A History of the World in 100 Objects (29 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Pillar of Ashoka

AROUND

238

BC

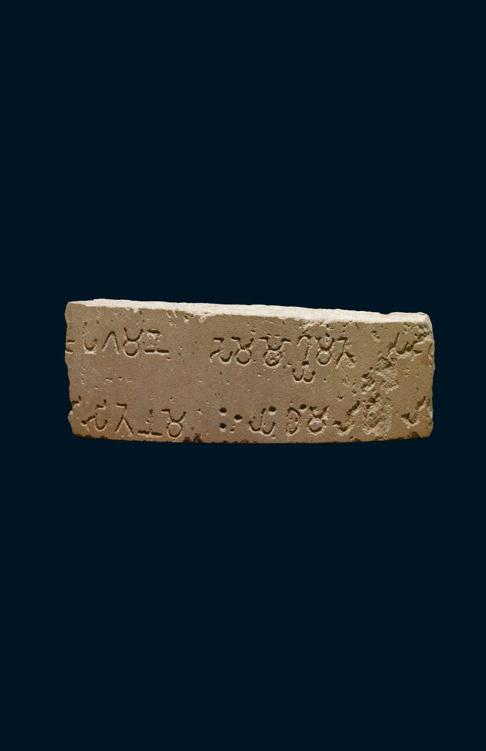

Around 2,000 years ago the great powers of Europe and Asia established legacies that are still with us. They laid down the fundamental ideas concerning the right way for a leader to rule, how rulers construct their image and how they project their power. They also showed that a ruler can actually change the way the people think. The Indian leader Ashoka the Great took over a vast empire and, through the strength of his ideas, began a tradition that leads directly to the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi and still flourishes today – a tradition of pluralistic, humane, non-violent statecraft. Those ideas are incorporated in this object. It’s a fragment of stone, sandstone to be exact, and it’s about the size of a large curved brick – not much to look at all, but it opens up the story of one of the great figures of world history. On the stone are two lines of text, inscribed in round, spindly-looking letters – once described as ‘pin-man script’. These two lines are the remains of a much longer text that was originally carved on a great circular column, about 9 metres (30 feet) high and just under a metre (3 feet) in diameter.

Ashoka had pillars like this put up across the whole of his empire. They were great feats of architecture, which stood by the side of highways or in city centres – much as public sculpture does in our city squares today. But these pillars are different from the Classical columns that most of us in Europe are familiar with: they’ve got no base and they’re crowned with a capital in the shape of lotus petals. On top of the most famous of Ashoka’s pillars are four lions facing outwards – lions that are still one of the emblems of India today. The pillar that our fragment comes from was originally erected in Meerut, a city just north of Delhi, and was destroyed at the palace of a Mughal ruler by an explosion in the early eighteenth century. But many similar pillars have survived, and they range across Ashoka’s empire, which covered the great bulk of the subcontinent.

These pillars were a sort of public-address system. Their purpose was to carry, carved on them, proclamations or edicts from Ashoka, which could then be promulgated all over India and beyond. We now know that there are seven major edicts that were carved on pillars, and our fragment is from what’s known as the ‘sixth pillar edict’; it declares the emperor Ashoka’s benevolent policy towards every sect and every class in his empire:

I consider how I may bring happiness to the people, not only to relatives of mine or residents of my capital city, but also to those who are far removed from me. I act in the same manner with respect to all. I am concerned similarly with all classes. Moreover, I have honoured all religious sects with various offerings. But I consider it my principal duty to visit the people personally.

There must have been somebody to read these words out to the mostly illiterate citizens, who would probably have received them not only with pleasure but with considerable relief, for Ashoka had not always been so concerned for their welfare. He’d started out not as a gentle and generous philosopher but as a ruthless and brutal youth, following in the military footsteps of his grandfather, Chandragupta, who had risen to the throne following a military campaign that created a huge empire reaching from Kandahar in modern Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh in the east. This included the great majority of modern India, and was the largest empire in Indian history.

In 268

BC

Ashoka took his place on the throne – but not without considerable struggle. Buddhist writings tell us that in order to do so he killed ‘ninety-nine of his brothers’ – presumably metaphorical as well as actual brothers. The same writings create a legend of Ashoka’s pre-Buddhist days as filled with self-indulgent frivolity and cruelty. When he became emperor he set out to complete the occupation of the whole subcontinent and attacked the independent state of Kalinga – modern-day Orissa on the east coast. It was a savage, brutal assault and one which seems afterwards to have thrown Ashoka into a state of terrible remorse. He changed his whole way of life, embracing the defining concept of

Dharma

, a virtuous path that guides the follower through a life of selflessness, piety, duty, good conduct and decency.

Dharma

is applied in many religions, including Sikhism, Jainism and of course Hinduism – but Ashoka’s idea of

Dharma

was filtered through the Buddhist faith. He described his remorse and announced his conversion to his people through an edict:

The Kalinga country was conquered by the king, Beloved of the Gods, in the eighth year of his reign. 150,000 persons were carried away captive, 100,000 were slain, and many times that number died. Immediately after the Kalingas had been conquered, the king became intensely devoted to the study of

Dharma

…The Beloved of the Gods, conqueror of the Kalingas, is moved to remorse now. For he has felt profound sorrow and regret because the conquest of a people previously unconquered involves slaughter, death and deportation.

From then on Ashoka set out to redeem himself – to reach out to his people. To do so, he wrote his edicts not in Sanskrit, the ancient Classical language that would later become the official language of the state, but in the appropriate local dialect couched in everyday speech

.

With his conversion Ashoka renounced war as an instrument of state policy and adopted human benevolence as the solution to the world’s problems. While he was inspired by the teachings of Buddha – and his son was the first Buddhist missionary to Sri Lanka – he did not impose Buddhism on his empire. Ashoka’s state was in a very particular sense a secular one. The Nobel Prize-winning Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen comments:

The state has to keep a distance from all religion. Buddhism doesn’t become an official religion. All other religions have to be tolerated and treated with respect. So secularism in the Indian form means not ‘no religion in government matters’, but ‘no favouritism of any religion over any other’.

Religious freedom, conquest of self, the need for all citizens and leaders to listen to others and to debate ideas, human rights for all, both men and women, and the importance given to education and health, the ideas Ashoka promulgated in his empire, all remain central in Buddhist thinking. There’s still today a kingdom in the Indian sub-continent that is run on Buddhist principles – the small Kingdom of Bhutan, sandwiched between northern India and China. Michael Rutland is a Bhutanese citizen and the Hon. Consul of Bhutan to the UK. He also tutored the former king, and I asked him how Ashoka’s ideas might play out in a modern Buddhist state. He began by offering me a quotation:

‘Throughout my reign I will never rule you as a king. I will protect you as a parent, care for you as a brother and serve you as a son.’ That could well have been written by the emperor Ashoka. But it wasn’t. It was an excerpt from the coronation speech, in 2008, of the 27-year-old fifth king of Bhutan. The fourth king, the king that I had the great privilege to teach, lived and continues to live in a small log cabin. There is no ostentation to the monarchy. He is probably the only example of an absolute monarch who has voluntarily persuaded his people to take away his powers and has instituted elective democracy. The fourth king also introduced the phrase ‘gross national happiness’ – to be a contrast to the concept of ‘gross national product’. Again, as Ashoka would have felt, the happiness and contentment of the people were more important than conquering other lands. The fifth king has very much followed the Buddhist precepts of monarchy.

Ashoka’s political and moral philosophy, as he expressed it in his imperial inscriptions, initiated a tradition of religious tolerance, non-violent debate and a commitment to the idea of happiness which has animated Indian political philosophy ever since. But – and it’s a big but – his benevolent empire scarcely outlived him. And that leaves us with the uncomfortable question of whether such high ideals can survive the realities of political power. Nevertheless, this was a ruler who really did change the way that his subjects and their successors thought. Gandhi was an admirer, as was Nehru, and Ashoka’s message even finds its way on to the modern currency – on all Indian banknotes we see Gandhi facing the four lions of Ashoka’s pillar. The architects of Indian independence had him often in mind. But, as Amartya Sen points out, his influence extends far wider, and the whole region sees him as an inspiration and a model:

The part of his teaching that the Indians particularly empathized with at the time of independence was his secularism and democracy. But Ashoka is also a big figure in China, in Japan, in Korea, in Thailand, in Sri Lanka; he is a pan-Asian figure.

My next object involves another kind of inscription and another ruler closely linked with a religious system, but in this case the religion is now dead and the ruler is no longer of any consequence – indeed he never really was. The inscription is one of the most famous objects in the British Museum – and possibly the world.

Rosetta Stone

196

BC

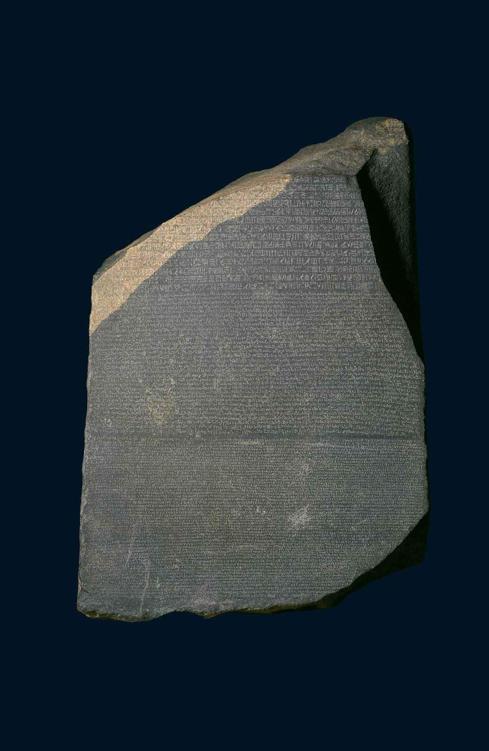

Every day when I walk through the Egyptian sculpture gallery at the British Museum there are tour guides speaking every imaginable language addressing groups of visitors, all craning to see this object. It is on every visitor’s itinerary, and, with the mummies, it’s the most popular object in the British Museum. Why? It’s decidedly dull to look at – a grey stone about the size of one of those large suitcases you see people trundling around on wheels at airports. The rough edges show that it’s been broken from a larger stone, with the fractures cutting across the text that covers one side. And when you read that text, it’s pretty dull too – it’s mostly bureaucratic jargon about tax concessions. But, as so often in the Museum, appearances are deceptive. This dreary bit of broken granite has played a starring role in three fascinating and different stories: the story of the Greek kings who ruled in Alexandria after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt; the story of the French and British imperial competition across the Middle East after Napoleon invaded Egypt; and the extraordinary but peaceful scholarly contest that led to the most famous decipherment in history – the cracking of hieroglyphics.

The Rosetta Stone is a particularly fascinating and special case of power projection. It’s associated with a ruler who was not strong but weak, a king who had to bargain for and protect his power by borrowing the invincible strength of the gods or, more precisely, the priests. He was Ptolemy V, a Greek boy-king who came to the throne of Egypt as an orphan in 205

BC

, at the age of 6.

Ptolemy V was born into a great dynasty. The first Ptolemy was one of Alexander the Great’s generals who, around a hundred years earlier, had taken over Egypt following Alexander’s death. The Ptolemies didn’t trouble to learn Egyptian but made all their officials speak Greek; so Greek became the language of state administration in Egypt for a thousand years. Perhaps their greatest achievement was to make their capital city, Alexandria, into the most brilliant metropolis of the Classical world – for centuries it was second only to Rome, and intellectually probably livelier. It was a cosmopolitan magnet for goods, people and ideas. The vast Library of Alexandria was built by the Ptolemies – in it, they planned to collect all the world’s knowledge. And Ptolemies I and II created the famous Pharos lighthouse, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Such a lively, diverse city needed strong leadership. When Ptolemy V’s father died suddenly, leaving the boy as king, the dynasty and its control of Egypt looked fragile. The boy’s mother was killed, the palace was stormed by soldiers and there were revolts throughout the country that delayed the young Ptolemy’s coronation for years.