Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (36 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

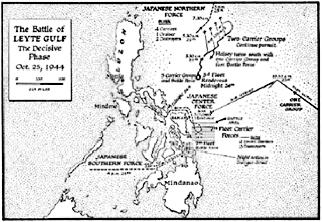

Halsey could not know how frail was their power, nor that most of the attacks he had endured came not from carriers at all but from airfields in Luzon itself. Kurita’s Centre Force was in retreat, Kinkaid could cope with the Southern Force and protect the landings at Leyte, the way was clear for a final blow, and Halsey ordered his whole fleet to steam

Triumph and Tragedy

223

northward and destroy Admiral Ozawa next day. Thus he fell into the trap. That same afternoon, October 24, Kurita again turned east and sailed once more for the San Bernardino Strait. This time there was nothing to stop him.

Meanwhile the Southern Japanese Force was nearing Surigao Strait, and that night they entered it in two groups.

A fierce battle followed, in which all types of vessel, from battleships to light coastal craft, were closely engaged.

1

The first group was annihilated by Kinkaid’s fleet, which was concentrated at the northern exit; the second tried to break through in the darkness and confusion, but was driven back. All seemed to be going well, but the Americans had still to reckon with Admiral Kurita. While Kinkaid was fighting in the Surigao Strait and Halsey was steaming in hard pursuit of the decoy force far to the north, Kurita had passed unchallenged in the darkness through the Strait of San Bernardino, and in the early morning of October 25 he fell upon a group of escort carriers who were supporting General MacArthur’s landings. Taken by surprise and too slow-moving to escape, the carriers could not at once rearm their planes to repel the onslaught from the sea. For about two and a half hours the small American ships fought a valiant retreat under cover of smoke. Two of their carriers, three destroyers, and over a hundred planes were lost, one of the carriers by suicide bomber attack; but they succeeded in sinking three enemy cruisers and damaging others

2

Help was far away. Kinkaid’s heavy ships were well south of Leyte, having routed the Southern Force, and were short of ammunition, and fuel. Halsey, with ten carriers and all his fast battleships, was yet more distant and although another of his carrier groups had been detached to refuel Triumph and Tragedy

224

and was now recalled it could not arrive for some hours.

Victory seemed to be in Kurita’s hands. There was nothing to stop him steaming into Leyte Gulf and destroying MacArthur’s amphibious fleet.

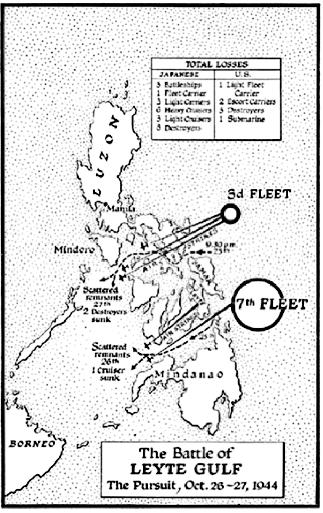

But once again Kurita turned back. His reasons are obscure. Many of his ships had been bombed and scattered by Kinkaid’s light escort carriers, and he now knew that the Southern Force had met with disaster. He had no information about the fortunes of the decoys in the north and was uncertain of the whereabouts of the American fleets. Intercepted signals made him think that Kinkaid and Halsey were converging on him in overwhelming strength and that MacArthur’s transports had already managed to escape. Alone and unsupported, he now abandoned the desperate venture for which so much had been sacrificed and which was about to gain its prize, and, without attempting to enter Leyte Gulf, he turned about and steered once more for the San Bernardino Strait. He hoped to fight a last battle on the way with Halsey’s fleet, but even this was denied him. In response to Kinkaid’s repeated calls for support Halsey had indeed at last turned back with his battleships, leaving two carrier groups to continue the pursuit to the north. During the day these destroyed all four of Ozawa’s carriers, but Halsey himself got back to San Bernardino too late. The Fleets did not meet. Kurita escaped. Next day Halsey’s and MacArthur’s planes pursued the Japanese admiral and sank another cruiser and two more destroyers. This was the end of the battle. It may well be that Kurita’s mind had become confused by the pressure of events. He had been under constant attack for three days, he had suffered heavy losses, and his flagship had been sunk soon after starting from Borneo. Those who have endured a similar ordeal may judge him.

Triumph and Tragedy

225

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was decisive. At a cost to themselves of three carriers, three destroyers, and a submarine the Americans had conquered the Japanese Fleet. The struggle had lasted from October 22 to October 27. Three battleships, four carriers, and twenty other enemy warships had been sunk, and the suicide bomber was henceforward the only effective naval weapon left to the foe. As an instrument of despair it was still deadly, but it carried no hope of victory.

This time there was no doubt about the result, and we hastened to send our congratulations.

Prime

Minister

to

27 Oct. 44

President Roosevelt

Triumph and Tragedy

226

Pray accept my most sincere congratulations, which

I tender on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, on the

brilliant and massive victory gained by the sea and air

forces of the United States over the Japanese in the

recent heavy battles.

We are very glad to know that one of His Majesty’s

Australian cruiser squadrons had the honour of sharing

in this memorable event.

Long should the victory be treasured in American history.

Apart from valour, skill, and daring it shed a light on the future more vivid and far reaching than any we had seen. It shows a battle fought less with guns than by predominance in the Air. I have told the tale fully because at the time it was almost unknown to the harassed European world.

Perhaps the most important single conclusion to be derived from study of these events is the vital need for unity of command in conjoint operations of this kind in place of the concept of control by co-operation such as existed between MacArthur and Halsey at this time. The Americans learnt this lesson and in the final operations planned against the homeland of Japan they intended that Supreme Command should be exercised by either Admiral Nimitz or General MacArthur as might be advisable at any given moment.

Triumph and Tragedy

227

Triumph and Tragedy

228

In the following weeks the fight for the Philippines spread and grew. By the end of November nearly a quarter of a million Americans had landed in Leyte, and by mid-December Japanese resistance was broken. MacArthur pressed on with his main advance, and soon landed without opposition on Mindoro Island, little more than a hundred miles from Manila itself. On January 9, 1945, a new phase opened with the landing of four divisions in Lingayen Gulf, north of Manila, which had been the scene of the major Japanese invasion three years before. Elaborate deception measures kept the enemy guessing where the blow would fall. It came as a surprise and was only lightly opposed. As the Americans thrust towards Manila resistance stiffened, but they made two more landings on the west coast and surrounded the city. A desperate defence held out until early March, when the last survivors were killed. Sixteen thousand Japanese dead were counted in the ruins.

Attacks by suicide aircraft were now inflicting considerable losses, sixteen ships being hit in a single day. The cruiser

Australia

was again unlucky, being hit five times in four days, but stayed in action. But this desperate expedient caused no check to the fleets. In mid-January Admiral Halsey’s carriers broke unmolested into the South China Sea, ranging widely along the coast and attacking airfields and shipping as far west as Saigon. At Hong Kong on January 16 widespread damage was inflicted, and great oil fires were started at Canton.

Although fighting in the islands continued for several months, command of the South China seas had already passed to the victor, and with it control of the oil and other supplies on which Japan depended.

Triumph and Tragedy

229

13

The Liberation of Western Europe

General Eisenhower Takes Command, September

1

— The Plight of the German Army — The

Allied

Thrusts

—

Montgomery’s

Counter-

Proposals — The Forward Leap — The Liberation

of Brussels, September

3

— Advance of the

Canadian Army — Surrender of Havre, September

12

— Capture of Dieppe, Boulogne, and

Calais — Ghent and Bruges Taken — The

American Pursuit — Fall of Charleroi, Mons,

Liége, and Luxembourg —“Overlord” and