A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (28 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Other patterns of whole-steps and half-steps can be used to make other types of scales. Some of these are closely related to the major scale, while others are more distantly related. In the remainder of this chapter, we'll explore various ways to construct scales, and show how they can be used in conjunction with chords.

THE GREEK MODES

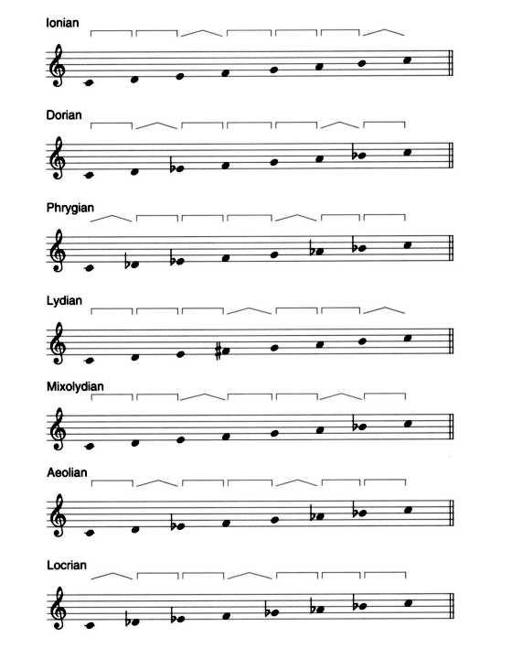

Starting with the major scale, we can generate six new scales simply by choosing a different note for the tonic. The usual term for the scales created in this way is modes. Several of the modes are often used in improvisation, so it's important to understand them. They're shown in Figure 7-10, and again in Figure 7-11. Table 7-1 provides the same information as Figures 7-10 and 7-11; some musicians may find the concept easier to grasp when it's presented in tabular form.

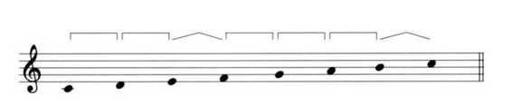

Figure 7-9. One octave of a C major scale. The whole-steps are marked with square brackets, the half-steps with angled brackets. This pattern of whole-steps and half-steps is repeated in all of the major scales.

Figure 7-10. By using the same set of whole-steps and half-steps that are found in the major scale, but starting and ending on a different tonic note, we can generate seven different melodic modes. The Ionian mode (which is the same as the major scale) starts and ends on C, the Dorian mode on D, the Phrygian mode on E, the Lydian mode on F the Mixolydian mode on G, the Aeolian mode on A, and the Locrian mode on B.

Figure 7-11. Here, the seven modes shown in Figure 7-10 have been transposed so that they all start and end on C (the tonic). The pattern of whole-steps and half-steps is marked as before, with square brackets for whole-steps and angled brackets for half-steps.

The term "mode" means something like "manner" or "method" It's a way of saying that we're doing the same thing we were doing before, only in a different way. In this case, we're using the arrangement of whole-steps and half-steps found in the major scale - two whole-steps and then a half-step, followed by three whole-steps and a half-step - but we're calling a different note the tonic. Or, to look at it a different way, we're sliding the half-steps to the left or right so that they fall in a different spot in relation to the tonic. The major scale, which is also called the Ionian mode, starts with two whole-steps. If we consider D the tonic rather than C, the mode starts with one whole-step followed by a half-step, then three more whole-steps and so on. This is called the Dorian mode. The next mode, Phrygian, runs from E up to E on the white keys of the keyboard, so it begins with a half-step. Note that this mode is quite different from the E major scale, because the latter uses four black keys (F#, G#, C#, and D#), while the E Phrygian mode uses only white keys.

Our ears are so used to hearing the major scale that if you simply start playing the white keys on the keyboard, before long your ear will probably tell you you're playing in C major, no matter what note you try to hear as the tonic. It may be difficult to hear the Dorian mode or any of the other modes as a distinct entity. Hearing them will get easier when we start playing them in combination with chords.

Most of the names of the modes originated during the Medieval period; others were added later. While Medieval music theorists were fond of using terminology drawn from ancient sources, the modes have very little relationship to the music played in ancient Greece. The Greeks gave similar names to some of their scales, but we have very little idea what those scales actually sounded like. The modes used in Medieval church music were somewhat different from the modern modes with the same names, and are of interest only to musicologists, so unless you're working toward a music degree there's no reason for you to clutter your brain with them.

USING MODES WITH CHORDS

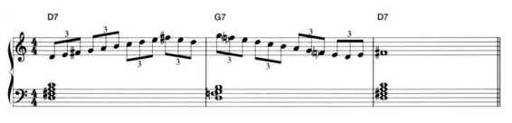

An important reason why modes are important is because they give us a repertoire of scales that can be used easily in conjunction with specific types of 7th chord. To see how this works, play the music in Figure 7-12. To begin with, the scale in measure 1 obviously works with the D7 chord: It contains all of the notes in the chord. Now figure out where the whole-steps and half-steps are in the scale used in measure 1. Since this scale has one sharp, you can probably see at a glance that it must be a G major scale (Ionian mode with a tonic note of G). But in the heat of improvisation, trying to remember that you need to play a G major scale over a D7 chord is likely to be a bit confusing. If you look at this scale as a mode whose tonic note is D (the same note as the root of the underlying chord), you'll discover that you're looking at D Mixolydian.

Figure 7-12. Since blues progressions often use a dominant 7th chord as the 1, this D7-G7 progression is most likely a 17-IV7 progression in the key of D. Over each of the 7th chords, a soloist can play in Mixolydian mode. The scale shown above the D7 is D Mixolydian, and the scale above the G7 is G Mixolydian.

As Figure 7-11 shows, Mixolydian mode has the same structure as a major scale, except that the 7th step (the leading tone) is lowered. This lowered step corresponds to the minor 7th in a dominant 7th chord (Cb above the D root). So Figure 7-12 illustrates the first concept in applying modes:

Over an unaltered dominant 7th or dominant 9th chord, use the Mixolydian mode whose tonic is the same as the root of the chord.

The same thing happens in measure 2 of Figure 7-12. The chord, G7, is an unaltered dominant, so the scale to play over it is G Mixolydian. This figure illustrates another important concept as well: In many types of pop music, but especially jazz and blues, the scale or mode from which melody notes are drawn is quite likely to change when the chord changes. Experienced improvisers learn a variety of modes and scales in all 12 keys, so as to be able to switch from one to another fluidly.

When analyzing which mode is used in a melodic line, it's important to understand that the note on which the line starts (or ends) doesn't matter. To make it easier for you to see that the modes used in Figure 7-12 are Mixolydian, I arranged the music in such a way that the right-hand line in each measure started on the tonic note of the mode. But this is not necessary. A line can start or end on any note of the mode. Also, Figure 7-12 is written so that the right-hand line in each measure moves in a scalewise fashion, one step at a time. In real-world soloing, it would be the exception rather than the rule that a line would do this for an entire measure. In most types of classical music, running up or down a scale is stylistically appropriate, but in jazz and pop, straight scales tend to sound quite square and stiff. Many of the lines shown in this chapter are intentionally kept very simple, so that they'll be easier for you to analyze.

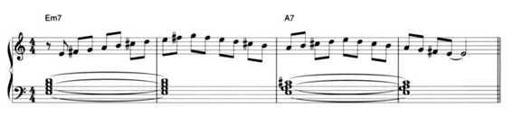

Now look at Figure 7-13. The chord in the first two measures is a minor 7th. If we assume that the mode of the notes in the right hand has the same tonic (E) as the root of the Em7 chord, by analyzing the pattern of whole-steps and halfsteps you'll be able to see that this line is in E Dorian mode. Whenever you see an unaltered minor 7th chord, you can play in the Dorian mode whose tonic is the same as the root of the chord.

Measures 3 and 4 of the same passage call for a dominant 7th chord whose root is A. (Most likely, we're looking at a Ilm7-V7 progression in the key of D.) The mode used above the A7 is A Mixolydian, as explained above. If you examine the right-hand line in this figure, however, you'll see that the scale, which contains two sharps, doesn't change when the chord changes. This fact points out another important concept:

Figure 7-13. Above a minor 7th chord, you can use the Dorian mode. In this example, E Dorian is used above the Em7. Above the A7, A Mixolydian is used, as in Figure 7-12. Note that E Dorian and A Mixolydian share all of the same notes.

Over a IIm7-V7 progression, use the Dorian mode over the IIm7 and the Mixolydian over the V7. Because of the relationship between the chord roots, the two modes will contain exactly the same notes.

The Ionian mode (the major scale) is used whenever the chord is an unaltered major 7th type. Measure 2 in Figure 7-14 shows this. Here again, the E6 Ionian mode has the same underlying scale steps as the F Dorian and B6 Mixolydian. In real-world progressions, however, you can't necessarily assume that you'll be playing in the same scale (and calling it by a different name) when the chord changes. Figure 7-15 shows what happens to the progression in Figure 7-14 when we use a tritone substitution in place of the V7 chord. The notes in measure 2 are drawn from the E Mixolydian mode, which is utterly different from the B6 Mixolydian used in Figure 7-14. In fact, these two modes have only two notes in common: D and G#/A6. These two notes are the major 3rd and minor 7th of the two dominanttype chords.