A History of the World in 100 Objects (14 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

We need to know more about these great Indus cities, and our knowledge is still growing steadily, but of course the big breakthrough would come if we could read the signs on the seals. We just have to wait. In the meantime, the total disappearance of these great urban societies is an uncomfortable reminder of just how fragile our own city life – indeed our own civilization – is today.

Jade Axe

4000–2000

BC

For most of history, to live in Britain has been to live at the edge of the world. But that doesn’t mean that Britain was isolated.

We’ve explored how 5,000 years ago cities and states grew up along some of the great rivers of the world, in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Pakistan and India. Their styles of leadership and their architecture, their writing and the international trading networks, allowed them to acquire new skills and to exploit new materials. But in the world beyond these great river valleys, the story was different. From China to Britain, people continued to live in relatively small farming communities, with none of the problems or opportunities of the new large urban centres. What they did share with them was a taste for the expensive and the exotic. And, thanks to well-established trade routes, even in Britain, on the extreme outside edge of the Asian/European landmass, they had long been able to obtain what they wanted.

In Canterbury around 4000

BC

a supreme object of desire was this polished jade axe. At first sight it looks like thousands of other stone axes in the British Museum collection, but it’s thinner and wider than most of them. It still looks absolutely brand new – and it’s very sharp. It’s the shape of a teardrop, about 21 centimetres (8 inches) long and about 8 centimetres (3 inches) wide at the base. It’s cool to the touch and extraordinarily, pleasingly smooth.

Axes occupy a special place in the human story, as we first glimpsed at the beginning of this book. The farming revolution in the Near East took generations to spread from there across the breadth of mainland Europe, but eventually, about 6,000 years ago, settlers reached British and Irish shores in skin-covered boats, bringing with them crop seeds and domesticated animals. They found thick forests covering the land. It was stone axes that enabled them to clear the spaces they needed to sow their seeds and graze their beasts. With axes the settlers made for themselves a new wooden world: they felled timber and built fences and trackways, houses and boats. These were the people who would also construct monuments like the first Stonehenge. Stone axes were the revolutionary tool that enabled our ancestors to create in England a green and pleasant land.

Axes like this one normally have a haft – that is, they’re fitted into a long wooden handle and they’re used like a modern axe. But it’s quite clear that our axe has never been hafted – in fact, it shows no signs of wear and tear at all. If I run my finger carefully round the blade end, I can’t feel even the smallest chip. The long flat surfaces are remarkably smooth and still have a glossy, mirror-like sheen.

The conclusion is inescapable. Not only has our axe not been used – it was never intended to be used, but rather to be admired. Mark Edmonds, of York University, explains how this magnificent prestige object was made:

If you have the good fortune to handle one of these axes – the feel in the hand, the balance, the weight, the smoothness – you can tell they have been polished to an extraordinary degree. To give that polish it will have been ground for hour upon hour against stone, then polished with fine sand or silt and water, and then rubbed backwards and forwards in the hand, perhaps with grease and leaves. That’s days and days of work. It gives the edge a really sharp and resilient bite, but the polishing also emphasizes the shape, allows the control of form, and brings out that extraordinary green and black speckled quality to the stone – it makes it instantly recognizable, and visually very striking. Those things may be just as important for this particular axe as the cutting edge.

The most exciting thing about this axe head, however, is not how it has been made, but what it is made of. It doesn’t have the usual grey-brown tones that you find in British stones and flints, but is a beautiful striking green. This axe is made from jade.

Jade is, of course, foreign to British soil – we tend to think of it as an exotic material from the Far East or from Central America; both the Chinese and the Central American civilizations are known to have valued jade far more highly than gold. These sources are thousands of miles away from Britain, so archaeologists were baffled for many years by where the jade in Europe could have come from. But there are actually sources of jade in continental Europe and, only a few years ago, in 2003 – some 6,000 years after our axe head was made – the precise origin of the stone it was made from was discovered. This luxury object is in fact Italian.

Archaeologists Pierre and Anne-Marie Pétrequin spent twelve hard years surveying and exploring the mountain ranges of the Italian Alps and the northern Apennines. Finally they found the prehistoric jade quarries that our axe comes from. Pierre Pétrequin describes the adventure:

We had worked in Papua New Guinea, and studied how the stone for the axe heads there comes from high in the mountains. This gave us the idea of going up very high in the Alps to try and find the sources of European jade. In the 1970s, many geologists had said that the axe-makers would just have used blocks of jade that had been carried down the mountains by rivers and glaciers. But that’s not the case. By going much higher up, between 1,800 and 2,400 metres above sea level, we found the chipping floors and the actual source material – still with signs of its having been used.

In some cases, the raw material exists as very large isolated blocks in the landscape. It’s quite clear that these were exploited by setting fire against them, which would allow the craftsmen then to knock off large flakes and work them up. So the sign that’s left on the stone is a slightly hollow area – a scar as it were – with a large number of chips beneath it.

The geological signature of any piece of jade can be precisely identified and matched. The Pétrequins found not only that the British Museum axe could be linked to the Italian Alps, but that the readings of the geological signatures are so accurate that the very boulder which the axe came from could be identified. No less extraordinary, Pierre Pétrequin was able to track down a geological sibling for our axe – another jade beauty found in Dorset:

The Canterbury axe head was from the same block as one that was found in Dorset, and it’s clear that people must have gone back to that block at different times, it might be centuries apart, but because it’s distinctive compositionally, it’s now possible to say … yes, that was the same block … chips off the old block!

The boulder from which the British Museum axe was chipped 6,000 years ago still sits in a high landscape, sometimes above the clouds, with spectacular vistas stretching as far as the eye can see. The jade-seekers seem to have deliberately chosen this special spot – they could easily have taken jade that was lying loose at the base of the mountains, but they climbed up through the clouds, probably because there they could take the stone that came from a place midway between our world on Earth and the celestial realm of gods and ancestors. So this jade was treated with extreme care and reverence, as if it contained special powers.

Having quarried rough slabs of jade, the stone-workers and miners would then have had to labour to get the material back down to a place where it could be crafted. It was a long, arduous task, completed on foot and using boats. Yet big blocks of this desirable stone have been found roughly 200 kilometres (120 miles) away – an astonishing achievement – and some of the material had an even longer journey to make. Jade from the Italian Alps eventually spread throughout northern Europe – some even as far as Scandinavia.

We can only guess about the journey of our particular axe, but our guesses are informed ones. Jade is extremely hard and difficult to work, so much effort must have gone into shaping it. It’s likely that first of all it was roughly sculpted in northern Italy, and then carried hundreds of miles across Europe to north-west France. It was probably polished there, because it’s like several other axes found in southern Brittany, where there seems to have been a fashion for acquiring exotic treasures like this. The people of Brittany even carved impressions of the axes into the walls of their vast stone tombs. Mark Edmonds considers the implications:

Beyond the practical tasks that you can use one of these things for, axes had a further significance – a significance that came from where they were found, who you got them from, where and when they were made, the sort of stories that were attached to them. Sometimes they were tools to be used and carried and forgotten about in the process, at other times they would come into focus as important symbols to be held aloft, to be used as reminders in stories about the broader world, and sometimes to be handed on – in an exchange with a neighbour, with an ally, with somebody you’d fallen out with, and perhaps in exceptional circumstances, on someone’s death, the axe was something that had to be dealt with. It had to be broken up like the body, or buried like the body, and we do have hundreds – if not thousands – of axes in Britain that appear to have been given that kind of treatment: buried in graves, deposited in ritual ceremonial enclosures, and even thrown into rivers.

That our axe has no signs of wear and tear is surely a consequence of the fact that its owners chose not to use it. This axe was designed to make a mark not on the landscape but in society, and its function was to be aesthetically pleasing. Its survival in such good condition suggests that people 6,000 years ago found it just as beautiful as we do today. Our love of the expensive and the exotic has a very long pedigree.

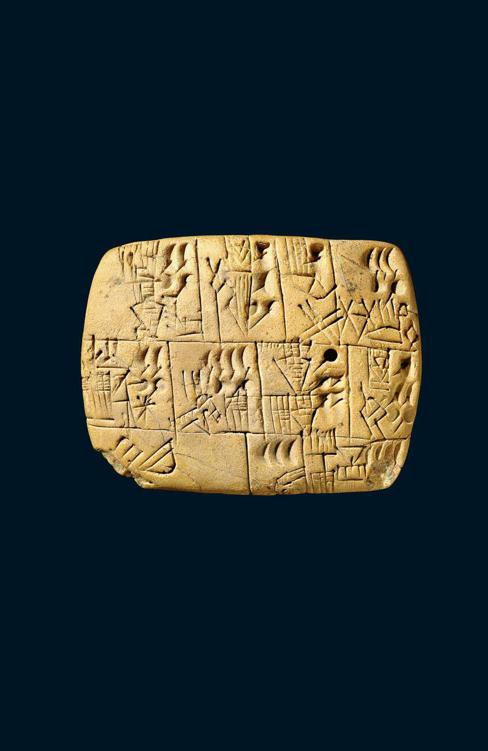

Early Writing Tablet

3100–3000

BC

Imagine a world without writing – without any writing at all. There would of course be no forms to fill in, no tax returns, but also no literature, no advanced science, no history. It is effectively beyond imagining, because modern life, and modern government, is based almost entirely on writing. Of all mankind’s great advances, the development of writing is surely the giant: it could be argued that it has had more impact on the evolution of human society than any other single invention. But when and where did it begin – and how? A piece of clay, made just over 5,000 years ago in a Mesopotamian city, is one of the earliest examples of writing that we know; the people who gave us the Standard of Ur have also left us one of the earliest examples of writing.

It is emphatically not great literature; it is about beer and the birth of bureaucracy. It comes from what is now southern Iraq, and it’s on a little clay tablet, about 9 centimetres by 7 (4 inches by 3) – almost exactly the same shape and size as the mouse that controls your computer.

Clay may not seem to us the ideal medium for writing, but the clay from the banks of the Euphrates and the Tigris proved to be invaluable for all kinds of purposes, from building cities to making pots, and even, as with our tablet, for giving a quick and easy surface on which to write. From the historian’s point of view, clay has one huge advantage: it lasts. Unlike the bamboo used by the Chinese to write on, which rots quickly, and unlike paper, which is so easily destroyed, sun-baked clay will survive in dry ground for thousands of years – and as a result we’re still learning from those clay tablets. In the British Museum we look after about 130,000 writing tablets from Mesopotamia, and scholars from all over the world come to study the collection.