Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (35 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Triumph and Tragedy

215

Earlier volumes have described the two-pronged American attack across the Pacific, and when this narrative opens in June 1944 it was well advanced. In the southwest General MacArthur had nearly completed his conquest of New Guinea, and in the centre Admiral Nimitz was pressing deep into the chain of fortified islands. Both were converging on the Philippines, and the struggle for this region was soon to bring about the destruction of the Japanese Fleet. The Fleet had already been much weakened and was very short of carriers, but Japan’s only hope of survival lay in victory at sea. To conserve her strength for this perilous but vital hazard her main fleet had withdrawn from Truk and was now divided between the East Indies and her home waters; but events soon brought it to battle. At the beginning of June Admiral Spruance Triumph and Tragedy

216

struck with his carriers at the Marianas, and on the 15th he landed on the fortified island of Saipan. If he captured Saipan and the adjacent islands of Tinian and Guam the enemy’s defence perimeter would be broken. The threat was formidable, and the Japanese Fleet resolved to intervene. That day five of their battleships and nine carriers were sighted near the Philippines, heading east. Spruance had ample time to make his dispositions. His main purpose was to protect the landing at Saipan. This he did. He then gathered his ships, fifteen of which were carriers, and waited for the enemy to the west of the island. On June 19

Japanese carrier-borne aircraft attacked the American carrier fleet from all directions, and air-fighting continued throughout the day. The Americans suffered little damage, and so shattered the Japanese air squadrons that their carriers had to withdraw.

That night Spruance searched in vain for the vanished enemy. Late in the afternoon of the 20th he found them about 250 miles away. Attacking just before sunset, the American airmen sank one carrier and damaged four others, besides a battleship and a heavy cruiser. The previous day American submarines had sunk two other large carriers. No further attack was possible, and remnants of the enemy fleet managed to escape, but its departure sealed the fate of Saipan. Though the garrison fought hard the landings continued, the build-up progressed, and by July 9 all organised resistance came to an end. The neighbouring islands of Guam and Tinian were overcome, and by the first days of August the American grip on the Marianas was complete.

The tall of Saipan was a great shock to the Japanese High Command, and led indirectly to the dismissal of General Tojo’s Government. The enemy’s concern was well founded. The fortress was little more than 1,300 miles from Triumph and Tragedy

217

Tokyo. They had believed it was impregnable; now it was gone. Their southern defence regions were cut off and the American heavy bombers had gained a first-class base for attacking the very homeland of Japan. For a long time United States submarines had been sinking Japanese merchantmen along the China coast, and now the way was open for other warships to join in the onslaught. Japan’s oil and raw materials would be cut off if the Americans advanced any farther. The Japanese Fleet was still powerful, but unbalanced, and so weak in destroyers, carriers, and air-crews that it could no longer fight effectively without land-based planes. Fuel was scarce, and not only hampered training, but made it impossible to keep the ships concentrated in one place, so that in the late summer most of the heavy vessels and cruisers lay near Singapore and the oil supplies of the Dutch East Indies, while the few surviving carriers remained in home waters, where their new air groups were completing their training.

The plight of the Japanese Army was little better. Though still strong in numbers, it sprawled over China and Southeast Asia or languished in remote islands beyond reach of support. The more sober-minded of the enemy leaders began to look for some way of ending the war; but their military machine was too strong for them. The High Command brought reinforcements from Manchuria and ordered a fight to the finish both in Formosa and the Philippines. Here and in the homeland the troops would die where they stood. The Japanese Admiralty were no less resolute. If they lost the impending battle for the islands the oil from the East Indies would be cut off. There was no purpose, they argued, in preserving ships without fuel.

Steeled for sacrifice but hopeful of victory, they decided in August to send the entire Fleet into battle.

Triumph and Tragedy

218

On September 15 the Americans made another advance.

General MacArthur seized Morotai Island, midway between the western tip of New Guinea and the Philippines, and Admiral Halsey, who had now assumed command of the United States naval forces, captured an advanced base for his fleet in the Palau group. These simultaneous moves were of high importance. At the same time Halsey continually probed the enemies’ defences with his whole force. Thus he hoped to provoke a general action at sea which would enable him to destroy the Japanese Fleet, particularly its surviving carriers. The next leap would be at the Philippines themselves, and there now occurred a dramatic change in the American plan. Till then our Allies had purposed to invade the southernmost portion of the Philippines, the island of Mindanao, and planes from Halsey’s carriers had already attacked the Japanese airfields both there and in the large northern island of Luzon. They destroyed large numbers of enemy aircraft, and discovered in the clash of combat that the Japanese garrison at Leyte was unexpectedly weak. This small but now famous island, lying between the two larger but strategically less important land masses of Mindanao and Luzon became the obvious point for the American descent.

On September 13, while the Allies were still in conference at Quebec, Admiral Nimitz, at Halsey’s suggestion, urged its immediate invasion. MacArthur agreed, and within two days the American Chiefs of Staff resolved to attack on October 20, two months earlier than had been planned. Such was the genesis of the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

The Americans opened the campaign on October 10 with raids on airfields between Japan and the Philippines.

Devastating and repeated attacks on Formosa provoked

Triumph and Tragedy

219

the most violent resistance, and from the 12th to the 16th there followed a heavy and sustained air battle between ship-borne and land-based aircraft. The Americans inflicted grievous losses both in the air and on the ground, but suffered little themselves, and their carrier fleet withstood powerful land-based air attack. The result was decisive.

The enemy’s Air Force was broken before the battle for Leyte was joined. Many Japanese naval aircraft destined for the fleet carriers were improvidently sent to Formosa as reinforcements and there destroyed. Thus in the supreme naval battle which now impended the Japanese carriers were manned by little more than a hundred partially trained pilots.

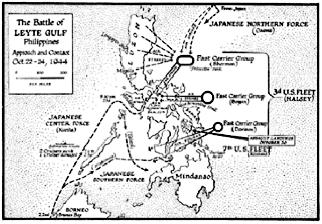

To comprehend the engagements which followed a study of the accompanying maps is necessary. The two large islands of the Philippines, Luzon in the north and Mindanao in the south, are separated by a group of smaller islands, of which Leyte is the key and centre. This central group is pierced by two navigable straits, both destined to dominate this famous battle. The northerly strait is San Bernardino, and about 200 miles south of it, leading directly to Leyte, is the strait of Surigao. The Americans, as we have seen, intended to seize Leyte, and the Japanese were resolved to stop them and to destroy their fleet. The plan was simple and desperate. Four divisions under General MacArthur would land on Leyte, protected by the guns and planes of the American Fleet — so much they knew or guessed.

Draw off this fleet, entice it far to the north, and engage it in a secondary battle — such was the first step. But this would be only a preliminary. As soon as the main Fleet was lured away two strong columns of warships would sail through the straits, one through San Bernardino and the other Triumph and Tragedy

220

through Surigao, and converge on the landings. All eyes would be on the shores of Leyte, all guns trained on the beaches, and the heavy ships and the big aircraft-carriers which alone could withstand the assault would be chasing the decoy force in the far north. The plan very nearly succeeded.

On October 17 the Japanese Commander-in-Chief ordered his fleet to set sail. The decoy force, under Admiral Ozawa, the Supreme Commander, sailing direct from Japan, steered for Luzon. It was a composite force, including carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. Ozawa’s task was to appear on the eastern coast of Luzon, engage the American fleet, and draw it away from the landings in Leyte Gulf. The carriers were short of both planes and pilots, but no matter. They were only bait, and bait is made to be eaten. Meanwhile the main Japanese striking forces made for the straits. The larger, or what may be termed the Centre Force, coming from Singapore, and consisting of five battleships, twelve cruisers, and fifteen destroyers, under Admiral Kurita, headed for San Bernardino to curl round Samar island to Leyte; the small, or Southern Force, in two independent groups, comprising in all two battleships, four cruisers, and eight destroyers, sailed through Surigao.

On October 20 the Americans landed on Leyte. At first all went well. Resistance on shore was weak, a bridgehead was quickly formed, and General MacArthur’s troops began their advance. They were supported by Admiral Kinkaid’s Seventh United States Fleet, which was under MacArthur’s command, and whose older battleships and small aircraft-carriers were well suited to amphibious operations. Farther away to the northward lay Admiral Halsey’s main fleet, shielding them from attack by sea.

Triumph and Tragedy

221

I was on my way home from Moscow at the time, but Field Marshal Brooke and I recognised the importance of what had happened and we sent the following telegram:

Prime Minister and C.

22 Oct. 44

I.G.S.

to

General

MacArthur

Hearty congratulations on your brilliant stroke in the

Philippines.

All good wishes.

The crisis however was still to come. On October 23

American submarines sighted the Japanese Centre Force (Admiral Kurita) off the coast of Borneo and sank two of its heavy cruisers, one of which was Kurita’s flagship, and damaged a third. Next day, October 24, planes from Admiral Halsey’s carriers joined in the attack. The giant battleship

Musashi,

mounting 9 sixteen-inch guns, was sunk, other vessels were damaged, and Kurita turned back.

Triumph and Tragedy

222

The American airmen brought back optimistic and perhaps misleading reports, and Halsey concluded, not without reason, that the battle was won, or at any rate this part of it.

He knew that the second or Southern enemy force was approaching the Surigao Strait, but he judged, and rightly, that it could be repelled by Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet.

But one thing disturbed him. During the day he had been attacked by Japanese naval planes. Many of them were shot down, but the carrier

Princeton

was damaged and had later to be abandoned. The planes, he reasoned, probably came from carriers. It was most unlikely that the enemy had sailed without them, yet none had been found. The main Japanese Fleet, under Kurita, had been located, and was apparently in retreat, but Kurita had no carriers, neither were there any in the Southern Force. Surely there must be a carrier force, and it was imperative to find it. He accordingly ordered a search to the north, and late in the afternoon of October 24 his flyers came upon Admiral Ozawa’s decoy force, far to the northeast of Luzon and steering south. Four carriers, two battleships equipped with flying decks, three cruisers, and ten destroyers! Here, he concluded, was the source of the trouble and the real target. If he could now destroy these carriers, he and his Chief of Staff, Admiral Carney, rightly considered that the power of the Japanese Fleet to intervene in future operations would be broken irretrievably. This was a dominating factor in his mind and would be of particular advantage when MacArthur came later to attack Luzon.