Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (34 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

to

2 Dec. 44

General Hollis, for C.

O.S. Committee

Triumph and Tragedy

209

There can be no dispute about the right of the

Generalissimo to withdraw any division he requires to

defend himself against the Japanese attack upon his

vitals. I have little doubt he will first wish to bring home

the two divisions [trained by the Americans]. We cannot

make a fight about this. If he claims them he must have

them. What happens [afterwards] in Burma demands

urgent but subsequent study. Pray let me have a

telegram drafted agreeing with the Americans about the

withdrawal of the divisions.

The loss of two good Chinese divisions was not so grave an inconvenience to the Burma operations as that of the transport squadrons. The Army was four hundred miles beyond its railhead and General Slim relied on air supply to help the tenuous road link. Mountbatten’s general plans depended on his transport aircraft. The squadrons needed for China had to go, and although they were later replaced, mostly from British sources, their absence at a critical time caused severe delay to the campaign.

In spite of all this the Fourteenth Army broke out of the hills into the plain northwest of Mandalay. While the leading division of General Messervey’s IVth Corps drove south in secret to establish a bridgehead over the Irrawaddy south of its junction with the Chindwin, General Stopford’s XXXIIId Corps, supported by the 221 Group R.A.F., occupied the north bank of the Irrawaddy upstream from that junction.

The 19th Indian Division was already across the river in two places forty miles north of Mandalay. By the end of January General Sultan’s forces had reached Namkhan, on the old Burma-China road, and made contact with the Yunnan force farther east. The land route to China, closed by the Japanese invasion of Burma in the spring of 1942, was open again. The first road convoy from Assam reached the Chinese frontier on January 28.

Triumph and Tragedy

210

Prime Minister to

23 Jan. 45

Admiral Mountbatten

(Southeast Asia)

On behalf of His Majesty’s Government I send you

our warmest congratulations on having reopened the

land route to China in fulfillment of the first part of the

directive given to you at Quebec. It reflects the greatest

credit on yourself, all your field commanders, and,

above all, upon the well-tried troops of the Fourteenth

Army that this should have been achieved despite your

many disappointments in the delay of promised

reinforcements.

His Majesty’s Government warmly and gratefully

recognise, as you have done throughout, the ready

assistance given in all possible ways by the forces of

the United States and also by those of China.

Later developments in Central Burma fall to another chapter, but the winter fighting in the Arakan, subsidiary but important, must be recorded here. Its importance lay in two spheres. The air-lift to the Fourteenth Army in the Mandalay plain had nearly reached the limit of the Dakota aircraft.

Moreover, all the stores thus carried forward had to be brought to the dispatching airfields by the hard-worked Assam railway. If General Christison’s XVth Corps could establish airfields south of Akyab, aircraft operating from there, and replenished by sea direct from India, could supply the Fourteenth Army in a southern thrust from Mandalay to Rangoon. Secondly, if the single Japanese division facing our superior forces in the Arakan was quickly defeated and dispersed, two or three of our divisions and their supporting 224 Group R.A.F., under Air Commodore the Earl of Bandon, could be taken for operations elsewhere.

Triumph and Tragedy

211

The Arakan offensive opened on December 12, and made good headway. By the end of the month our troops had reached the inlet which separates Akyab Island from the mainland and were preparing to assault. On January 2 an officer in an artillery observation aircraft saw no sign of the enemy. He landed on Akyab airfield, and was told by inhabitants that the Japanese had left. Most of the garrison had been drawn into the fighting farther north; the remaining battalion had been withdrawn two days before.

This was a strange anticlimax to the long story of Akyab, which for nearly three years had caused us much tribulation and many disappointments. Soon afterwards the XVth Corps occupied Ramree Island, developing air-strips there, and on the mainland occupied Kangaw after a sharp fight.

At the end of January the XVth Corps, like those farther north, had reached its primary objectives, and was ready for further advances.

Triumph and Tragedy

212

12

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

Ocean War against Japan

—

Creation of the British

Pacific Fleet — The Growing Maritime Strength of

the United States — American Tactics and

Japanese Defences

—

The Landing at Saipan,

June

15

— Admiral Spruance Gains a Decisive

Victory, June

20

— Conquest of the Marianas —

Dismay in Tokyo — The Advance to the Philippines — Air Battles over Formosa — The

Americans Land at Leyte Gulf, October

20

— The

Japanese Commander-in-Chief Resolves to

Intervene

—

Admiral Halsey and the Enemy Trap

—

Night Action in the Surigao Strait — The American

Landings in Peril — Arrival of the Suicide Bomber

—

Admiral Kurita Turns Back —Twenty-Seven

Japanese Warships Destroyed

—

The Landing in

Lingayen Gulf, January

9

,

1945

— The Fall of

Manila

—

The United States Gain Command of the

South China Seas.

O

CEAN WAR against Japan now reached its climax. From the Bay of Bengal to the Central Pacific Allied maritime power was in the ascendant. By April 1944 three British capital ships, two carriers, and some light forces were assembled in Ceylon. These were augmented by the American carrier

Saratoga

, the French battleship

Richelieu

, and a Dutch contingent. A strong flotilla of British submarines also arrived in February, and at once began to

Triumph and Tragedy

213

take toll of enemy shipping in the Malacca Strait. As the year advanced two more British carriers arrived, and the

Saratoga

returned to the Pacific. With these forces Admiral Somerville could do much more. In April his carriers struck at Sabang, at the northern end of Sumatra, and in May at the oil refinery and engineering works at Sourabaya, in Java. This operation lasted twenty-two days, and the fleet steamed seven thousand miles. In the following months the Japanese sea route to Rangoon was severed by British submarines and aircraft.

In August Admiral Somerville, who had commanded the Eastern Fleet through all the troubled times since March 1942, was relieved by Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, and soon afterwards succeeded Admiral Noble at the head of our Naval Delegation at Washington. A month later the progress of the war in Europe enabled us to reduce the Home Fleet to no more than a single battleship, with supporting forces. The move to the Far East was hastened, and two modern battleships, the

Howe

and

King George V,

joined Admiral Fraser. On November 22, 1944, the British Pacific Fleet came officially into existence, and subsequently took part in a series of operations account of which falls to a later chapter.

In the Pacific the organisation and production of the United States were in full stride, and had attained astonishing proportions. A single example may suffice to illustrate the size and success of the American effort. In the autumn of 1942, at the peak of the struggle for Guadalcanal, only three American aircraft-carriers were afloat; a year later there were fifty; by the end of the war there were more than a hundred. This achievement had been matched by an Triumph and Tragedy

214

increase in aircraft production which was no less remarkable. The advance of these great forces was animated by an aggressive strategy and an elaborate, novel, and effective tactic. The task which confronted them was formidable.

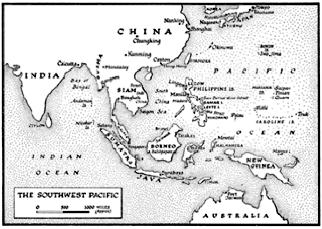

A chain of island-groups, nearly two thousand miles long, stretches southward across the Pacific from Japan to the Marianas and the Carolines. Many of these islands had been fortified by the enemy and equipped with good airfields, and at the southernmost end of the chain was the Japanese naval base of Truk. Behind this shield of archipelagos lay Formosa, the Philippines, and China, and in its shelter ran the supply routes for the more advanced enemy positions. It was thus impossible to invade or bomb Japan itself. The chain must be broken first. It would take too long to conquer and subdue every fortified island, and the Americans had accordingly advanced “leap-frog”

fashion. They seized only the more important islands and by-passed the rest; but their maritime strength was now so great and was growing so fast that they were able to establish their own lines of communication and break the enemy’s, leaving the defenders of the by-passed islands immobile and powerless. Their method of assault was equally successful. First came softening attacks by planes from the aircraft-carriers, then heavy and sometimes prolonged bombardment from the sea, and finally amphibious landing and the struggle ashore. When an island had been won and garrisoned land-based planes moved in and beat off counterattacks. At the same time they helped in the next onward surge. The fleets worked in echelons. While one group waged battle another prepared for a new leap. This needed very large resources, not only for the fighting, but also for developing bases along the line of advance. The Americans took it all in their stride.