in which you “name your price” and purchase a $200 hotel room, Priceline records the entire $200 as revenue. This policy appears to belie the underlying economics of Priceline’s business, which seems to be nothing more than a matchmaking service that bears limited risk of economic loss on the hotel and plane tickets that it sells.

Enron Couldn’t Resist.

Similarly, Enron’s dazzling revenue growth in the late 1990s was aided by its aggressive accounting practice of grossing up sales in its trading business. When typical Wall Street trading firms like Goldman Sachs and Citigroup broker a trade, they understand that they are merely serving as the middleman or agent of the transaction. Accordingly, they record as revenue the related brokerage fee or commission. They would not dare (we hope) to record the gross amount of a trade (i.e., the price of the security plus the fee) as revenue.

Enron, however, accounted for trades considerably more aggressively. Rather than recording just the brokerage fee as revenue, Enron brazenly recognized the entire value of the security or asset traded. Between this ruse and the company’s aggressive use of mark-to-market accounting (discussed in the previous chapter), you now understand two magic tricks that Enron used to rapidly ascend to the “$100 billion club.” If all financial institutions accounted for their trading businesses the “Enron way,” revenue for many banks would be in the trillions.

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Recording Bogus Revenue

• Recording revenue from transactions that lack economic substance

• Recording revenue from transactions that lack a reasonable arm’s-length process

• Lack of risk transfer from seller to buyer

• Transactions involving sales to a related party, affiliated party, or joint venture partner

• Boomerang (two-way) transactions to nontraditional buyers

• Recording revenue on receipts from non-revenue-producing transactions

• Recording cash received from a lender, business partner, or vendor as revenue

• Use of an inappropriate or unusual revenue recognition approach

• Inappropriately using the gross rather than the net method of revenue recognition

• Receivables (especially long-term and unbilled) growing much faster than sales

• Revenue growing much faster than accounts receivable

• Unusual increases or decreases in liability reserve accounts

Looking Ahead

Chapters 3 and 4 addressed techniques for inflating revenue. These tricks included either recognizing revenue too early or recording revenue that, in whole or in part, was bogus. Chapter 5 looks at techniques for inflating income, but it moves further down the Statement of Income. While they are not part of revenue, one-time gains may create distortions in the operating or net income of a company.

5 – Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 3: Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities

When a magician wants to make a rabbit appear out of thin air, he may tap a wand or say the magic word abracadabra. Not to be outdone, corporate executives have their own way of creating something out of nothing when it comes to reporting earnings. Executives don’t need special props, though, and they don’t need to use special words like abracadabra. All they need is a few simple techniques.

One-time gains are akin to the proverbial rabbit in the hat, magically appearing from nowhere. A struggling company may be tempted to use certain techniques that boost income by using onetime or unsustainable activities. Chapter 5 explores such methods, which, if undetected, might confuse investors. This chapter examines the following two techniques used by management to give income a quick, but temporary “shot in the arm.”

Techniques to Boost Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities

1. Boosting Income Using One-Time Events

2. Boosting Income through Misleading Classifications

1. Boosting Income Using One-Time Events

The Dot-Coms Were Coming, and the Blue Chips Were Scared

During the late 1990s, “dot-com” technology start-ups captivated investors’ attention, while older technology stalwarts yearned to regain their luster. Just the simple act of adding “dot-com” to the end of a company name led investors to immediately pay more for the stock. The actual economic performance and fundamental health of these businesses seemed to be of little interest to investors, who became intoxicated with the potential for insane growth in the new economy or the potential for the company to be acquired at a tremendous premium. Some of these companies flourished (Yahoo!), others joined forces with old-line businesses (AOL merged with Time Warner), and many just went bust (eToys went from a market value of $11 billion in 1999 to bankrupt in 2001). Investors were so focused on these up-and-comers that technology blue chips like IBM, Intel, and Microsoft were viewed as old fuddy-duddies.

IBM indeed ran into a rough patch during 1999, as the company’s costs increased faster than revenue. As Table 5-1 shows, cost of goods and services (CGS) grew 9.5 percent in 1999, while revenue was up 7.2 percent, resulting in a lower gross margin. However, somehow IBM’s operating and pretax profits jumped a very impressive 30 percent.

The large discrepancy between revenue and operating income growth should have tipped off diligent investors to do some further digging. Since by reading this book, you are now considered a diligent investor, let’s take a close look at the Statement of Income found in IBM’s 10-K filing (shown in Table 5-1). One thing that should immediately stand out is the 11.6 percent

decline

in selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses, in contrast to the 9.5 percent

increase

in the CGS category. Second, the 30 percent growth in both operating and pretax income seems very surprising on just 7.2 percent sales growth, unless the company also had a large onetime gain that was hidden from view—or had chosen another shenanigan to boost income or hide expenses.

And that is precisely what happened. A footnote in the 1999 10-K disclosed that IBM booked a $4.057 billion gain from selling its Global Network business to AT&T and curiously included that gain as a

reduction in the SG&A expense

. In so doing, IBM magically hid its deteriorating operations from many investors.

As Table 5-2 illustrates, the results, excluding the one-time gain, would have appeared dreadful in comparison to IBM’s reported numbers. Adjusting IBM’s 1999 results by simply removing the gargantuan gain that was improperly bundled into SG&A expense would cause the expense to jump from $14.729 to $18.786 billion. Operating income would, in turn, decline by the same amount, from $11.927 to $7.870 billion. As a result, both operating and pretax income would be sliced by $4.057 billion.

Now we can compare the results (as reported versus our adjusted figures that excluded the gain) and clearly see the dramatic differences. SG&A really

increased

by 12.7 percent (rather than the reported

decline

of 11.6 percent), and operating and pretax profits actually

declined

by 14.1 and 14.8 percent, respectively (rather than the reported

increases

of 30.2 and 30.0 percent).

Turning the Sale of a Business into a Recurring Revenue Stream

Some companies will sell a manufacturing plant or a business unit to another company, and, at the same time, enter into an agreement to buy back product from that sold business unit. These transactions are common in the technology industry and are often used by companies as a way to quickly “outsource” an in-house process. For example, a cellular phone manufacturer that decides that it no longer wants to make its own batteries may sell its battery manufacturing division to another company. At the same time, since the phone manufacturer still needs batteries for its phones, the two companies may enter into another agreement in which the phone manufacturer purchases batteries from the division that it just sold.

Not surprisingly, such transactions that commingle a one-time event (the sale of a business) and normal recurring operating activities (the sale of product to customers) create opportunities for management to use financial shenanigans. For example, the phone company may take less money for the sale of its battery business if the buyer also agrees to give the company a good deal on future battery purchases. In another type of commingled transaction, a company may sell a business at a deflated price if the buyer also agrees to purchase other goods from the seller at an inflated price.