Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (100 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

and drove on towards Hamburg. The XXXth Corps also had some hard fighting on their way to Bremen. The whole British advance was delayed by having to replace several hundreds of the bridges across the many waterways, which had been demolished by the enemy. Bremen fell on April 26. The VIIIth Corps, with the XIIth on their left and the XVIIIth U.S. Airborne Corps guarding their right flank, crossed the Elbe on April 29. They headed for the Baltic, so as to place themselves across the land-gate of Denmark.

On May 2 the 11th Armoured Division reached Lübeck, and Denmark was liberated by our troops amidst scenes of great rejoicing. Our 6th Airborne Division met the Russians at Wismar. Next day the XIIth Corps entered Hamburg.

Everywhere north of the Elbe the country was filled with masses of refugees and disorganised soldiery, fleeing from the Russians to surrender to the Western Allies. The end was near.

Triumph and Tragedy

616

12

Alexander’s Victory in Italy

Our Offensive is Postponed to the Spring — Allied

Air Attack — Hitler Forbids a Withdrawal — The

Weakness of the German Position — The Fall of

Bologna, April

21 —

The Allied Pursuit across the

Po — Naval Affairs — A New German Peace

Offer — Unconditional Surrender in Italy, April

29

—

Mussolini is Murdered — I Send my Victory

Congratulations to all Concerned — The End of a

Fine Campaign.

G

LEAMING SUCCESSES marked the end of our campaigns in the Mediterranean. In December Alexander had succeeded Wilson as Supreme Commander, while Mark Clark took command of the Fifteenth Army Group. After their strenuous efforts of the autumn our armies in Italy needed a pause to reorganise and restore their offensive power.

The long, obstinate, and unexpected German resistance on all fronts had made us and the Americans very short of artillery ammunition, and our hard experiences of winter campaigning in Italy forced us to postpone a general offensive till the spring. But the Allied Air Forces, under General Eaker, and later under General Cannon, used their thirty-to-one superiority in merciless attacks on the supply lines which nourished the German armies. The most important one, from Verona to the Brenner Pass, where Triumph and Tragedy

617

Hitler and Mussolini used to meet in their happier days, was blocked in many places for nearly the whole of March; other passes were often closed for weeks at a time, and two divisions being transferred to the Russian front were delayed almost a month.

The enemy had enough ammunition and supplies, but lacked fuel. Units were generally up to strength, and their spirit was high in spite of Hitler’s reverses on the Rhine and the Oder In Northern Italy they had twenty-seven divisions, four of them Italian, against our equivalent of twenty-three drawn from the British Empire, the United States, Poland, Brazil, and Italy.

1

The German High Command might have had little to fear had it not been for the dominance of our Air Forces, the fact that we had the initiative and could strike where we pleased, and their own ill-chosen defensive position, with the broad Po at their backs. They would have done better to yield Northern Italy and withdraw to the strong defences of the Adige, where they could have held us with much smaller forces and sent troops to help their overmatched armies elsewhere, or have made a firm southern face for the National Redoubt in the Tyrol mountains, which Hitler may have had in mind as his “last ditch.”

But defeat south of the Po spelt disaster. This must have been obvious to Kesselring, and was doubtless one of the reasons for the negotiations recorded in a previous chapter.

2

Hitler was of course the stumbling-block, and when Vietinghoff, who succeeded Kesselring, proposed a tactical withdrawal he was thus rebuffed: “The Fuehrer expects, now as before, the utmost steadiness in the fulfilment of your present mission to defend every inch of the North Italian areas entrusted to your command.”

Triumph and Tragedy

618

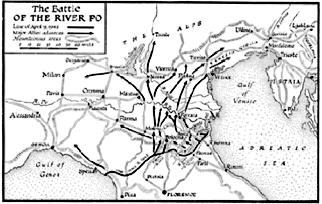

This eased our problem. If we could break through the Adriatic flank and reach the Po quickly all the German armies would be cut off and forced to surrender, and it was to this that Alexander and Clark bent their efforts when the stage was set for the final battle. The capture of Bologna, which had figured so much in our autumn plans, was no longer a principal object. The plan was for the Eighth Army, under General McCreery, to force a way down the road from Bastia

3

to Argenta, a narrow, strongly defended passage, flooded on both sides, but leading to more open ground beyond. When this was well under way General Truscott’s Fifth Army was to strike from the mountainous central front, pass west of Bologna, join hands with the Eighth Army on the Po, and together pursue to the Adige.

The Allied naval forces would make the enemy believe that amphibious landings were imminent on both east and west coasts.

Triumph and Tragedy

619

In the evening of April 9, after a day of massed air attacks and artillery bombardment, the Eighth Army attacked across the river Senio, led by the Vth and the Polish Corps.

On the 11th they reached the next river, the Santerno. The foremost brigade of the 56th Division and Commandos made a surprise landing at Menate, three miles behind the enemy, having been carried across the floods in a new type of amphibious troop-carrying tank called the Buffalo, which had come by sea from an advanced base in the Adriatic. By the 14th there was good news all along the Eighth Army front. The Poles took Imola. The New Zealand Division crossed the Sillaro. The 78th Division, striking north, took the bridge at Bastia and joined the attacks of the 56th on the Argenta road. The Germans knew well that this was their critical hinge and fought desperately.

That same day the Fifth Army began the centre attack west of the Pistoia-Bologna road. After a week of hard fighting, backed by the full weight of the Allied Air Forces, they broke out from the mountains, crossed the main road west of Bologna, and struck north. On the 20th Vietinghoff, despite Hitler’s commands, ordered a withdrawal. He tactfully reported that he had “decided to abandon the policy of static defence and adopt a mobile strategy.” It was too late.

Argenta had already fallen and the 6th British Armoured Division was sweeping towards Ferrara. Bologna was closely threatened from the east by the Poles and from the south by the 34th U.S. Division. It was captured on April 21, and here the Poles destroyed the renowned 1st German Parachute Division. The Fifth Army pressed towards the Po, with the tactical air force making havoc along the roads ahead. Its 10th U.S. Mountain Division crossed the river on the 23d, and the right flank of the Army, the 6th South African Division, joined the left of the Eighth. Trapped behind them were many thousand Germans, cut off from

Triumph and Tragedy

620

retreat, pouring into prisoners’ cages or being marched to the rear. The offensive was a fine example of concerted land and air effort, wherein the full strength of the strategical and tactical air forces played its part. Fighter-bombers destroyed enemy guns, tanks, and troops; light and medium bombers attacked the lines of supply, and our heavy bombers struck by day and night at the rear installations.

We crossed the Po on a broad front at the heels of the enemy. All the permanent bridges had been destroyed by our Air Forces, and the ferries and temporary crossings were attacked with such effect that the enemy were thrown into confusion. The remnants who struggled across, leaving all their heavy equipment behind, were unable to reorganise on the far bank. The Allied armies pursued them to the Adige. Italian Partisans had long harassed the enemy in the mountains and their back areas. On April 25 the signal was given for a general rising, and they made widespread attacks. In many cities and towns, notably Milan and Venice, they seized control. Surrenders in Northwest Italy became wholesale. The garrison of Genoa, four thousand strong, gave themselves up to a British liaison officer and the Partisans. On the 27th the Eighth Army crossed the Adige, heading for Padua, Treviso, and Venice, while the Fifth, already in Verona, made for Vicenza and Trento, its left extending to Brescia and Alessandria.

The naval campaign, though on a much smaller scale, had gone equally well. In January the ports of Split and Zadar had been occupied by the Partisans, and coastal forces from these bases harassed the Dalmatian shore and helped Tito’s steady advance. In April alone at least ten

Triumph and Tragedy

621

actions were fought at sea, with crippling damage to the enemy and no loss of British ships.

The Navy had operated on both flanks during the final operations. On the west coast British, American, and French forces were continually in action, bombarding and harassing the enemy, driving off persistent attacks by light craft and midget submarines, and clearing mines in the liberated ports. These activities led to the last genuine destroyer action in the Mediterranean. The former Yugoslav destroyer

Premuda,

captured by the Italians at the beginning of the war, left Genoa on the night of March 17, with two Italian destroyers, all manned by Germans, and tried to intercept a British convoy sailing from Marseilles to Leghorn. The British destroyers

Lookout

and

Meteor,

on patrol off the north point of Corsica, got warning and attacked. Both the Italian ships were sunk, the British suffering no loss or damage. By the time our armies reached the Adige the fighting at sea had virtually ended.