A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (24 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

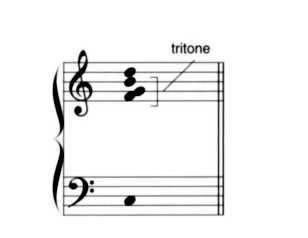

Figure 6-20. When playing a tritone substitution, it may not be necessary to change the upper notes of the chord voicing in any way. Shown here are three different ways of voicing either a G7-type chord or a D67-type chord.

Figure 6-2 1. Another ambiguous voicing. Lacking any other information, this would appear to be a B6maj7 chord in third inversion - but see Figure 6-22.

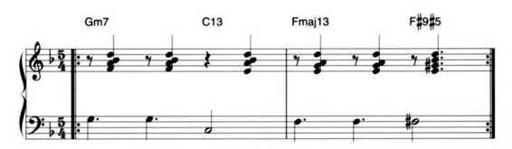

Figure 6-22. In this riff, the notes in Figure 6-21 are used to voice Gm7 and C13 chords. This riff illustrates a technique that is often used with extended voicings: Two or more notes may continue without changing through several different chords. As each new root is played, the notes acquire different harmonic identities.

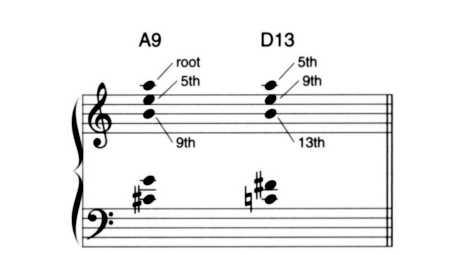

Figure 6-23. Another example in which three notes are sustained from one chord to another. If you have trouble hearing the second chord as a D, play the D root in a lower octave along with the voicing shown.

Note groups consisting of stacked 4ths are found in a number of 9th, 11th, and 13th chords. In Figure 6-23, for instance, the stacked 4th shape in the right hand remains fixed, while the two lower voices each drop by a half-step.

OTHER CHORD TONES

Take a look at Figure 6-24. The chord on the second beat is clearly a C9 - but what are we to call the chord on the first beat? Possibly the F is an 11th. But remember what was said earlier about how the use of higher notes within a stack of 3rds implies the presence of lower notes. Remember also that the 3rd of a chord is one of the most important notes for establishing the identity of the chord. In some situations the 3rd is even more important than the root. So the chord on the first beat of this example is a puzzle: It has no 3rd.

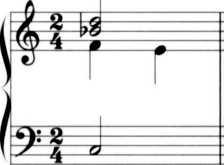

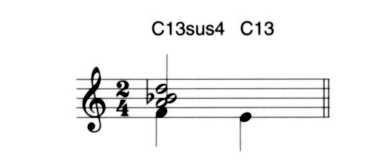

Figure 6-24. A suspended 4th (the F) resolving downward to the 3rd of a C9 chord.

In this type of voicing, the F is called a suspended 4th. In chord symbols, this is abbreviated "sus4," and the popular term for chords that use suspended 4ths is "sus chords" Another way to look at this note would be as an augmented 3rd, but that terminology is never used, because there is no basic triad that contains an augmented 3rd. The note is considered "suspended" because it feels as if the voice playing the note is about to drop from the 4th down to the 3rd. This movement, in which the suspended 4th resolves downward, is shown in Figure 6-24.

The general rule is that a sus4 chord never contains a 3rd: It contains a 4th instead. It can contain any of the other tones in the 13th chord stack, but normally a sus4 will be a dominant-type chord. It would be rare to hear a suspended 4th in combination with a major 7th. To see why, look at Figure 6-25. The suspended 4th and major 7th form a tritone. As a result, we tend to hear the chord in this example not as a Cmaj9sus4 but as a G7/C. It's a useful chord, but it's not really a C chord.

Figure 6-25. This might appear on paper to be a Cmaj9sus4 chord (the F 4th replacing the E 3rd), but perceptually, and therefore functionally, it's a G7 above a C root. The tritone interval between the F and a guides the ear to perceive the G dominant shape.

A suspended 4th is usually in the middle of a chord voicing, or on top. When it's used in the bass, the identity of the chord root will be obscured. If the suspension resolves to the 3rd, however, it can be used in the bass, as in Figure 6-26.

Figure 6-26. Normally a sus4 should not be used as the lowest note in a voicing, unless it resolves to the 3rd. On its own (assuming no bassist is playing the C), the C13sus4 chord here will be heard as a 86maj7, not as a C chord. The movement from F down to E, however, makes it clear that we've been hearing a C13.

If the sus4 is the top note in a C7sus4 voicing, some arrangers will call the chord a C11. I don't recommend this usage, because I feel the "11" in the symbol implies the presence of a 3rd. Another correct name for the chord would be B6/C.

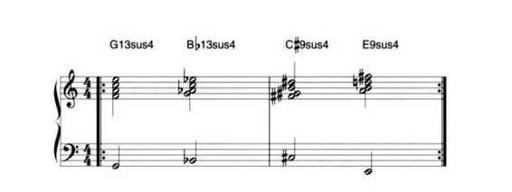

The term "suspended" seems to imply that the 4th will eventually resolve downward to the 3rd. In 19th-century classical music, such a resolution would have been all but inevitable, as the quote from Harmony at the beginning of this chapter suggests. But in more modern styles, no resolution of the suspended 4th is necessary. Progressions in which a sus4 chord leads directly to another chord are very practical. The next chord could even be another sus4 chord, as in Figure 6-27

Figure 6-28 takes the idea of suspended 4ths and extends it a bit. I wrote this pattern in order to explore the possibility that the chords in Figure 6-11 might be more useful than they appear. I'm not entirely sure how to analyze the last chord in this figure, because it's right at the edge where functional harmony turns into bitonalism. But it's an interesting chord. Since there are an infinite number of ways to combine chords, this book couldn't possibly cover all of them, but perhaps this figure will inspire you to dream up some outlandish progressions of your own.

Figure 6-27. This jazzy chord riff has no clear I chord - in other words, we can't quite say what key it's in - because the roots move through a series of minor 3rds. It illustrates an interesting way to use unresolved sus4 chords.

Figure 6-28. This Latin riff uses the unconventional inversions in Figure 6-11. Although the D9 is a dominant chord, in this riff it functions as the tonic, not as a dominant. The second chord can be analyzed as C7/D or as a D9sus4 with a 86 slapped into the middle of it. Call it a D9613sus4 if you like. In the C7/A, this entire voicing is suspended over the A root. The A root implies a dominant in the key of D, but most of the expected dominant notes are missing. If you analyze this chord as an A7#969 with no 3rd, I won't argue with you, but calling it a C7/A is easier and arguably says more about the actual sound of the chord. Note that this same riff will sound much more normal (and perhaps less interesting) if you replace the 86's with A's.

Next, consider the much more conventional chord in Figure 6-29. There are two ways to analyze this chord, both of them correct: We can call it an Am7 in first inversion (the notes A-C-E-G with the C in the bass), or we can look at it as a C major triad with an extra note a 6th above the root - an added 6th. When the C is the lowest note, the major triad has such a strong sound that the latter interpretation makes more sense. The major 6th chord was used a lot in jazz and pop in the 1930s, but today it sounds old-fashioned, and tends to be avoided except when the arranger wants to throw in something sweet or corny.