A History of the World in 100 Objects (37 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Our sculpture – one of the earliest known – probably dates from the third century

AD

, when Gandhara was ruled by the Kushan kings of northern India, whose empire stretched from Kabul to Islamabad. It was a wealthy region thanks to its position on the Silk Road, the trade routes linking China, India and the Mediterranean. From Gandhara the main route ran west through Iran to Alexandria in Egypt. Gandhara’s prosperity and political stability allowed the construction of a great landscape of Buddhist shrines, monuments and sculpture, as well as supporting further missionary expansion. The religions that survive today are the ones that were spread and sustained by trade and power. It’s profoundly paradoxical: Buddhism, the religion founded by an ascetic who spurned all comfort and riches, flourished thanks to the international trade in luxury goods. With those valuable commodities, like silk, went the monks and the missionaries, and with them went the Buddha, in human form, perhaps because such an image helps when you are teaching across a language barrier.

There are four standard poses for the Buddha that we know today: he can be shown lying, sitting, standing or walking. Each pose reflects a particular aspect of his life and activity, rather than a moment or an event. Our sculpture shows him in his enlightened state. He is robed as a monk, as might be expected, but unlike a monk his head is not shaved. He has dispensed with finery and removed his princely jewellery. His ears are no longer weighted down with gold – but the elongated lobes still have the empty holes that show that this man was once

a prince. His cross-legged lotus position is a pose used for meditation and, as here, for teaching.

But this statue, and the thousands made later that look so like it, has a purpose. Thupten Jinpa, a former monk and translator for the Dalai Lama, explains how you use an image like this one as a help on your journey towards enlightenment:

Religious practitioners internalize the image of the Buddha by first looking at the image and then bringing that image of the Buddha within themselves in a sort of mental image. And then they reflect upon the qualities of the Buddha – Buddha’s body, speech and mind. The image of the Buddha plays a role of recalling in the mind of the devotee, the historical teacher, the Buddha, his experience of awakening and the key events in his life. There are different forms of the Buddha that actually symbolize those events. For example, there is a very famous posture of the Buddha seated but with his hand in a gesture of preaching. Technically this hand gesture is referred to as the gesture of turning the wheel of

Dharma

:

Dharmachakra

.

This is the hand gesture of our seated Buddha. The

Dharmachakra

, or ‘Wheel of Law’, is a symbol that represents the path to enlightenment. It’s one of the oldest known Buddhist symbols found in Indian art. In the sculpture Buddha’s fingers stand in for the spokes of the wheel and he’s ‘setting in motion the Wheel of Law’ to his followers, who will eventually be able to renounce the material states of illusion, suffering and individuality for the immaterial state of ‘the highest happiness’ – Nirvana. The Buddha teaches that:

It is only the fool who is deceived by the outward show of beauty; for where is the beauty when the decorations of the person are taken away, the jewels removed, the gaudy dress laid aside, the flowers and chaplets withered and dead? The wise man, seeing the vanity of all such fictitious charms, regards them as a dream, a mirage, a fantasy.

All Buddhist art aims to detach the faithful from the physical world, even if it uses a physical image like our statue to do so. In the next chapter we have a religion that believes in the delights of material abundance, and it has a profusion of gods: it is Hinduism.

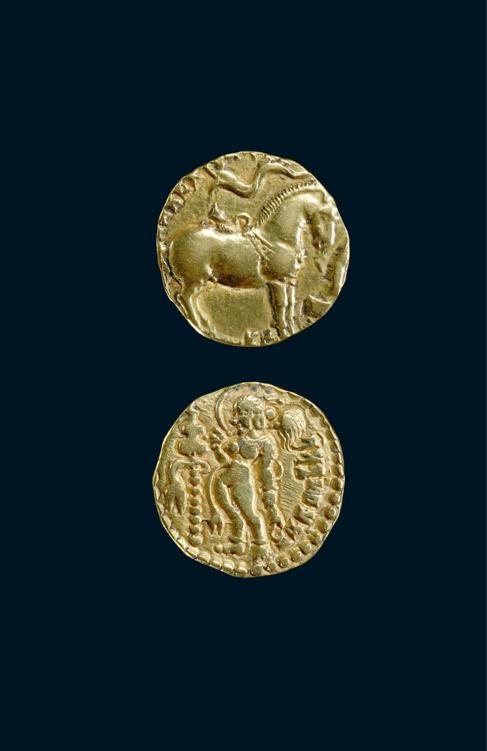

Gold Coins of Kumaragupta I

MINTED AD

415–450

In north-west London is what must be one of the most startling buildings in the capital, indeed in the whole of the UK. It’s the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, the Neasden Hindu temple – a huge white building, made of marble quarried in Italy, elaborately carved in India by more than 1,500 craftsmen and then shipped to England.

After taking their shoes off, visitors enter a large hall, sumptuously decorated with sculptures of the Hindu gods, carved in white Carrara marble. They cannot enter in the middle of the day – at that time the gods are asleep, and music is played every day, at around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, to wake them up. Images like these sculptures, of Shiva, Vishnu and the other Hindu gods, strike us now as timeless, but there was one particular moment when this way of seeing the gods began. The visual language of Hinduism, just like Buddhism and Christianity, crystallized somewhere around the year 400, and the forms of these deities now in Neasden can be traced back to India’s great Gupta Empire of around 1,600 years ago.

Gold coin showing a horse on one side and a goddess, probably Lakshmi, on the other

To interact with gods we need to be able to recognize them – but how are they to be identified? Hinduism is a religion that, although it has its ascetic aspect, acknowledges the delights of material abundance, and it has a profusion of gods, to be found in temples covered in decorations, flowers and garlands. The great gods Shiva and Vishnu are easily recognizable, Shiva with his wife Parvati and his trident, and Vishnu sitting with his four arms, holding discus and lotus flower. Often found nearby is a god who was particularly important for the Gupta kings of some 1,600 years ago, Shiva’s son Kumara (more familiar now as Karttikeya). All these Hindu gods began to assume the shapes we recognize today in the brand-new temples built by the Gupta kings of northern India around the year 400.

In the Coins and Medals Department of the Museum we have two coins of the Indian king Kumaragupta I, who ruled from

AD

414 to 455. They show very different aspects of this king’s religious life. They are each almost exactly the size of a 1p coin but are made of solid gold, so they sit quite heavily in the hand. On the first coin, where you would normally expect to see the king, there is a horse – a magnificent standing stallion. He is decorated with ribbons, and a great pennant flutters over his head. Around the coin, in Sanskrit, is an inscription that translates as ‘King Kumaragupta, the supreme lord, who has conquered his enemies’.

Why put a horse on the coin instead of the king? This design looks back to an ancient sacrificial ritual, established long before Hinduism, that had been observed by the Indian kings of the past and was preserved and continued by the Guptas. It was an awesome and elaborate year-long process that a king might do once in a lifetime – it cost a fortune and culminated in a massive theatrical act of sacrifice. Kumaragupta decided that he would perform this rite.

A stallion was selected and ritually purified, then released to roam for a year, followed and observed by an escort of princes, heralds and attendants. A key part of their job was to prevent it from mating: the stallion had to remain pure. At the end of its year of sexually frustrated freedom, the horse was retrieved in a complex set of ceremonies before being killed by the king himself, using a gold knife, in front of a large crowd of spectators. Our gold coin commemorates Kumaragupta’s performance of this ancient pre-Hindu ritual that reaffirmed his legitimacy and his supremacy. But, at the same time, Kumaragupta was vigorously promoting other, newer religious practices, invoking other gods in support of his earthly power. He was spending large sums of money on building temples and filling them with statues and paintings of the Hindu gods, making them manifest to their worshippers in a new and striking form. He and his contemporaries were, in effect, creating the gods anew.

The Gupta Dynasty began a little after the year 300 and rapidly expanded from its base in northern India until it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. By 450 the Gupta Empire was a regional superpower, ranking with Iran and the Eastern Roman Empire, Byzantium. Not long after Constantine had granted tolerance to Christianity in Rome in 313 the Gupta kings in northern India set down many of the enduring forms of Hinduism – creating the complex apparatus of the faith, with its temples and priests, and commissioning the images of the gods that we know now.

Why did this happen at this point in history? As with Christianity and Buddhism it seems to relate to empire, wealth, a faith that is gaining new devotees and the power of art. Only stable, rich and powerful states can commission great art and architecture that, unlike text or language, can be instantly understood by anyone – a great advantage in multilingual empires. And once buildings and sculptures exist, they last, and become the pattern for the future. But whereas in Rome Christianity was soon imposed as the exclusive religion of the Empire, for the Gupta kings worship of the Hindu gods was always only one of the ways in which the divine could be apprehended and embraced. This is a world which seems to be at ease with complexity, happy to live with many truths and, indeed, to proclaim them all as an official part of the state.

What sort of relationship between devotee and deity was being fostered during this flourishing of Hinduism under the Guptas? Shaunaka Rishi Das, the Hindu cleric and Director of the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, explains:

Hindus will see a deity, on the whole, as God present. God can manifest anywhere, so the physical manifestation of the image is considered to be a great aid in gaining the presence of God. By going to the temple, you see this image that is the presence. Or you can have the image in your own home – Hindus will invite God to come into this deity-form, they will wake god up in the morning with an offering of sweets. The deity will have been put to bed

in

a bed the night before, raised up, it will be bathed in warm water, ghee, honey, yoghurt, and then dressed in handmade dresses – usually made of silk – and garlanded with beautiful flowers and then set up for worship for the day. It’s a very interesting process of practising the presence of God.

The god whose presence Kumaragupta chose to celebrate most intensely is obvious from his name; he selected Kumara, god of war, and it is Kumara that we see on our second gold coin. Naked to the waist, he holds a spear and is mounted on a sacred peacock – not the vainglorious peacock of Western tradition, but an aggressive and terrifying bird that he is riding into war. This image, created 1,600 years ago, is still immediately recognizable today: you can see it in many shrines. But there’s one detail worth mentioning – Kumara and his peacock are shown standing on a plinth. We are looking at an image not of a god, but of a statue of the god as it would have been seen in a temple, just the sort of statue that Kumaragupta himself might have commissioned. It’s a tradition of temple imagery that emerges at this point and continues to the present day.

Gold coin showing a statue of the god Kumara riding a peacock on one side and King Kumaragupta himself on the other

On the other side of the coin is King Kumaragupta himself, also with a peacock, but unlike Kumara he doesn’t ride it. Instead, he elegantly offers grapes to his god’s sacred bird. Crowned and haloed, the king wears heavy earrings and an elaborate necklace, and the inscription tells us that this is ‘Kumaragupta, deservedly victorious with an abundance of virtues’.

The gold coin does what coins have always done uniquely well: they tell everyone who handles them that their ruler enjoys the special favour of heaven and, in this case, the special favour of heaven’s commander-in-chief, because he is linked in a particular way to the god Kumara. It’s a form of mass communication invented around the death of Alexander (see

Chapter 31

) that rulers have exploited ever since: the Grace of God claimed for the Queen on every British penny stands in the same tradition as Kumaragupta’s coin. But Kumaragupta’s image of his god is about much more than the theology of power – it speaks also of a universal human desire. It is evidence of the longing for a direct personal connection with the divine that everyone – not just the king – could access. Mediated by statues and images, it is a relationship that has been central to Hinduism every since.