Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (38 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

2. On the other side there are factors to be noted.

Apart from Cherbourg and Arromanches, we have not

yet obtained any large harbours. The Germans intend

to defend the mouth of the Scheldt, and are still

resisting in the northern suburbs of Antwerp. Brest has

not been taken in spite of very heavy fighting, and at

least six weeks will be needed after it is taken before it

is available. Lorient still holds out. No attempt has been

made to take and clear the port of St. Nazaire, which is

about twice as good as Brest and twice as easy to take.

No attempt has been made to get hold of Bordeaux.

Unless the situation changes remarkably the Allies will

still be short of port accommodation when the

equinoctial gales are due.

3. One can already foresee the probability of a lull in

the magnificent advances we have made. General

Patton’s army is heavily engaged on the line Metz-Nancy. Field-Marshal Montgomery has explained his

misgivings as to General Eisenhower’s future plan. It is

difficult to see how the Twenty-first Army Group can

advance in force to the German frontier until it has

cleared up the stubborn resistance at the Channel ports

and dealt with the Germans at Walcheren and to the

north of Antwerp….

6. No one can tell what the future may bring forth.

Will the Allies be able to advance in strength through

the Siegfried Line into Germany during September, or

will their forces be so limited by supply conditions and

the lack of ports as to enable the Germans to

consolidate on the Siegfried Line? Will the Germans

withdraw from Italy? — in which case they will greatly

strengthen their internal position. Will they be able to

draw on their forces, at one time estimated at between

twenty-five and thirty-five divisions, in the Baltic States?

The fortifying and consolidating effect of a stand on the

frontier of the native soil should not be underrated. It is

Triumph and Tragedy

237

at least as likely that Hitler will be fighting on January 1

as that he will collapse before then.

2

If he does collapse

before then, the reasons will be political rather than

purely military.

My view was unhappily to be justified.

But there was still the chance of crossing the lower Rhine.

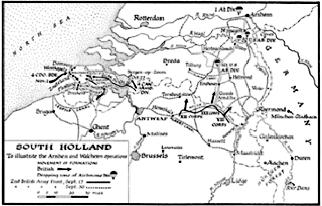

Eisenhower thought this prize so valuable that he gave it priority over clearing the shores of the Scheldt estuary and opening the port of Antwerp. To renew Montgomery’s effort Eisenhower gave him additional American transport and air supply. The First Airborne Army, under the American General Brereton, composed of the 1st and 6th British Airborne Divisions, three U.S. divisions, and a Polish brigade, with a great complement of British and American aircraft, stood ready to strike from England. Montgomery resolved to seize a bridgehead at Arnhem by the combined action of airborne troops and the XXXth Corps, who were fighting in a bridgehead across the Meuse-Scheldt canal on the Dutch border.

3

He planned to drop the 1st British Airborne Division, supported later by the Polish brigade, on the north bank of the lower Rhine to seize the Arnhem bridge. The 82d U.S. Division was to capture the bridges at Nijmegen and Grave, while the 101st U.S. Division secured the road from Grave to Eindhoven. The XXXth Corps, led by the Guards Armoured Division, would force their way up the road to Eindhoven and thence to Arnhem along the

“carpet” of airborne troops, hoping to find the bridges over the three major water obstacles already safely in their hands.

Triumph and Tragedy

238

The preparations for this daring stroke, by far the greatest operation of its kind ever attempted, were complicated and urgent, because the enemy were growing stronger every day. It is remarkable that they were completed by the set date, September 17. There were not sufficient aircraft to carry the whole airborne force simultaneously, and the movement had to be spread over three days. However, on the 17th the leading elements of the three divisions were well and truly taken to their destinations by the fine work of the Allied air forces. The 101st U.S. Division accomplished most of their task, but a canal bridge on the road to Eindhoven was blown and they did not capture the town till the 18th. The 82d U.S. Division also did well, but could not seize the main bridge at Nijmegen.

From Arnhem the news was scarce, but it seemed that some of our Parachute Regiment had established themselves at the north end of the bridge. The Guards Armoured Division of the XXXth Corps began to advance in the afternoon up the Eindhoven road, preceded by an artillery barrage and rocket-firing planes. The VIIIth Corps on the right and the XIIth on the left protected the flanks of the XXXth. The road was obstinately defended, and the Guards did not reach the Americans till the afternoon of the 18th. German attacks against the narrow Eindhoven-Nijmegen salient began next day and grew in strength. The 101st Division had great difficulty in keeping the road open.

At times traffic had to be stopped until the enemy were beaten off. By now the news from Arnhem was bad. Our parachutists still held the northern end of the bridge, but the enemy remained in the town, and the rest of the 1st Airborne Division, which had landed to the west, failed to break in and reinforce them.

Triumph and Tragedy

239

The canal was bridged on the 18th, and early next morning, the Guards had a clear run to Grave, where they found the 82d U.S. Division. By nightfall they were close to the strongly defended Nijmegen bridge, and on the 20th there was a tremendous struggle for it. The Americans crossed the river west of the town, swung right, and seized the far end of the railway bridge. The Guards charged across the road bridge. The defenders were overwhelmed and both bridges were taken intact.

There remained the last lap to Arnhem, where bad weather had hampered the fly-in of reinforcements, food, and ammunition, and the 1st Airborne were in desperate straits.

Unable to reach their bridge, the rest of the division was confined to a small perimeter on the northern bank and endured violent assaults. Every possible effort was made from the southern bank to rescue them, but the enemy were too strong. The Guards, the 43d Division, the Polish Parachute Brigade, dropped near the road, all failed in their gallant attempts at rescue. For four more days the struggle went on, in vain. On the 25th Montgomery ordered the survivors of the gallant 1st Airborne back. They had to cross the fast-flowing river at night in small craft and under close-range fire. By daybreak about 2400 men out of the original 10,000 were safely on our bank.

Even after all was over at Arnhem there was hard fighting for a fortnight to hold our gains. The Germans conceived that our salient imperilled the whole western bank of the lower Rhine, and later events proved they were right. They made many heavy counter-attacks to regain Nijmegen. The bridge was bombed from the air, and damaged, though not destroyed, by swimmers with demolition charges. Gradually the three corps of the Second Army expanded the fifty-mile

Triumph and Tragedy

240

salient until it was twenty miles wide. It was still too narrow, but for the moment it sufficed.

Heavy risks were taken in the Battle of Arnhem, but they were justified by the great prize so nearly in our grasp. Had we been more fortunate in the weather, which turned against us at critical moments and restricted our mastery in the air, it is probable that we should have succeeded. No risks daunted the brave men, including the Dutch Resistance, who fought for Arnhem.

It was not till I returned from Canada, where the glorious reports had flowed in, that I was able to understand all that had happened. General Smuts was grieved at what seemed to be a failure, and I telegraphed:

Prime Minister to Field-9 Oct. 44

Marshal Smuts

Triumph and Tragedy

241

I like the situation on the Western Front, especially

as enormous American reinforcements are pouring in

and we hope to take Antwerp before long. As regards

Arnhem, I think you have got the position a little out of

focus. The battle was a decided victory, but the leading

division, asking, quite rightly, for more, was given a

chop. I have not been afflicted by any feeling of

disappointment over this and am glad our commanders

are capable of running this kind of risk.

Clearing the Scheldt estuary and opening the port of Antwerp had been delayed for the sake of the Arnhem thrust. Thereafter it was given first priority. During the last fortnight of September a number of preliminary actions had set the stage. The IId Canadian Corps had forced the enemy back from the line Antwerp-Ghent-Bruges into the restricted Breskens “island,” bounded on the south by the Leopold Canal. East of Antwerp the 1st Corps, also under the Canadian Army command, had reached and crossed the Antwerp-Turnhout canal.

The problem was threefold: the capture of the Breskens

“island”; the occupation of the peninsula of South Beveland; finally, the capture of Walcheren Island by attacks from east, south, and west. The first two proceeded simultaneously. Breskens “island,” defended by an experienced German division, proved tough, and there was hard fighting to cross the Leopold Canal. The scales were turned by a Canadian brigade, which embarked upstream, landed at the eastern extremity of the “island,” and forced a way along the shore towards Breskens, which fell on October 22. Meanwhile the Ist Corps had steadily advanced northwest from the Antwerp-Turnhout canal, meeting increased opposition as they went. The South Beveland