A History of the World in 100 Objects (32 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

It was a cult sustained by constant propaganda. All across Europe, towns were named after him. The modern Zaragoza is the city of Caesar Augustus, while Augsburg, Autun and Aosta all derive from Augustus. His head was on coins – and everywhere there were statues. But the British Museum’s head is a head from no ordinary statue. It takes us into another story – one that shows a darker side of the imperial narrative, for it tells us not only of Rome’s might, but of the problems that threatened and occasionally overwhelmed it.

This head was once part of a complete statue that stood on Rome’s most southerly frontier, on the border between modern Egypt and Sudan – probably in the town of Syene, near Aswan. This region has always been a geopolitical faultline, where the Mediterranean world clashes with Africa. In 25

BC

, so the writer Strabo tells us, an invading army from the Sudanese kingdom of Meroë, led by the fierce one-eyed queen Candace, captured a series of Roman forts and towns in southern Egypt. Candace and her army took our statue back to the city of Meroë and buried the severed head of the glorious Augustus beneath the steps of a temple dedicated to victory. It was a superbly calculated insult. From now on, everybody walking up the steps and into the temple would literally be crushing the Roman Emperor under their feet. And if you look closely at the head you can see tiny grains of sand from the African desert embedded in the surface of the bronze – a badge of shame still visible on the glory of Rome.

But there was further humiliation to come. The indomitable Candace sent ambassadors to negotiate the terms of a peace settlement. The case ended up before Augustus himself, who granted the ambassadors pretty much everything they asked for. He secured the Pax Romana, but at a considerable price. It was the action of a shrewd, calculating political operator, who then used the official Roman propaganda machine to airbrush this setback out of the picture.

Augustus’s career became the imperial blueprint of how to achieve and retain power. A key part of retaining power was the management of his image. Susan Walker describes that image:

Apart from presenting himself in images exactly as he did on the day that he became ‘Augustus’, he presented himself very modestly. He often showed himself wearing the Roman toga, drawn over his head to show piety. And sometimes he was shown as a general leading his troops into battle, even though he never actually did so. We have more than 250 images of Augustus which come from all over the Roman Empire, and they are pretty much the same – the portrait was very recognizable, and very enduring.

This eternal image would be coupled with an eternal name. After his death, Augustus was declared a god by the Senate, to be worshipped by the Romans. His titles Augustus and Caesar were adopted by every subsequent emperor, and the month of Sextilius was officially renamed August in his honour. Boris Johnson comments:

Augustus was the first emperor of Rome and he created from the Roman Republic an institution that, in many ways, everybody has tried to imitate in the succeeding centuries. If you think about the tsars, the kaiser, the tsars of Bulgaria, Mussolini, Hitler and Napoleon, all of them have tried to imitate that Roman iconography, that Roman approach, a great part of which began with Augustus and the first ‘principate’, as it was called, the first imperial role that he occupied.

Great leaders like Augustus create great empires, but within those empires people are governed by the same passions, pastimes and appetites that have always governed more ordinary people’s lives. It was no different under the Pax Romana. The next few objects, all from the time of the Pax Romana, provide insights into those lives. They deal with vices, and spices. And we begin with a silver cup made for a pederast in Palestine.

Ancient Pleasures, Modern Spice

AD

1–500

The objects in this section all show how attitudes to pleasure, luxury and leisure fluctuate throughout history – for example the relationships between boys and older men tolerated in the Roman Empire would be illegal today. This section also shows how many of our modern pleasures and leisure activities have their origins in ancient religion: tobacco smoking and some of the earliest team sports were elements in elaborate rituals when they are first countered, in the Americas. In the Roman empire, pepper became a marker not just of wealth, but of ostentatious refinement that some feared would bankrupt the state. In China a painting carried on its surface the record of those who over generations enjoyed its rarified message of how a lady should behave.

Warren Cup

AD

5–15

Two thousand years ago, the elite members of great empires like that of Rome were not solely concerned with power and conquest. Like all elites they also found time for pleasure, and art. This object incorporates both. It is a silver cup made in Palestine, in about

AD

10. Before coming to the British Museum it had been in the collection of the wealthy American Edward Warren (who commissioned the most famous version of Rodin’s sculpture

The Kiss

), and it tells us almost as much about twentieth-century attitudes to sex as about Roman ones.

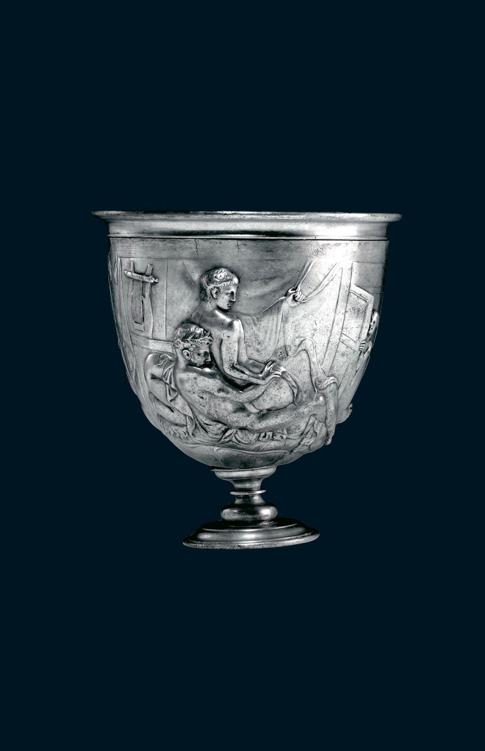

The Warren Cup shows scenes of sexual coupling between adult men and adolescent boys. This 2,000-year-old piece of Roman silverware is a goblet that looks as though it would hold a pretty large glass of wine. It’s in the shape of a modern sporting trophy, standing on a small base, and it would once have had two handles, though these are now lost. You can see at once that this is a work of supreme craftsmanship. The scenes on the cup are in relief, created by beating out the silver from the inside. It must have been used at private parties, and given the subject matter it would certainly have commanded the admiration and the attention of everybody present.

Lavish eating and drinking were among the key rituals of the Roman world. Throughout the empire, Roman officials and local bigwigs would use banquets to oil the wheels of politics and business and show off wealth and status. Roman women were generally excluded from events such as the drinking parties where our cup would have been found, and we can probably assume that it was intended for a party with an all-male guest list.

Imagine a man arriving at a grand villa near Jerusalem somewhere

around the year 10. Slaves lead him through to an opulent dining area, where he reclines with the other guests. The table is laid with silver platters and ornate vessels. This is the context in which our cup would have been passed around among the guests. On it two scenes of male love-making are set in a sumptuous private house. The lovers are depicted on draped couches similar to the ones the guests at our imaginary dinner party would be lounging on. And you can see a lyre and pipes waiting to be played as the participants settle to their sensual pleasures. The Classical historian and broadcaster Bettany Hughes elaborates:

The cup depicts two varieties of a homosexual act. On the front there is an older man – we know he’s older because he has a beard; sitting astride him is a very handsome young man. It’s all very vigorous and virile, very realistic – it isn’t an idealized view of homosexuality. But if you look round the back there is a more standard portrayal of homosexuality. It shows two very beautiful young men – we know that they’re young because they have locks of hair hanging down their backs. One is lying on his back, and the slightly older man is looking away. It’s a lot more lyrical, a rather idealized view of what homosexuality was

.

Although the homosexual scenes on the cup are ones that today strike us as explicit – some might say shocking and taboo – homosexuality was very much part of Roman life. But it was a complicated part, tolerated but not entirely accepted. The standard Roman line on what was admissible in same-sex coupling is neatly summarized by the Roman playwright Plautus in his comedy

Curculio

: ‘Love whatever you wish, as long as you stay away from married women, widows, virgins, young men and free boys.’

The other side of the cup shows two youths

So if you wanted to show sex between men and youths who weren’t slaves, it made sense to look back to the age of Classical Greece, where it was normal for older men to teach younger boys about life in general, in a mentoring relationship that included sex. The early Roman Empire had idealized Greece and adopted much of its culture, and the cup shows what is clearly a Greek scene. Is this a Roman sexual fantasy of a Classical Greek male coupling? Perhaps by placing it in a Greek past any moral discomfort is put at a safe distance, while adding to the titillation of the forbidden and exotic. And perhaps everybody believes that the best sex happens somewhere else. Professor James Davidson, author of

The Greeks and Greek Love

, explains:

Although this cup looks back to the Classical period, the Greek vase painters, who were by no means prudish or modest when it came to depicting sex, nevertheless carefully avoided scenes of homosexual intercourse, at least penetrative intercourse. So the Romans are showing what couldn’t be shown 500 years earlier. The Greek world provided an alibi that allowed societies to think about homosexuality, to talk about homosexuality, to represent homosexuality, as it did from the eighteenth century onwards and even in the Middle Ages. It made it into a piece of art more than a piece of pornography.

There’s no doubt where these encounters are taking place. The musical instruments, the furniture, the clothes and the hairstyles of the lovers all point to the past – to the Classical Greece of several centuries earlier. Interestingly, we can tell from our cup that the two younger adolescents shown here were not slaves. The style of their haircuts, with a long lock trailing down the neck, is typical of freeborn Greek boys. Between 16 and 18, the hair would be cut and dedicated to the gods as part of the passage into manhood. So both the boys shown on the cup are free and from good families. But we can also see another figure, who might have been part of the Roman banquet at which the cup was used. He stands in the background, peeping at one of the scenes of love-making from behind a door – we only see half his face. He is clearly a slave, although it is impossible to know whether he is simply indulging in a bit of voyeurism or apprehensively responding to a call for ‘room service’. Either way, he’s a reminder that what he and we are witnessing are acts to be conducted only in private behind closed doors. Bettany Hughes comments:

In Rome there was a notion that you have good wives and that you should manage without resorting to male sex. But we know, from the poetry, from the laws, from the back-references to homosexual relations, that actually this was something that did happen throughout the Roman world. The Warren Cup is a good bit of exquisite hard evidence which proves that. This cup is telling us what actually went on, how homosexual activity was something which took place in high aristocratic circles.