Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (35 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

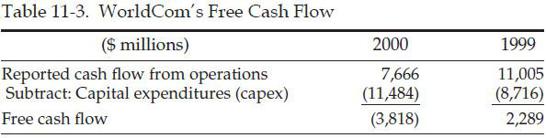

As shown in Table 11-3, calculating free cash flow at WorldCom reveals the extent of the company’s problems: a $6.1 billion deterioration from 1999 to 2000.

Accounting Capsule: Free Cash Flow

Free cash flow measures the cash generated by a company, including the impact of cash paid to maintain or expand its asset base (i.e., purchases of capital equipment). Free cash flow typically would be calculated as follows:

Cash flow from operations

minus

capital expenditures

3. Recording the Purchase of Inventory as an Investing Outflow

“Cost of goods sold” (COGS) is a very apt name for the direct expenses that companies incur to acquire or produce inventory sold to customers. On the Statement of Income, COGS is subtracted from revenue to yield a company’s gross profit, an important measure of the profitability of the company’s products.

The Statement of Cash Flows is sometimes not as straightforward. The economics of purchasing goods to be sold to customers suggests that these purchases should be classified as an Operating activity on the Statement of Cash Flows. Normally, this would be the case. Curiously, some companies treat these purchases as an Investing outflow.

Purchase of DVDs: Operating or Investing?

Consider the case of Netflix Inc., the online movie rental company. As you might imagine, one of the company’s largest expenditures is purchasing the DVDs that it rents out to customers. DVDs are essentially Netflix’s inventory, and therefore the company records its DVD library as an asset on its Balance Sheet. This asset is then amortized (over a period of one year for new releases and three years for back catalog), and, as you would expect, the amortization cost is presented on the Statement of Income as a cost of goods sold. In 2007, Netflix’s amortization of its DVD library amounted to $203 million on revenue of $1.2 billion.

While Netflix’s Statement of Income appropriately reflects the economics of its DVD costs, its Statement of Cash Flows does not. You would think that the purchase of DVDs should be presented on the SCF as an Operating outflow just like the purchase of any inventory (particularly the purchase of the new releases that are amortized for only one year). However, Netflix does not see it that way. Instead, it considers the purchase of DVDs to be the purchase of a capital asset, and therefore the cash outflows are presented in the Investing section. This treatment effectively moves a big cash outflow (payment for DVDs) from the Operating to the Investing section, thereby inflating CFFO.

Interestingly, Netflix’s competitor Blockbuster Inc., a company that is not known for accounting conservatism, changed its accounting for DVD acquisitions at the end of 2005. Previously, Blockbuster had presented DVD purchases as an Investing outflow, just like Netflix. However, after consultation with the regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission, Blockbuster began classifying DVD purchases as an Operating outflow and restated its historical numbers.

Consider Differences in Accounting Policies When Comparing Competitors.

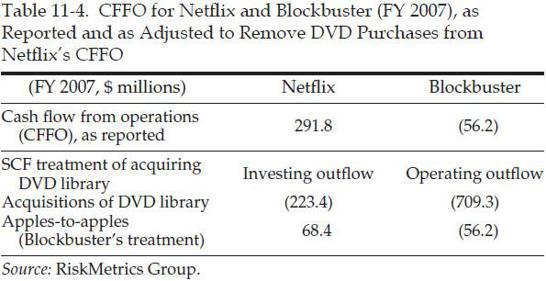

Since Netflix puts DVD purchases in the Investing section and Blockbuster puts them in the Operating section, investors have little ability to compare the CFFO of the two companies without making an adjustment. As shown in Table 11-4, Netflix’s cash flow from operations was much stronger than that of Blockbuster in 2007; however, the difference is much less pronounced after adjusting for the DVD purchases.

Question Any Investing Outflow That Sounds Like a Normal Cost of Operations

. While many analysts claim that reading the Statement of Cash Flows is an integral part of their analysis, many of them fail to read carefully below the Operating section. Simply scanning Netflix’s Investing section would have revealed that the company classified “Acquisitions of DVD library” as an Investing activity. Even investors with only a basic knowledge of Netflix’s business would know enough to realize that acquisition of DVDs represents a normal cost of operations for Netflix.

Tip:

Keep an eye out for this cash flow trick at companies that purchase goods and then lease or rent those goods to customers.

Purchasing Patents and Newly Developed Technologies

Some professional sports franchises fill their team rosters with players whom they scouted, drafted, and developed within their own organizations. Others rely on the “free agent” market to sign proven players (albeit normally at a much higher price). In the same way, some companies rely on their own internal research and development projects to grow their businesses organically, while others choose to grow inorganically by acquiring development-stage technologies, patents, and licenses. While these different business strategies are both means to the same end, the expenditures are often treated differently on the Statement of Cash Flows. Specifically, cash paid to employees and vendors for internal research and development would be reported as an Operating outflow. However, some companies report cash paid to acquire already researched and developed products as an Investing outflow.

In certain industries, acquiring development-stage technologies is considered commonplace. For example, small biotechnology research companies often develop new drugs and then sell the rights to those drugs to a larger pharmaceutical company once FDA approval is near. The pharmaceutical company then, as owner of the drug, reaps all of the profits. When analyzing the pharmaceutical company’s business, you certainly should be considering the cash paid to acquire the drug rights. However, since the payment will be classified in the Investing section, many investors will have no idea that it even exists.

Tip:

Keep an eye out for this treatment at companies where individual patents or rights agreements have a significant impact on the business, such as pharmaceutical and technology companies.

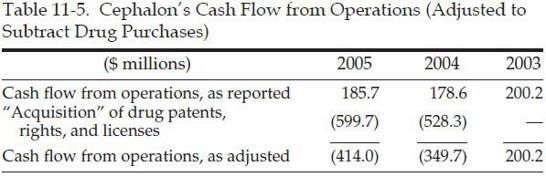

Consider the case of biopharmaceutical company Cephalon. Looking to continue its rapid pace of growth, Cephalon went on a $1 billion shopping spree in 2004 and 2005, snapping up patents, rights, and licenses related to several newly developed drugs. Cephalon presented these cash payments as “acquisitions” and dumped them into the Investing section of the Statement of Cash Flows. Had they been classified as Operating, CFFO instead would have been severely negative in both years. (See Table 11-5.)

I’ll Gladly Pay You Tuesday for a Hamburger Today

In an interesting twist, Biovail Corporation, Canada’s largest pharmaceutical company, gained ownership of certain drugs by purchasing the rights through noncash transactions. Instead of paying cash at the time of the sale, Biovail compensated the sellers by issuing a note—essentially, a long-term IOU under which the company would pay cash in the future. Since no cash changed hands at the time of the sale, there was no impact on the Statement of Cash Flows. And as Biovail paid down the notes over time, the cash payments were presented on the SCF as the repayment of debt—a Financing outflow.

Biovail’s noncash purchases of product rights can be thought of in the same light as Cephalon’s patent purchases and Netflix’s DVD purchases. The economics suggest that these purchases relate to normal business operations, yet they are reflected in a very different way on the Statement of Cash Flows. When analyzing Biovail’s ability to generate cash, these purchases should certainly not be ignored.

Look for “Supplemental Cash Flow Information.”

Companies frequently provide information about noncash activities in disclosures in the financial reports called “Supplemental Cash Flow Information.” This disclosure is sometimes found immediately after the Statement of Cash Flows; however, occasionally companies will bury this disclosure deep in the footnotes. For example, Biovail provided the disclosure about its noncash purchases in a supplemental cash flow footnote that came 30 pages after the Statement of Cash Flows:

BIOVAIL’S SUPPLEMENTAL CASH FLOW DISCLOSURE

In 2003,

non-cash investing and financing activities

included the long-term obligation of $17,497,000 related to the acquisition of Ativan® and Isordil®, and the subscription to $8,929,000 Series D Preferred Units of Reliant in repayment of a portion of the loan receivable from Reliant. In 2002, non-cash investing and financing activities included long-term obligations of $99,620,000 and $69,961,000 related to the acquisitions of Vasotec® and Vaseretic®, and Wellbutrin® and Zyban®, respectively, as well as a long-term obligation of $80,656,000 related to the amendments to the Zovirax distribution agreement. [Italics added for emphasis.]

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

• Inflating operating cash flow with boomerang transactions

• Improperly capitalizing normal operating costs

• New or unusual asset accounts

• Jump in soft assets relative to sales

• Unexpected increase in capital expenditures

• Recording purchase of inventory as an investing outflow

• Investing outflows that sound like a normal cost of business

• Purchasing patents, contracts, and development-stage technologies

Looking Ahead

As Chapter 11 showed, shifting operating cash outflows to the Investing section can be quite enticing for managements that hope to impress investors with stronger cash flow. Well, it seems that management cannot get enough of a good thing. Chapter 12 shows how, just by a quirk in acquisition accounting, management can shift a boatload of working capital that normally depresses operating cash flows to the Investing section.

12 – Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 3: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

The Friday after Thanksgiving is generally considered the unofficial start of the holiday shopping season. Traditionally, it is one of the biggest shopping days of the year, if not

the

biggest. The day has long been called “Black Friday,” since many people are hopeful that it will be the day when retailers move “into the black” (slang for “turning a profit”) for the year. Every time Black Friday approaches, retailers are quick to remind us of all the holiday shopping that we need to do. They offer huge sales and fill the airwaves and newsprint with “Shop ‘Til You Drop” advertisements trying to lure us into their stores.