A History of the World in 100 Objects (34 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

AD

100–500

In the Mexican gallery of the British Museum we have what looks like a giant stone horseshoe – it’s about 40 centimetres (15 inches) long and about 12 centimetres (4 inches) thick, and it is made of a very beautiful grey-green speckled stone. When it first came to the Museum in the 1860s it was thought to be a yoke for something like a carthorse. But there were two immediate problems with this idea: the object is very heavy, nearly 40 kilos (90 lbs), and in any case there were no carthorses or draught animals in Central America until the Spaniards brought them from Europe in the sixteenth century.

It was only just over fifty years ago that it was generally understood that these stone sculptures had nothing to do with animals: they were carvings of objects meant to be worn by men. They represent the padded belts made of cloth or basketwork worn to protect the hips during ancient Central American ball games. Some of these stone ‘belts’ may have been moulds used to shape lighter cloth or leather padding, and the one we have in the Museum is so heavy that if it was worn it can only have been for a very brief time. We don’t know exactly when or how it might originally have been worn; in fact we don’t know if it was meant to be worn at all.

A leading expert on these games, Michael Whittington, thinks these stone belts were primarily for ceremonial use:

Wearing an object that’s 75–100 lbs around your waist during an athletic competition will slow you down considerably, so they were probably worn as part of the ritual ceremonies at the beginning of the game. They do represent the real yokes that were worn during the ball game,

but those real yokes were of perishable materials and they in almost all circumstances have not survived.

We know a little about this Central American ball game because it was quite frequently represented by local artists, who over hundreds of years made sculptures of players and models of pitches with the public sitting on the walls of the court watching the players. Later European visitors wrote accounts the game, and several stadia built specially for it still survive today. When the Spaniards arrived they were amazed by the ball that the game was played with, because it was made of a substance entirely new to Europeans – rubber. The very first view of a bouncing ball, a round object seemingly defying gravity and shooting around in random directions, must have been extremely disconcerting. The Spanish Dominican friar Diego Durán reported a sighting:

They call the material of this ball

hule

[rubber] … jumping and bouncing are its qualities, upward and downward, to and fro. It can exhaust the pursuer running after it before he can catch up with it.

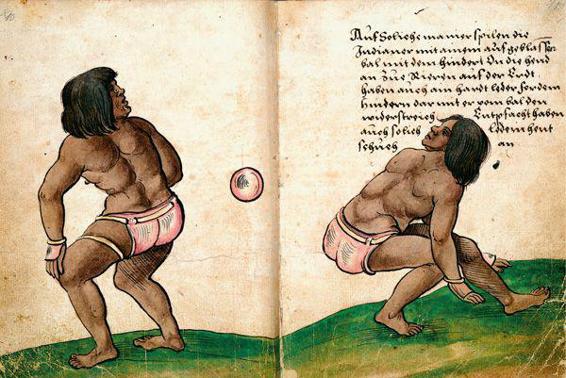

This was not an easy game. The rubber ball was heavy – it could weigh anywhere from 3 or 4 kilos (8 lbs) to almost 15 kilos (30 lbs) – and the aim was to keep it in the air and eventually to land it in the opponents’ end of the court. Players were not allowed to use their hands, head or feet, but had to use their buttocks, forearms and above all their hips – which is where a padded belt would have been most useful. The belts actually used in the game, probably made of leather, wood and woven plants, had to be strong in order to protect the wearer from the heavy ball but light enough to allow him to move about the court. In 1528 the Spanish brought two Aztec players to Europe, and a German artist painted them in mid game, back to back, virtually naked, wearing what look like specially reinforced briefs with the ball in flight between them. The exact rules of the game are unclear and may have changed over the centuries, as well as varying throughout Central America’s different communities. What we do know is that it was played in teams of between two and seven players, and scoring was based on the result of faults, as in tennis today. These faults included touching the ball with a prohibited part of the body such as the head or the hand, failing to return it and sending it out of the court.

The eyes and mouth of the toad on the belt

The balls also became a kind of currency. Spaniards recorded the Aztecs’ exacting tribute payments of 16,000 rubber balls. Not many balls have survived, but excavations and finds made by farmers across Mexico and Central America have turned up a few, as well as hundreds of stone belts like ours and stone reliefs and sculptures showing players with belts around their waists.

By the time our belt was made, around 2,000 years ago, elaborate stone courts built specially for the game were being used. Many were rectangular and several had long sloping walls off which the ball could be bounced. Spectators could also sit along the top of these great stone structures and watch the matches unfold. Clay models show supporters cheering on the players and enjoying the game, just as football fans do today.

But these games were far more than just competitive sports: they held a special place in the belief system of the ancient Central Americans, and our stone belt is a clue to these hidden beliefs. Along the outside of the belt are carved designs, and on the front of the curve of the horseshoe shape, cut into the polished stone, is the stylized image of a toad. He has a broad mouth stretching the whole length of the curve and, behind the eyes, bulbous glands which extend back to the crouched hind legs. Zoologists have been able to identify the species as the Giant Mexican Toad (

Bufo marinus

). Perhaps the key to understanding this object is that this toad excretes a hallucinogenic substance, and Central Americans believed that it represented an Earth goddess. Belts for ball games were made with various underworld animals carved into them, and this tells us that they were meant to be viewed not individually but rather as part of a broader ritual. It seems that the painful intensity of the ball game symbolized the constant cosmic struggle between the forces of life and death. Michael Whittington elaborates:

I think it’s a metaphor for how Meso-Americans view the world. When you look at one of the great creation stories in Meso-America, the Popol Vuh, there are twins. Their names were Xbalanque and Hunahpuh. They were ball players, they lived in the underworld, and they played ball with the lords of death. The game re-emphasized how Meso-Americans viewed themselves in the cosmos and in relation to the gods. So they were playing out a game of gods and the lords of death every time they took to the ball court.

This is disconcertingly familiar. Whether it’s Maradona’s infamous ‘hand of God’, which he claimed scored his first goal in Argentina’s match against England in the 1986 World Cup, the carrying of the flame from the sanctuary at Olympia in Greece at the start of each Olympic Games, or Welsh rugby fans singing hymns at Cardiff Arms Park, competitive sport and religion seem often to be closely related. Few supporters today, singing hymns or cheering for their teams with fanatical enthusiasm, know that the world’s earliest known team sport also had a strong religious dimension or that the story began not in ancient Greece but in Central America.

But modern sportsmen don’t face the hazards of their predecessors. It used to be thought that the losing team was always sacrificially slaughtered, and, though this did occasionally happen later, at the time of our belt we don’t know what lay in store for the losers. Mostly the games were an opportunity for a community to feast, to worship, and to create and reaffirm social ties. It’s thought that early on this was a game that both men and women could play, but by the time the Spanish encountered the Aztecs in the sixteenth century it was being played exclusively by men. The ball courts were designed to be sacred spaces in which offerings were buried, so making the building itself a living entity. The Spanish recognized the religious significance of the courts and wanted to replace the old local pagan religion with their new Catholic one. It is no accident that they built their cathedral in what is today Mexico City on the site of the Great Ball Court of the ancient Aztec city Tenochtitlán. But, although the courts were destroyed or abandoned, the game survived the brutal conquest of Mexico and the destruction of Aztec culture. A form of it, called

ulama,

is even played today – proof, if any was needed, that once a sport embodies a national identity as this one does, it has enormous staying power.

Christoph Weiditz’s drawing of Central American ballplayers at the court of Emperor Charles V

The annotation on the drawing above reads:

‘In such manner the Indians play with the blown-up ball with the seat without moving their hands from the ground; they have also a hard leather before their seat in order that it shall receive the blow from the ball, they have also such leather gloves on.’

One of the striking characteristics of organized games throughout history is their capacity to transcend cultural differences, social divisions and even political unrest. Straddling the boundary between the sacred and the profane, they can be great social unifiers and dividers. There are few other things that we collectively care about so much in our society today. Our Mexican ceremonial belt acts as a powerful symbol of how far all societies can take their delight in mass, organized sport.

The emperor turns to reject his wife.

The verse in the illustration above reads:

No one can please forever; / Affection cannot be for one alone; / If it be so, it will end in disgust. / When love has reached its highest pitch, it changes its object; / For whatever has reached fullness must decline. / This law is absolute. / The ‘beautiful wife who knew herself to be beautiful’ / Was soon hated. / If by a mincing air you seek to please, / Wise men will abhor you. / From this cause truly comes / The breaking of favour’s bond.

Admonitions Scroll

AD

500–800

After banqueting and gay sex in the early Roman Empire, smoking and ceremony in North America, ball games and belief in Mexico, we come to another kind of elaborate social pleasure – looking at painting. Specifically I want to look at a masterpiece of painting from China, in the form of a scroll, based on an original painted around the years

AD

400 or 500. It embraces three separate art forms, in China known lyrically as ‘the three perfections’: painting, poetry and calligraphy. As a handscroll it was made to be viewed with selected friends, and as a fine work of art it was cherished by emperors over hundreds of years. It’s known as

The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies

, or the

Admonitions Scroll

, for short, and it’s a form of ancient guide to manners, and above all to morals, for ladies of the Chinese court – it tells powerful women how to behave.