A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (12 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Figure 3-11. Chord voicings like these, in which two lower voices are in closed position while there's a gap wider than an octave between upper voices, don't tend to sound good.

DOUBLED NOTES & DROPPED NOTES

Up to now we've been looking at voicings consisting of only three notes - one each of the notes in the triad. We can vastly increase our palette of available voicings by doubling selected notes in higher or lower octaves. When it comes to voicings with doubled notes, the only limits are the number of fingers you have available and/or the range of the instrument(s) you're playing. A few useful voicings that employ doubled notes are shown in Figure 3-12. Try out some other possibilities for yourself while sitting at a keyboard.

When choosing which notes to double, you'll probably find that a voicing with several 3rds but only one root and 5th sounds unstable, if not downright unpleasant. The converse is not necessarily true, however. A voicing with only one 3rd and a couple of roots and 5ths will probably sound okay, though it depends on exactly how the notes lie in relation to one another.

Chord voicings will also sound more pleasant or unpleasant, more stable or unstable, depending on how loud various notes within the voicing are in relation to one another. Good pianists will often strike certain keys harder in order to bring out notes within a chord. In a multi-instrument ensemble, the tone colors of the various instruments playing the notes will also affect the desirability of the voicing for a particular musical passage. Pursuing these topics, however, would take us into the realms of instrumental performance and arranging, which are beyond the scope of this book.

Figure 3-12. Some good-sounding voicings of a C major chord in which selected notes are doubled in one or more octaves.

Instead of (or while) doubling certain notes in the chord, we can consider dropping certain notes entirely. Since a triad contains only three distinct notes, doing this will give us a partial, incomplete triad. A partial triad is harmonically ambiguous, as Figure 3-13 demonstrates. In some situations, the ambiguity can be useful: A harmonic ambiguity is a sort of musical pun, because the notes that are played are open to two (or more) different interpretations. In other situations, a partial triad may give the music an unstable or confused sound, which you may not want.

Figure 3-13. When a note is removed from a triad, the two remaining notes are harmonically ambiguous. Is the two-note voicing in (a) C major or C minor? Is (b) C major or A minor? Is (c) C major or E minor? We may be able to tell by listening to what other instruments are playing at the time, but the chord voicing itself doesn't provide enough information.

Dropping selected notes from more complex voicings is often appropriate, as explained in Chapter Six, and doesn't necessarily create any harmonic ambiguity (though it may do so).

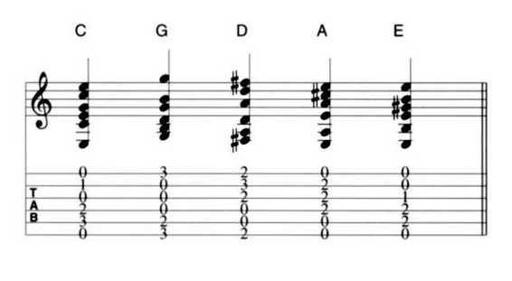

If you're playing guitar, you may not have as much choice as you'd like about which notes to double, or even what inversion of the chord to use. Accomplished guitarists have various tricks for finding good chord voicings. But when you're just starting out, you'll most likely be playing the standard voicings, some of which are shown in Figure 3-14. Only one of these chords (the E major) is voiced in a balanced way. The C and D chords are in first inversion and the A chord is in second inversion. The G chord has a doubled 3rd and only one 5th.

Figure 3-14. The basic chord fingerings on guitar produce the chord voicings shown here. (The F# is often omitted from the low end of the D major chord, because the minor 3rd between the F# and the A produces a somewhat muddy sound.) Note that in sheet music written for guitar, the notes are always shown an octave above the pitches that are actually sounded. This makes it easier to write guitar parts in the treble clef. The chords shown here are notated the way a guitar player would read them; if you play the examples on the piano, they'll sound an octave higher than they would on guitar.

QUIZ

1. What does the abbreviation "aug" in a chord symbol refer to?

2. Name and play the notes in the following triads: E major, B minor, B6 major, A augmented, E6 major, F# minor, G diminished, F diminished, D major.

3. Name and play the notes in the following chords: Dm, F, Adim, B, A6aug, Cm, B6, D6, Gaug, E6m.

4. When the lowest note in a Dm chord voicing is an F, what inversion is the chord in?

5. How many distinct augmented triads are there (considering enharmonic spellings as equivalent)?

6. When a D major chord is played in second inversion, what is the lowest note in the chord voicing?

7 When a D is the lowest note in a B6 chord, what inversion is the chord in?

8. If a chord symbol contains a letter name and a minus sign, what type of triad would you play?

9. In writing an F minor chord for a five-instrument ensemble, which note or notes would you be most likely to double? Which note or notes would you be least likely to double?

10. Explain the difference between open and closed voicings.

4

CHORD

PROGRESSIONS

n the music of some other cultures, it's common for pieces of music to use one chord from start to finish - if, indeed, the music uses structures that are identifiable as chords at all. In music in the European/American tradition, however, pieces that use only one chord are rare. Most pieces make use of at least two or three different chords, which alternate with one another during the course of the piece. Many pieces, even quite short ones, contain upwards of a dozen different chords. By "different," I don't mean different voicings of the same chord, but chords with different roots or of different types.

n the music of some other cultures, it's common for pieces of music to use one chord from start to finish - if, indeed, the music uses structures that are identifiable as chords at all. In music in the European/American tradition, however, pieces that use only one chord are rare. Most pieces make use of at least two or three different chords, which alternate with one another during the course of the piece. Many pieces, even quite short ones, contain upwards of a dozen different chords. By "different," I don't mean different voicings of the same chord, but chords with different roots or of different types.

For the most part, voicings are not shown on lead sheets. Lead sheets will, however, show the types of chords to be used in a piece. They may have different roots, the same root but different 3rds or 5ths (as discussed in Chapter Three), added or altered notes (see Chapters Five and Six), or all of the above.

The order in which the chords occur within the piece is called the chord progression. Chord progressions are among the more interesting phenomena in music. To an untrained listener, a melody is the essence of a popular song - but knowledgeable musicians can identify dozens or hundreds of songs merely by hearing the chord progression alone, without the melody. An unusual or provocative chord progression can turn a simple melody into a moving and unforgettable experience, and an unimaginative or clumsy progression can cripple a great melody. Innumerable standard chord progressions are known by millions of musicians, and can be used as the basis for memorable performances in unrehearsed jam sessions.

It's the nature of a piece of music that has a chord progression that the chord being used changes from time to time. Because of this, the chord progression is sometimes called the chord changes, or simply "the changes" If someone says to you, "Do you know the changes to 'Satin Doll'?", they're talking about the chord progression of the song.

To complete our definition of the term "chord progression," we need to add one more ingredient. A progression is more than a series of chords that occur in a certain order. The chords almost always fall at specific points within a framework of beats and measures. A full discussion of how music is organized rhythmically would be beyond the scope of this book, but the rest of this chapter will make little sense unless you're familiar with the basics, so a brief detour is in order.

MEASURES & BEATS

Music is a time-based art. In order to structure time in a way that will allow music to be played, most forms of music divide time into more or less regular beats. The beat is the pulse of the music - and indeed, the beat will often be at about the same rate as a human pulse, or the rate of footsteps in either walking or running.

Beats are grouped into larger units called bars or measures. The terms "bar" and "measure" are synonymous, with one exception: The vertical line between measures in a piece of sheet music is always called a bar line, never a measure line.

The most common groupings place either three or four beats in each measure. For musicians, these groupings become almost second nature: When you're first learning an instrument, you may have to count "one-two-three-four" in order to learn the rhythm, emphasizing the first beat of each measure as a way of orienting yourself, but by the time you've been playing for a few years, you should be able to count the beats within a measure without ever thinking consciously about it. (As an aside, counting multi-measure rests seems to be difficult for some musicians. I'm not sure why this should be the case, but I suspect it's because they're relying on their intuitive understanding of beats rather than firing up the rational, mathematical part of the brain.)

Other groupings of beats are sometimes heard. Measures consisting of five or seven beats each are difficult for some musicians to play, but their lively, exciting sound makes it worth the effort to learn how to count and play them. In some music, the number of beats per measure changes from time to time. This compositional technique is especially common in post-19th-century classical music. In pop music, the number of beats per measure will usually remain remain the same throughout a given piece.