A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (30 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

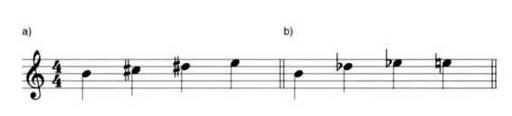

Figure 7-22. The ascending melodic minor scale in C. This scale has a different pattern of whole-steps and half-steps. It also contains an interval of an augmented 5th (between the 3rd and 7th steps, which here are E6 and B). This interval is not found in any of the major scale modes.

This fact might suggest to you that we can generate a whole new set of modes by performing the same type of transformation on the ascending melodic minor scale that we performed on the major scale. In fact, this is an eminently feasible procedure. While the modes created in this way, which are shown in Figure 7-23, don't have names, some of them are quite useful in conjunction with certain of the altered chords introduced in Chapter Six.

Figure 7-23. The ascending melodic minor can be played in seven different modes. The fourth mode shown here, containing a raised 4th and a lowered 7th, was used by 20thcentury composer Bela Bartdk, and is sometimes referred to as "the Bartdk scale." The enharmonic spelling of the steps in the last mode is somewhat arbitrary. It could be notated as C, D6, E6, F6, G6, A6, B6, C, but reading an F6 in sheet music isn't easy - besides which, this note is functionally the 3rd of a major triad, so why spell it as if it were the 4th?

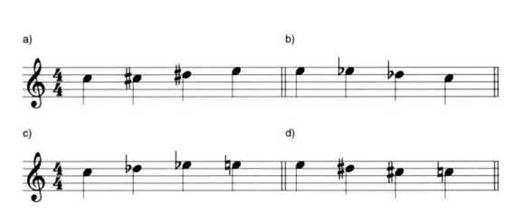

To figure out which mode might be useful with which chord, simply play the chord and then fill in the steps between the chord tones with non-chord tones of one sort or another. At the level where we're operating now, there are no right or wrong choices: It's pretty much up to you to find a mode that you like the sound of. A few options to get you started are shown in Figure 7-24.

Figure 7-24. The modes derived from the ascending melodic minor scale can be used for constructing melodies over certain altered chords. Here are five of the more useful possibilities. If you're a keyboard player, try sustaining each of the chords shown in your left hand while improvising over it in the right hand using the mode shown.

CHROMATIC SPELLING

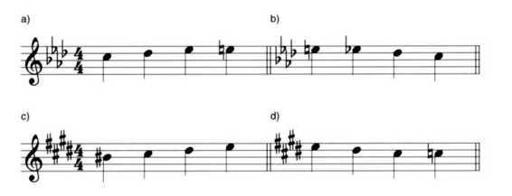

When writing out a passage, especially when it has a number of sharps or flats in the key signature, it's sometimes a bit of a puzzle how to spell a given note. The general rule is that when a line is ascending, accidentals that raise the pitch should be used. When a line is descending, the chromatic spelling should use accidentals that lower the pitch.

There are two reasons for this. First, it's a good idea to spell a scale with consecutive letter-names when possible. For instance, B-C#-D#-E is preferable to B-D6-E6-Eq, even though both spellings contain the same pitches, because B-C-DE is a sensible scale fragment, while B-D-E-E has a skip (from B to D) and a repetition (two E's) in it. The second reason is because when you do it this way, the sheet music will generally require fewer accidentals. Assuming the key signature is C major (no sharps or flats), the line B-C#-D#-E will have two accidentals in it, while B-D6-E6-Eb has three because the flat before the first E has to be cancelled. Figure 7-25 illustrates both of these points.

Figure 7-25. The enharmonic spelling in (a) is preferable to the one in (b), because the motion through a scale by step is clearer, and because fewer accidentals are needed.

This particular scale fragment, which is probably either the lower half of a B major scale or the upper half of an E major scale, would usually be spelled the same whether it was ascending or descending. But if we replace the B with a Ca and then apply the same rules, the simplest spelling will be C-C#-D#-E if we're ascending and E-E6-D6-C if we're descending, as shown in Figure 7-26. In each case, we have a scale fragment (C-D-E or E-D-C) with one repeated letter-name at the beginning. The number of accidentals is kept to a minimum, and the accidentals indicate the direction of the line.

The actual spelling used will, however, be affected by two other factors: the key signature and the harmonic meaning of the individual notes. If the key sig nature is four flats (A6 major), this line would normally be spelled C-D6-E6-Eq even when it's ascending. No accidentals would be needed before the D and E, because they're already flatted in the key signature, so the line could be written with only one accidental (Eb). Using sharps in such a case would violate the rule that the number of accidentals should be kept to a minimum. Conversely, if the key signature has four sharps, the descending line would be spelled either E-D#-C#-Cb or E-D#-C#-B#. In either case, only one accidental (before the last note) would have to be printed. Whether the last note is spelled Cb or B# depends partly on its harmonic meaning. Lacking any other information except the key signature (four sharps), it would be spelled as a B# when the line is ascending, and as a Ca when it's descending, as shown in Figure 7-27. If it's part of a G#7 chord (a V7 of VI in E), it would definitely be spelled as a B#. If it's part of a D7, on the other hand (which is rather far afield in the key of E, but which would be right at home in a jazz chart), it would be spelled as a Cb. These spellings would be used no matter which direction the line was moving.

Figure 7-26. The choice of whether to spell notes enharmonically as sharps or flats often depends on which direction the line is moving. Sharps are more appropriate for ascending lines, and flats for descending lines, because fewer accidentals are needed. The spellings shown in (a) and (b) are preferable to those shown in (c) and (d).

Figure 7-27. The presence of a key signature will sometimes affect how notes in a scale are spelled. The chromatic pitches in this example are the same as those in Figure 7-26, but the spelling will be mostly the same whether the line is ascending or descending.

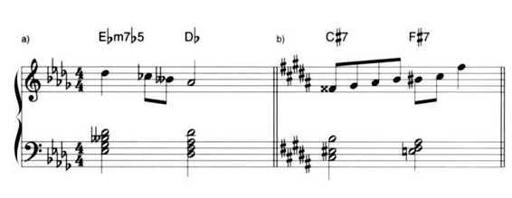

When these rules are applied systematically, notes will occasionally have to be spelled using double-sharps and double-flats, as Figure 7-28 illustrates. Doublesharped and double-flatted notes are hard to sight-read, but keeping the written music theoretically clear usually makes it worthwhile to put up with a bit of awkwardness in reading. On the other hand, there are situations where it's almost a coin-toss how to spell a note within a chord. A classic case is the so-called "German sixth" chord, which we'll meet in Chapter Eight. In 18th- and 19th-century classical music, this chord was normally spelled with an augmented sixth, as shown in Figure 7-29, because the top note resolved by moving upward chromatically. (By the same argument, the 5th of the chord should have been spelled as a doubly augmented 4th - but never mind.) The fact that this chord has the same structure as an ordinary dominant 7th, however, means that the augmented 6th is more naturally spelled as a minor 7th. When it's spelled this way, an extra accidental is needed in the music, as Figure 7-29 makes clear. Even so, the fact that it's easier to read the chord, in combination with the fact that the chord isn't part of the diatonic structure of the key in the first place, has led musicians often to prefer the easier spelling.

Figure 7-28. In order to use the correct enharmonic spelling of notes in keys that have lots of flats or sharps in the key signature, sheet music occasionally has to resort to doubleflats or double-sharps. The A66 in (a) makes both the spelling of the scale fragment (D-CB-A) and the 7th chord (E-G-B-D) clear. The Fx in (b) could perhaps be spelled as a Gb (which would be the flat 5th of the C#7 chord), but the melody can be notated with fewer accidentals when a double-sharp is used. The same argument applies to the B#, by the way.