A History of the World in 100 Objects (30 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

It was in these volatile circumstances that Ptolemy V issued the Rosetta Stone, and others like it. The stone is not unique; there are another seventeen similar inscriptions quite like it that have survived, all in three languages and each proclaiming the greatness of the Ptolemies. They were put up in major temple complexes across Egypt. The Rosetta Stone itself was made in 196

BC

, on the first anniversary of the coronation of Ptolemy V, by then a teenager. It’s a decree issued by Egyptian priests, ostensibly to mark the coronation and to declare Ptolemy’s new status as a living god – divinity went with the job of being a pharaoh. The priests had given him a full Egyptian coronation at the sacred city of Memphis, and this greatly strengthened his position as the rightful ruler of the country. But there was a trade-off. Ptolemy may have become a god, but to get there he had to negotiate some very unheavenly politics with his extremely powerful Egyptian priests. Dr Dorothy Thompson, of Cambridge University, explains:

The occasion which resulted in this decree was in some respects a change. There had been previous decrees, and they take much the same form, but in this particular reign a very young king was under attack from many quarters. One of the clauses of the Memphis decree, the Rosetta Stone, is that priests should no longer come every year to Alexandria, the new Greek capital; instead they could meet at Memphis, the old centre of Egypt. This was new, and it may be seen as a concession on the part of the royal household.

The priests were critical in keeping the hearts and minds of the Egyptian masses onside for Ptolemy, and the promise inscribed on the Rosetta Stone was their reward. Not only does the decree allow the priests to remain in Memphis, rather than coming to Alexandria, it also gives them some very attractive tax breaks. No teenager is likely to have thought this up, so somebody behind the throne was thinking strategically on the boy’s behalf and, more importantly, on the dynasty’s behalf.

The Rosetta Stone is therefore simultaneously an expression of power and of compromise, though to read the whole content is about as thrilling as reading a new EU regulation written in several languages. It is bureaucratic, priestly and dry.

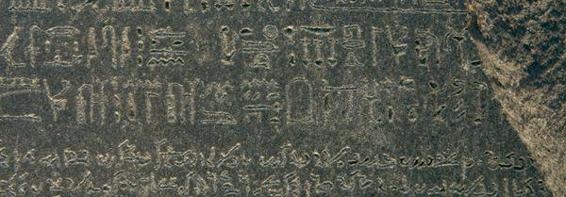

What matters now is not what the stone says but that it says it three times and in three different languages: in Classical Greek, the language of the Greek rulers and the state administration, and then in two forms of ancient Egyptian: the everyday writing of the people (known as Demotic) and the priestly hieroglyphics which had for centuries baffled Europeans. It was the Rosetta Stone that changed all that; it dramatically opened up the entire world of ancient Egypt to scholarship.

By the time of the Rosetta Stone, hieroglyphs were no longer in general use. They were used and understood only by priests in temples. Five hundred years later, even this restricted knowledge of how to read and write them had disappeared.

The Rosetta Stone survived unread through 2,000 years of further foreign occupations. After the Greeks came Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Muslim Arabs and Ottoman Turks – all had stretches of rule in Egypt. At some point the stone was moved from the temple at Sais in the Nile Delta, where it was first erected, to the town of el-Rashid, now known as Rosetta, about forty miles away.

Then, in 1798, Napoleon arrived. The French invasion was of course primarily military (they wanted to cut the British route to India). But with the French army came scholars. Soldiers rebuilding fortifications in Rosetta dug up the stone – and accompanying experts knew immediately that they had found something of great significance.

The French seized the stone as a trophy of war, but it never made it back to Paris. With his fleet destroyed by Nelson at the Battle of the Nile, Napoleon himself returned to France, leaving the French army behind. In 1801 the French surrendered to the British and Egyptian generals. The terms of the Treaty of Alexandria included the handing over of antiquities, among them the Rosetta Stone.

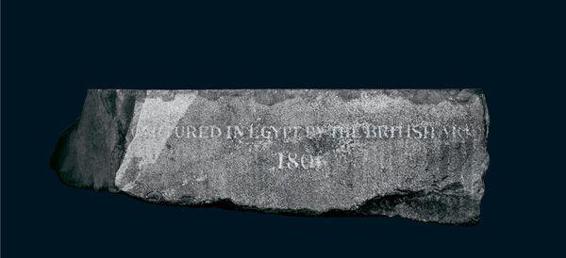

The inscription recording the stone’s capture from Napoleon’s troops

Most books will tell you, as I just have, that there are three languages on the Rosetta Stone, but if you look on the broken side you can see a fourth. There, painted in English, you can read:

CAPTURED IN EGYPT BY THE BRITISH ARMY IN

1801 (and elsewhere)

PRESENTED BY KING GEORGE III

. Nothing could make it clearer that while the text on the front of the stone is about the first European empire in Africa, Alexander the Great’s, the finding of the stone stands at the beginning of another European adventure: the bitter rivalry between Britain and France for dominance in the Middle East and in Africa, which continued from the time of Napoleon until the Second World War. I asked the Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif for her view of this history:

This stone makes me think of how often Egypt has been the theatre of other people’s battles. It’s one of the earliest objects through which you can trace Western colonial interest in Egypt. The French and the British argued over it; nobody seems to have considered that it belonged to neither of them. Egypt’s foreign rulers, from the Romans to the Turks to the British, have always made free with Egypt’s heritage. Egypt had foreign rulers for 2,000 years, and in 1952 much was made of the fact that Nasser was the first Egyptian ruler since the pharaohs

.

The Stone was brought back to the British Museum and immediately put on display – in the public domain, freely available for every scholar in the world to see – and copies and transcriptions were published worldwide. European scholars set about the task of understanding the mysterious hieroglyphic script. The Greek inscription was the one that every scholar could read and was therefore seen to be the key. But everybody was stuck. A brilliant English polymath, Thomas Young, correctly worked out that a group of hieroglyphs repeated several times on the Rosetta Stone represented the sounds of a royal name – that of Ptolemy. It was a crucial first step, but Young hadn’t quite cracked the code. A French scholar, Jean-François Champollion, then realized that not only the symbols for Ptolemy but all the hieroglyphs were both pictorial

and

phonetic – they recorded the

sound

of the Egyptian language. For example, on the last line of the hieroglyphic text on the stone, three signs spell out the sounds of the word for ‘stone slab’, in Egyptian

ahaj

, and then a fourth sign gives a picture showing the stone as it would originally have looked: a square slab with a rounded top. So sound and picture work together.

The last line of hieroglyphic text revealed that the glyphs were both pictorial and phonetic

By 1822, Champollion had finally worked the whole thing out. From then on the world could put words to the great objects – the statues and the monuments, the mummies and papyri – of ancient Egyptian civilization.

By the time of the Rosetta Stone, Egypt had already been under Greek rule for more than a hundred years, and the Ptolemies’ dynasty would rule for another 150. The dynasty ended infamously with the reign of Cleopatra VII – the Cleopatra who beguiled and seduced both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. But with the death of Antony and Cleopatra, Egypt was conquered by Augustus, and the Egypt of the Ptolemies became part of the Roman Empire.

Chinese Han Lacquer Cup

AD

4

Throughout history, as any anthropologist will tell you, the simplest way to bind people to you has been to give them a special gift – a present only you can give and only they are worthy to receive; a present like this object. I’ve been considering how the leaders of vast kingdoms and empires built and retained their supremacy, whether by borrowing the image of Alexander the Great, preaching the ideals of the Buddha in India or buying off the priesthood in Egypt. In Han Dynasty China 2,000 years ago the giving of imperial gifts was an activity central to the building of influence, and one which straddled the murky boundary between diplomacy and bribery.

Our cup comes from a turbulent period in the Han Dynasty. At the centre the emperor was under severe threat, while at the edges of the empire he was struggling to keep control. The Han, who had ruled since 202

BC

, extended Chinese power as far south as Vietnam, west to the steppes of central Asia and north to Korea, and in each of these places they had set up military colonies. As Han commerce and settlements grew in these outposts, so their governors gained in power, and there was always a risk that these might turn into independent fiefdoms. What the Chinese now call ‘splittism’ was a worry even then. The governors’ loyalty to the emperor needed to be secured. And one of the ways the emperor kept them onside was to give them gifts that carried huge imperial prestige. In the British Museum we have this exquisite lacquer wine cup which was probably given by the Han emperor to one of his military commanders in North Korea around the year 4.

It is very light and more like a small serving bowl than a wine cup – a bowl that would hold the equivalent of a very large glass of wine. The bowl is a shallow oval about 17 centimetres (7 inches) long, roughly the size and shape of a large mango. On each of the long sides there are gilded handles which give the cup its name – it’s known as an ear cup. The core of the cup is wood, and through some of the damage you can just see that wood; but most of it is covered in layer after layer of reddish-brown lacquer. The inside is plain, but the outside has been decorated with gold and bronze inlay – pairs of birds face each other, each sporting exaggerated claws against a background of geometric shapes and decorative spirals. The whole effect is of a costly, highly wrought object – elegant, stylish, confident. Everything about it speaks of assured taste and controlled opulence. Roel Sterckx, Professor of Chinese History at Cambridge University, knows exactly how much effort would go into making one of these drinking cups:

Lacquerware takes an enormous amount of time to make. It’s a very labour-intensive and a very tedious process, because the extraction of the sap of the lacquer tree is followed by all sorts of procedures, mixing with pigments, letting it cure, applying successive layers on to a wooden core to finally produce a beautiful piece. It would have involved several sets of artisans

.

High-quality lacquer was brilliantly smooth and virtually indestructible. Fine pieces like our cup required thirty or more separate coats, with long drying and hardening times between each one, so it would have taken about a month to make. Hardly surprising, then, that they were inordinately expensive; you could buy more than ten bronze cups for the price of one in lacquer. So lacquer cups were strictly reserved for top management – the imperial governors controlling the frontiers of the empire.