A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (38 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

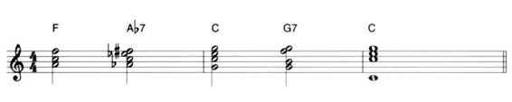

The German 6th is the enharmonic equivalent of a dominant 7th chord built on the flatted 6th step of the scale - 6VI7 We've already seen this type of chord a couple of times in this book. In Figure 8-12, for instance, it provides a pivot in a modulation. However, the German 6th is not called a 6th chord because it's built on the 6th step of the scale. (Nor is there anything German about it.) It gets its name from the enharmonic spelling of the 7th of the chord as an augmented 6th. Figure 8-31 shows this spelling (an A67 chord in C major in which the 7th of the chord is spelled as F# rather than G6), and also shows a characteristic use of the chord.

Figure 8-31. The German 6th chord (the second chord in measure 1) gets its name from the augmented 6th interval between its root and the upper note. In classical music, it most often precedes either a I chord in second inversion, as shown here, or a V chord.

Note the smooth chromatic voice leading with which the A in the F chord proceeds downward to the G in the bass of the second-inversion C chord, while the F moves upward to the top G. When using this progression, a classical composer would probably have spelled the E6 enharmonically as a D#, because that voice resolves upward to the E. Spelled with a D#, the chord is sometimes referred to as an English 6th. (Again, there's nothing especially English about it.) If the D#/E6 is replaced with a Da, the chord is called a French 6th. The French 6th in C is enharmonically the same as a D765 or A6765 chord.

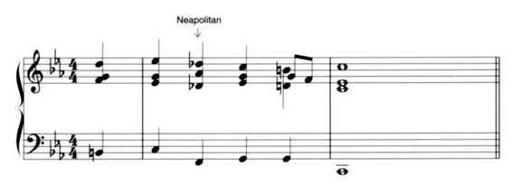

The Neapolitan 6th is a major triad built on the flatted 2nd step of the scale - for example, a D6 triad in the key of C. It gets its name from the fact that it was originally heard most often in first inversion, which meant there would be an interval of a 6th between the bass note and the root of the chord. During the cornmon practice period, the Neapolitan was used most often when the music was in a minor key, as in the progression in Figure 8-32.

Note that the secondary dominant of the Neapolitan (V7 of 611) is enharmonically the same as the German 6th. Composers like Mozart and Haydn routinely used this fact to modulate temporarily to the key of the 611, in the manner shown in Figure 8-33. After arriving at the 611 chord, they might stay in this key for several bars before returning to the original key.

Figure 8-32. The Neapolitan 6th chord (which is not a 6th chord) is a major chord built on the flatted 2nd step of the scale. As this passage shows, in classical music it was most often used in a minor key, and functioned more or less as a substitution for the 11 chord, which in the natural minor scale would be a diminished triad.

Figure 8-33. The German 6th (a 6V17 chord) can be used as a secondary dominant leading to the Neapolitan chord (A67 to D6 in the key of Q.

HOW TO COMP FROM A CHORD CHART

Theoretical knowledge is a wonderful thing, no doubt, but the point of learning about chords is to be able to use them in actual musical situations. Unless you're strictly a classical musician or composing your own material, that probably means playing from chord charts.

There's a lot more to playing from a chart than understanding what notes are used in the chords on the chart. First and foremost, you need a thorough working knowledge of your instrument. But even if you're a virtuoso, your ability to comp (accompany) will depend on your familiarity with the musical style you're being called on to play. Country, pop, Latin, jazz, and blues all have their own characteristic rhythms and chord voicings, and a player who is proficient in one style may be a complete duffer in another.

Sadly, I don't have the kind of encyclopedic knowledge of styles that would allow me to give you the Seven Basic Country Strums, 20 Ultimate jazz licks, or whatever. I can, however, suggest some guidelines that will help you sharpen your skills.

Learn the style you want to play. Buy CDs and listen to them analytically. Focus on what your instrument is doing in each song. Listen to the rhythms and the chord voicings. Notice how the parts played by your instrument fit with those played by other instruments. Analyze the chord progressions. Go to concerts and listen to the same things.

Practice with a metronome. Comping is all about getting from one end of the tune to the other with no serious mistakes. Staying with the rhythm is essential. In the heat of a concert, it's often preferable to play a wrong note rather than fumble around and lose the groove. If you're having trouble with a particular chord, slow the metronome down and practice the entire song until you can move through the troublesome chord without hesitation.

Listen to the other players. Listen to their rhythms and chord voicings. If two instruments are chording in the same range, the sound will tend to be cluttered, so you may need to move your voicings up or down to a pitch range that isn't so busy. You may also discover that you're playing a minor 9th (which is called for in the chart) while someone else is steadfastly playing a natural 9th. Depending on the situation, you might choose to change what you're playing or to point out the problem to the other player in a tactful way.

Rhythm playing seems to work best when the various instruments accent some of the same beats, but not all of them. If there are anticipations in a chord chart (places where the new chord starts half a beat ahead of the bar line) it's especially important for the whole band to be together. Throwing an accent into a hole - a spot where the other players are resting - can add a lot of interest to your part. As long as it's the right accent, of course.

Memorize the charts. Chord progressions have their own logic and flow, which generally makes them pretty easy to memorize. Many charts, however, contain one or two tricky spots where your ear may lead you astray. If necessary, use verbal reinforcement: At the beginning of the tune, remind yourself, "First time A minor, second time A7," or whatever.

Analyze the charts. Chords don't exist in a vacuum. In a well-written piece of music, each chord leads to the next one in a logical way. You might discover, for instance, that all of the chords in the bridge are drawn from a D major scale. The fact that they have lots of common tones might suggest certain types of voicings that wouldn't occur to you if you were just looking at a series of roots.

THE OUT CHORUS

In this book I've tried to set out the basic tools musicians need for understanding chords and harmony. Given the vastness of the subject matter, to say nothing of my own slightly less than encyclopedic knowledge and my publisher's very rea sonable assessment that you probably wouldn't want to buy a 700-page book, the treatment has inevitably been sketchy at times. To become a master of the harmonic universe, you'll need to explore further on your own. The tools you'll need - scores, recordings, performances by your favorite musicians, and your own in- strument(s) of choice - are readily accessible. The harmonic vocabulary available to musicians in the 21st century is not only vast but capable of amazing subtleties of expression. Knowing the vocabulary is essential for any serious musician, but what you choose to say with it is entirely up to you.

Happy harmonizing!

QUIZ:

1. What is it called when the harmonic rhythm doubles in the last two bars of a blues progression?

2. How many four-bar phrases are there in each chorus of a typical blues song?

3. Define the term "chorus" as it's used in jazz.

4. What is a tag?

5. What term is used to describe a progression in which the music changes to a new key?

6. What is an unchanging bass note called?

7. What term is used to describe the chord voicing technique in which one voice moves upward while another moves downward?

8. What is the root of a Neapolitan 6th chord in the key of D major? What note would usually appear in the bass?

APPENDIX A:

HOW TO READ SHEET MUSIC

irst and foremost, music is about making sounds. The question of how to write down a set of instructions that will enable others (or enable you yourself at a later date) to recreate the sounds is only of secondary importance. On the other hand, no matter how fantastic you are at playing your instrument, if you don't know how to read music notation you're going to be at a serious disadvantage when it comes to communicating your ideas to other musicians, and at understanding their communications in return.

irst and foremost, music is about making sounds. The question of how to write down a set of instructions that will enable others (or enable you yourself at a later date) to recreate the sounds is only of secondary importance. On the other hand, no matter how fantastic you are at playing your instrument, if you don't know how to read music notation you're going to be at a serious disadvantage when it comes to communicating your ideas to other musicians, and at understanding their communications in return.

The purpose of this Appendix is not to provide an exhaustive treatment of the minutiae of music notation. The goal is much simpler: to enable you to understand and interpret the printed examples in this book. Many details (such as ties, triplets, and articulation marks) are omitted entirely. If you're interested in learning more, the standard reference work to dive into is Music Notation, by Gardner Read [Taplinger].

I'm going to assume you have access to a keyboard instrument of some kind. A piano is ideal, but electronic keyboards have at least one advantage: They never go out of tune. Learning to read music starting with an instrument other than a piano is eminently feasible, but few other instruments let you play chords with as much freedom, or provide as much visual feedback on the shape of the chord while you're doing it. Since being able to find, play, and understand chords is the point of this book, we're going to use the keyboard as the basis for explaining notation. Whether you ever acquire any keyboard dexterity or simply pick out the examples one note at a time is entirely up to you.