A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (25 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Figure 6-29. The major 6th chord (in this case, C6) contains the same notes as a minor 7th chord (Am7) in first inversion.

If the chord contains no notes except a major triad and an added 6th, the chord symbol is simple: The chord in Figure 6-29 is called a C6. But the 6th is the same note of the scale as the 13th. So why not call this chord a C 13? Because the existence of a 13th would imply the existence of a 7th (definitely), 9th (probably), and 11th (possibly). In the absence of these upper notes, it makes much more sense, both to make it easier to interpret the chord symbol and in terms of how we hear the chord, to consider the note a 6th.

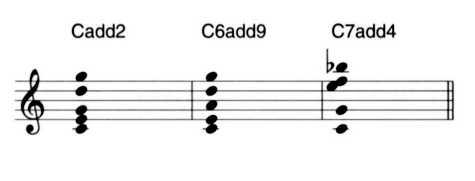

When you want to add a tone to a chord, but you don't want to call it a 9th, 11th, or 13th because you don't want to imply the presence of other tones, the way to do it is with the handy term "add" The first chord in Figure 6-30, for instance, is a simple C major triad to which a 2nd (D) has been added: It's an add2 chord. If the chord had a 7th, we could call it a C9, because the D would be the 9th of such a chord. But since there's no 7th, the correct abbreviation is Cadd2. We could just as easily call it a Cadd9, because "add" means "this isn't a real 9th, it's just a note that has been grafted on:" If the note one step above the root is added, it's a matter of taste whether to call the chord an add2 or an add9. I've seen pop songwriters use the symbol C2 for this chord. There's nothing wrong with this symbol except that it doesn't quite fit into any system.

The "add" nomenclature can be used to add a 4th to a chord. If the chord were called an 11 rather than an add4 (or addl 1), it would imply the presence of a 7th and 9th.

In the absence of any other information in the chord symbol, the 6th is always major. A chord containing only a triad and a minor 6th will normally be called an add66 or add613.

FOURTH-CHORDS

Since stacking 3rds leads to so many harmonic possibilities, it's natural to wonder what might happen when we stack other intervals. Stacking 2nds (as in Figure 6-31) yields a variety of structures known as cluster-chords. Cluster-chords can be used to create dissonances, but there's no easy way to string them together in meaningful chord progressions.

Stacking 4ths is a bit more interesting. A stack of three or more 4ths is called a fourth-chord. Fourth-chords are somewhat ambiguous tonally: When a progres sion is written using fourth-chords, it's not usually possible to say what key it's in. This effect can be seen in Figure 6-32. While the progression has a clear sense of harmonic movement, it lacks a tonal center. In fact, it's not even possible to say what the root of a fourth-chord is with any certainty, because it contains neither of the notes found in a triad (the 3rd and 5th) that help us identify the root of the triad. Accordingly, there are no accepted names or chord symbols for fourthchords. Some theorists feel that the second note in a fourth-chord, counting up from the bottom, feels like the root.

Figure 6-30. When an extra note needs to be added to a voicing, the notation "add" is used in the chord symbol. The 6 chord is technically an "add" chord, but if the major 6th is the only added note, there's no need to clutter up the chord symbol: Calling it a 6 chord does the trick. The third chord here can't be called a C7sus4, because a sus4 chord contains no 3rd (the E), and it can't be called a C11 because there's no 9th (D). The "add4" notation correctly indicates the clash between the 3rd and 4th.

Figure 6-31. A cluster-chord built out of stacked 2nds can be useful for injecting some dissonance into a texture. Depending on the surrounding harmonic context, the voicing shown might (or might not) be heard as a Cmaj9 chord - in other words, as a chord constructed using stacked 3rds, voiced in an unusually closed position.

It's also possible to stack 5ths or 7ths. From the fact that a 5th is an inverted 4th and a 7th is an inverted 2nd, you might expect that stacked 5ths would have the same harmonic effect as stacked 4ths, and stacked 7ths the same effect as stacked 2nds. But there's a difference, as Figures 6-32 and 6-33 show. In chords built using stacked 5ths or 7ths, the lowest note is easily perceptible as the root. A chord built by stacking 6ths can always be analyzed as a conventional chord containing stacked 3rds, but with an open voicing.

Figure 6-32. When a chord is formed by stacking 5ths, the bottom note will usually be perceived as the root, even though the chord has no 3rd.

Figure 6-33. As with stacked 5ths, chords formed by stacking 7ths will be usually be interpreted as having the root on the bottom.

The 4ths in a fourth-chord are usually perfect 4ths. If any of them is augmented or diminished, the chord becomes easier to hear and analyze as an extended stacked-3rds chord with one or more altered or suspended notes. You can create useful voicings this way, but whether to call them fourth-chords becomes a matter of personal preference. Starting with the first chord in Figure 6-34, for instance, we can try raising and lowering each tone in turn to see what sort of harmony results. Doing this to the lower two notes gives us the voicings in Figure 6-35. As you can see, these chords are not hard to analyze as combinations of stacked 3rds.

Figure 6-34. A chromatic progression using fourth-chords. Fourth-chords lack a clearly perceptible root, so they aren't usually indicated with chord symbol abbreviations.

Figure 6-35. Altering a single note within a fourth-chord will usually turn it into some sort of stacked-3rds voicing. Here, the lower note (left) and second note (right) are altered.

Figure 6-36. More 4ths can be stacked, producing a more intense sound. In some big-band jazz charts, this type of voicing is used in a sustained chord at the very end of the piece, with a shrieking trumpet playing the very top note. More and more instruments can be added one by one to the top of the chord (E6, A6, and so on), producing a dense and towering sonority.

Stacking more 4ths gives us a chord structure that's more intense, and also more harmonically ambiguous, as Figure 6-36 shows. The clash between the low A and the high B6 in this chord is especially jarring.

Fourth-chords are most often played in close position, as in Figure 6-36, rather than being revoiced with various notes in other octaves. Sometimes one of the notes is moved up or down by an octave, but when we start moving individual notes up and down, any fourth-chord with six or fewer notes becomes analyzable as a conventional stacked-3rds chord. The fourth-chord in Figure 6-35, for instance, which is shown with no chord symbol, is actually analyzable as an F7sus4. This will become clear if you move the C up an octave. Likewise, the sixnote stack in Figure 6-36 can be analyzed as a B6maj9add6. To hear this a bit better, switch the octaves of the B6 and the A. For that matter, the stacked 2nds in Figure 6-30 are readily analyzable as a Cmaj9.