A History of the World in 100 Objects (36 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

When the Romans came to Britain they brought a lot of material culture and a lot of habits with them that made the people of Britain feel Roman; they identified with the Roman culture. Wine was one of these – olive oil was another – and pepper would have been a more valuable one in this same sort of ‘set’ of Romanitas.

The Romans were particularly serious about their food. Slave chefs would man the kitchens to create great delicacies for their consumption. A high-end menu could include dormice sprinkled with honey and poppy seeds, then a whole wild boar being suckled by piglets made of cake, in which were placed live thrushes, and to finish, quince, apples and pork disguised as fowls and fish. None of these opulent culinary inventions would have been created without ample seasoning – and the primary spice would have been pepper.

Why has this particular spice remained so constantly attractive for us? I asked the author Christine McFadden about the importance of a bit of pepper in your recipe:

They just couldn’t get enough of it. Wars were fought over it, and if you look at Roman recipes, every one starts with ‘take pepper and mix with …’.

An early twentieth-century chef said that no other spice can do so much for so many different types of food, both sweet and savoury. It contains an alkaloid called piperine, which is responsible for the pungency. It promotes sweating, which cools the body – essential for comfort in hot climates. It also aids digestion, titillates the taste buds and makes the mouth water.

The closest place to Rome where pepper actually grew was India, so the Romans had to find a way of sending ships to and fro across the Indian Ocean and then carrying their cargo overland to the Mediterranean. Whole fleets and caravans laden with pepper would travel from India to the Red Sea, then across the desert to the Nile. It was then traded around the Roman Empire by river, sea and road. This was an immense network, complicated and dangerous, but highly profitable. Roberta Tomber fills in the details:

Strabo in the first century

AD

says that 120 boats left every year from Myos Hormos – a port on the Red Sea – to India. Of course, there were other ports on the Red Sea and other countries sending ships to India. The actual value of the trade was enormous – one hint we have of this is from a second-century papyrus known as the Muziris Papyrus. In that they discuss the cost of a shipload estimated today at 7 million sestertia. At that same time a soldier in the Roman army would have earned about 800 sestertia a year

.

Regularly filling a single large silver pepper pot like ours would therefore have taken a big chunk out of the grocery budget, yet the household that owned our pepper pot had another three silver pots, for pepper or other spices – one shaped as Hercules in action and two in the shapes of animals. This is dizzying extravagance. But the pepper pots are just a tiny part of the great hoard of buried treasure. They were found in a chest containing seventy-eight spoons, twenty ladles, twenty-nine pieces of spectacular gold jewellery, and more than 15,000 gold and silver coins. Fifteen different emperors are represented on the coins; the latest is Constantine III, who came to power in 407. This helps us to date the hoard, which must have been buried for safekeeping some time after that year – when Roman authority in Britain was rapidly breaking down.

This brings us back to our pepper pot in the shape of a high-born Roman matron. With her right forefinger she points to a scroll, which she holds proudly, rather like a graduate showing off a degree certificate in a graduation photograph. This tells us that the woman is not only from a wealthy family but that she was also educated. Although Roman women were not allowed to practise professions such as law or politics, they were taught to be accomplished in the arts. Singing, playing instruments, reading, writing and drawing were all talents expected of a well-bred lady. And, while a woman like this could not hold public office, she would certainly have been in a position to exercise power.

We don’t know who this woman was, but there are clues to be found on other objects from the hoard – a gold bracelet is inscribed

UTERE FELIX DOMINA IULIANE

, meaning ‘Use this happily, Lady Juliane’

.

We will never know if this is the lady on our pepper pot, but she may well have been its owner. Another name, Aurelius Ursicinus,

is found on several of the other objects – could this have been Juliane’s husband? All the objects are small but extremely precious. This was the mobile wealth of a rich Roman family – precisely the type of person who is in danger when the state fails. There were no Swiss bank accounts in the ancient world – the only thing to do was bury your treasure and hope that you lived to come back and find it. But Juliane and Aurelius never did come back and the buried treasure remained in the ground. That is, until 1,600 years later, when in 1992 a farmer, Eric Lawes, went to look for a missing hammer. What he found, with the help of his metal detector, was this spectacular hoard. And he found the hammer too – which is now also part of the British Museum’s collection.

Many of the objects in this history would mean little to us were it not for the work of thousands of people – archaeologists, anthropologists, historians and numerous others – and we wouldn’t even have found many of these objects without metal detectorists like Eric Lawes, who in recent years have been rewriting the history of Britain. When he found the first few objects he alerted local archaeologists so that they could record the detail of the site and lift the hoard out in blocks of earth. Weeks of careful micro-excavation in the laboratories of the British Museum revealed not only the objects but the way in which they were packed. Although their original container, a wooden chest about 60 centimetres (2 feet) wide, had largely perished, its contents remained in their original positions. Our pepper pot was buried alongside a stack of ladles, some small silver jugs and a beautiful silver handle in the shape of a prancing tigress. Right at the top, lovingly wrapped in cloth, were necklaces, rings and gold chains, placed there by people uncertain of when or whether they would ever wear them again. These are objects that bring us very close to the terrifying events that must have been overwhelming these people’s lives.

Written on one of the spoons in the hoard is

VIVAS IN DEO

(‘May you live in God’) – a common Christian prayer – and it is likely that our fleeing family was Christian. By this date Christianity had been the official religion of the Empire for nearly a hundred years. Like pepper, it had come to Britain via Rome, and both survived the fall of the Roman Empire.

The Rise of World Faiths

AD

100–600

Striving to comprehend the infinite, a small number of major faiths have shaped the world over the last 2,000 years. Strikingly, the defining representational traditions of Buddhism, Christianity and Hinduism all developed within a few hundred years of each other: Buddhism first began to allow images of the Buddha in human form from

AD

100 to 200, and the oldest images of Jesus Christ coincide with the acceptance of Christianity as the predominant religion of the Roman Empire in

AD

312. At a similar time, Hinduism established the conventions for depicting its gods that are still familiar today. In Iran, Zoroastrianism, the state religion, articulated the ritual duties of the ruler to secure order in the world. The birth of the Prophet Muhammad in

AD

570 set the scene for the rise of Islam, which eventually overwhelmed the many local gods who had been worshipped in Arabia.

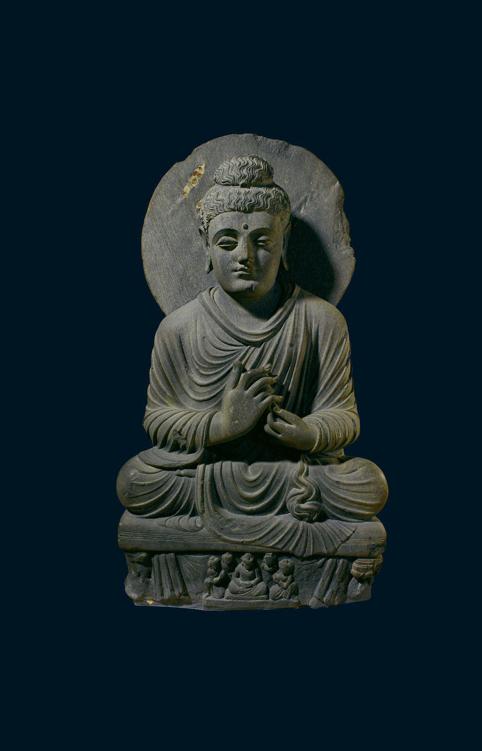

Seated Buddha from Gandhara

100–300

AD

Battersea Park in London, just south of the Thames, isn’t the obvious place to encounter the Buddha. But there, next to the Peace Pagoda, a Japanese Buddhist monk, watched by four gilded Buddha statues, drums his way over the grass each day. His name is the Reverend Gyoro Nagase, and he knows these gilded Buddhas very well. But then in a sense so do we all: here, looking out over the Thames, is the Buddha sitting cross-legged, his hands touching in front of his chest. I hardly need to describe the figure any further, because the seated Buddha is one of the most familiar and most enduring images in world religion.

In the British Museum we have a Buddha sculpture carved from grey schist, a rock that contains fragments of crystal which make the stone glint and gleam in the light. The Buddha’s hands and face are more or less life-size, but the body is smaller, and he sits cross-legged in the lotus position, with his hands raised in front of him. On both shoulders he wears an over-robe, and the folds of the drapery form thick, rounded ridges and terraces. This drapery hides most of his feet, except for a couple of the toes on the upturned right foot, which you can just see. His hair is gathered up into what seems to be a bun but which is in fact a symbol of the Buddha’s wisdom and enlightened state. He looks serenely into the distance, his eyelids lowered. And rising from the top of his shoulders, surrounding his head, is what looks like a large grey dinner plate – but of course it is his halo.

Today, you can find statues of the Buddha, seated and serene, all over the world. But the Buddha hasn’t always been there for us to contemplate. For centuries he was represented only through a set of symbols. The story of how this changed, and how the Buddha came to be shown in human form, begins in Pakistan around 1,800 years ago.

By that time Buddhism had already been in existence for centuries. According to Buddhist tradition, the historical Buddha was a prince of the Ganges region in north India in the fifth century

BC

who abandoned his royal life to become a wandering ascetic, wanting to comprehend and therefore to overcome the roots of human suffering. After many experiences he finally sat under a pipal tree and meditated without moving for forty-nine days until, at last, he achieved enlightenment – freedom from greed, hate and delusion. At this moment he became the Buddha – the ‘Enlightened’ or the ‘Awakened One’. He passed on his

dharma

– his teaching, his way – to monks and missionaries who eventually travelled across vast expanses of Asia. As the Buddhist message spread north, it passed into the region known as Gandhara, in what is now north-eastern Pakistan, around Peshawar in the foothills of the Himalayas.

All religions have to confront the key question – how can the infinite, the boundless, be apprehended? How can we humans draw near to the other, to god? Some aim to achieve this through chanting, some through words alone, but most religions have found images useful for focusing human attention on the divine. A little under 2,000 years ago, this tendency strikingly gained impetus among a number of great religions. Is it more than an extraordinary coincidence that at about the same moment Christianity, Hinduism and Buddhism first start showing Christ, Hindu gods and the Buddha in human form? Coincidence or not, it is at this point that all three religions established artistic conventions which are still very much alive today.

In Gandhara, from the 1850s onwards, large numbers of Buddhist shrines and sculptures were discovered and investigated – in fact more Buddhist sculpture and architecture comes from Gandhara than from any other part of ancient India. Our virtually life-size and lifelike figure is one of these. It must have been a startling sight for any Buddhist 1,800 years ago. Until shortly before then the Buddha had been represented only by sets of symbols – the tree under which he achieved enlightenment, a pair of footprints, and so on. To give him human form was entirely new.

The move towards representing Buddha as a man is described by the historian Claudine Bautze-Picron, who teaches Indian art history at the Free University of Brussels:

The Buddha was a real historical character, so he was not a god. There was a movement 2,000 years or so ago when they started representing various deities and human wise men who had lived a few hundred years before. The first evocation of the Buddha’s presence is carved around the circular monuments called stupas. There the Buddha is referred to through the tree below which he sat, where he became awakened, which is in fact the meaning of ‘Buddha’ – to be awakened. The worship of footprints is a major element in India still today; they refer to a person who is no longer there but who has left traces on Earth. This developed towards an even more elaborated structure, where you have a flaming pillar in place of the tree, which means that light emerges out of the Buddha. So there were symbols which were creeping in to the artistic world and which really opened the way to the physical image of the Buddha.