The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (21 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

But while it seems clear that the propensity for violence among young men lies partially in evolved psychological adaptations related to sexual competition, most men are not violent. So what factors explain why some societies seem better than others at preventing or controlling these impulses to violence?

INEQUALITY IS ‘STRUCTURAL’ VIOLENCE

The simple answer is that increased inequality ups the stakes in the competition for status: status matters even more. The impact of inequality on violence is even better established and accepted than the other effects of inequality that we discuss in this book.

203

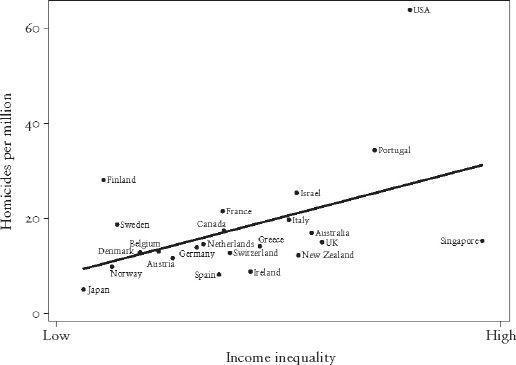

In this chapter we show relationships between violence and inequality for the same countries and the same time period as we use in other chapters. Many similar graphs have been published by other researchers, for other time periods or sets of countries, including one covering more than fifty countries between 1970 and 1994 from researchers at the World Bank.

207

,

210

A large body of evidence shows a clear relationship between greater inequality and higher homicide rates. As early as 1993, criminologists Hsieh and Pugh wrote a review which included thirty-five analyses of income inequality and violent crime.

211

All but one found a positive link between the two – as inequality increased so did violent crime. Homicides and assaults were most closely associated with income inequality, and robbery and rape less so. We have found the same relationships when looking at more recently published studies.

10

Homicides are more common in the more unequal areas in cities ranging from Manhattan to Rio de Janeiro, and in the more unequal American states and cities and Canadian provinces.

Figure 10.2 shows that international homicide rates from the United Nations

Surveys on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

212

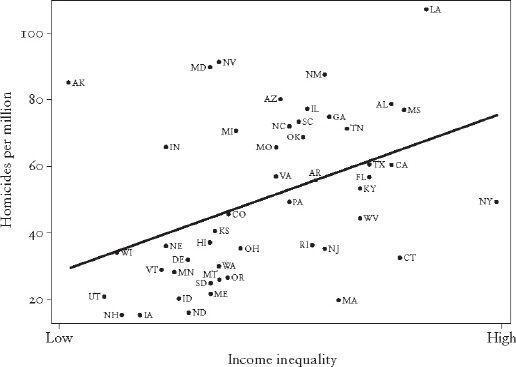

are related to income inequality, and Figure 10.3 shows the same relationship for the USA, using homicide rates from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

213

The differences between some countries in the first graph are very large. The USA is once again at the top of the league table of the rich countries. Its murder rate is 64 per million, more than four times higher than the UK (15 per million) and more than twelve times higher than Japan, which has a rate of only 5.2 per million. Two countries take rather unusual positions in this graph, compared to where they sit in many of our other chapters: Singapore has a much lower homicide rate than we might expect, and Finland has a higher rate. Interestingly, although international relationships between gun ownership and violent crime are complicated (for instance, gun ownership is linked to murders involving female victims but not male victims),

214

in the United Nations International Study on Firearm Regulation, Finland had the highest proportion of households with guns, and Singapore had the lowest rate of gun ownership.

215

Despite these exceptions, the trend for more unequal countries to have higher homicide rates is well established.

Figure 10.2

Homicides are more common in more unequal countries.

Figure 10.3

Homicides are more common in more unequal US states.

In the USA, although no data were available for Wyoming, the relationship between inequality and homicides is still significant and the differences between states are almost as great as the differences between countries. Louisiana has a murder rate of 107 per million, more than seven times higher than that of New Hampshire and Iowa, which are bottom of the league table with murder rates of 15 per million. The homicide rate in Alaska is much higher than we would expect, given its relatively low inequality, and rates in New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts are lower. In the United States, two out of every three murders are committed with guns, and homicide rates are higher in states where more people own guns.

216

Among the states on our graph, Alaska has the highest rate of gun ownership of all, and New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts are among the lowest.

217

If we allow for gun ownership, we find a slightly stronger relationship between inequality and homicides.

HAVENS IN A HEARTLESS WORLD

We have already seen some features of more unequal societies that help to tie violence to inequality – family life counts, schools and neighbourhoods are important, and status competition matters.

In Chapter 8 we mentioned a study which found that divorce rates are higher in more unequal American counties. In his book,

Life Without Father

, sociologist David Popenoe describes how 60 per cent of America’s rapists, 72 per cent of juvenile murderers and 70 per cent of long-term prisoners grew up in fatherless homes.

218

The effect of fatherlessness on delinquency and violence is only partly explained by these families being poorer. Why do fathers matter so much?

One researcher has described the behaviour of boys and young men who grow up without fathers as ‘hypermasculine’, with boys engaging in ‘rigidly overcompensatory masculine behaviors’

219

, pp. 1–2

– crimes against property and people, aggression and exploitation and short-term sexual conquests. This could be seen as the male version of the quantity versus quality strategy in human relationships that we described in relation to teenage mothers in Chapter 9. The absence of a father may predispose some boys to a different reproductive strategy: shifting the balance away from long-term relationships and putting more emphasis on status competition.

Fathers can, of course, act as positive role models for their sons. Fathers can teach boys, just by being present in the family, the positive aspects of manhood – how to relate to the opposite sex, how to be a responsible adult, how to be independent and assertive, yet included with, and connected to, other people. Particularly important is the way in which fathers can provide authority and discipline for teenage boys; without that security, young men are more influenced by their peers and more likely to engage in the kinds of anti-social behaviour so often seen when groups of young men get together. But fathers can also be negative role models. One study found that, although children had more behavioural problems the

less

time they had lived with their fathers, this was not true when the fathers themselves had behavioural problems.

220

If the fathers engaged in anti-social behaviour, then their children were at higher risk when they spent

more

time living with them.

Perhaps most importantly, fathers love their children in a way that studies show step-parents do not. This is not, of course, to say that most step-fathers and other men don’t lovingly raise other men’s children, but on average children living with their biological fathers are less likely to be abused, less likely to be delinquent, less likely to drop out of school, less likely to be emotionally neglected. Psychiatrist Gilligan says of the violent men he worked with

201

, p. 36.

They had been subjected to a degree of child abuse that was off the scale of anything I had previously thought of describing with that term. Many had been beaten nearly to death, raped repeatedly or prostituted, or neglected to a life-threatening degree by parents too disabled to care for their child. And of those who had not experienced these extremes of physical abuse or neglect, my colleagues and I found that they had experienced a degree of emotional abuse that had been just as damaging . . . in which they served as the scapegoat for whatever feelings of shame and humiliation their parents had suffered and then attempted to rid themselves of by transferring them onto their child, by subjecting him to systematic and chronic shaming and humiliation, taunting and ridicule.

The increased family breakdown and family stress in unequal societies leads to inter-generational cycles of violence, just as much as inter-generational cycles of teenage motherhood.

Of course it isn’t just the family environment that can breed shame, humiliation and violence. Children experience things in their schools and in their neighbourhoods that influence the probability that they will turn to violence when their status is threatened. The American high-school massacres have shown us the significance of bullying as a trigger to violence.

221

–

222

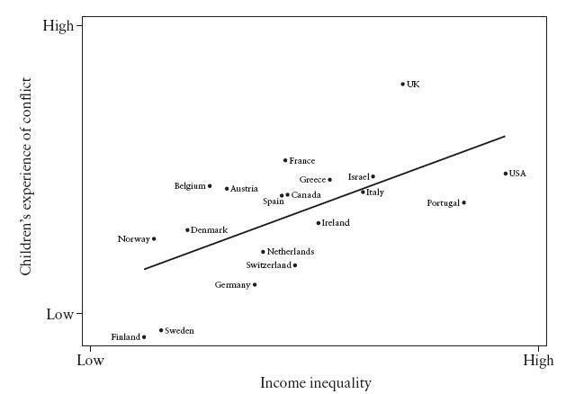

In UNICEF’s 2007 report on child wellbeing in rich countries, there are measures of how often young people in different countries were involved in physical fighting, had been the victim of bullying, or found their peers were not ‘kind and helpful’.

110

We combined these three measures into an index of children’s experiences of conflict and found that it was significantly correlated with income inequality, as shown in Figure 10.4. In more unequal societies children experience more bullying, fights and conflict. And there is no better predictor of later violence than childhood violence.

Environmental influences on rates of violence have been

Figure 10.4

There is more conflict between children in more unequal countries (based on percentages reporting fighting, bullying and finding peers not kind and helpful).

Israel recognized for a long time. In the 1940s, sociologists of the Chicago School described how some neighbourhoods had persistent reputations for violence over the years – different populations moved in and out but the same poor neighbourhoods remained dangerous, whoever was living in them.

223

In Chicago, neighbourhoods are often identified with a particular ethnic group. So a neighbourhood which might once have been an enclave of Irish immigrants and their descendants later becomes a Polish community, and later still a Latino neighbourhood. What the Chicago school sociologists drew attention to was the persistent effect of deprivation and poverty in poor neighbourhoods – on whoever lived there. In neighbourhoods where people can’t trust one another, where there are high levels of fear and groups of youths hanging around on street corners, neighbours won’t intervene for the common good – they feel helpless in the face of public disturbance, drug dealing, prostitution, graffiti and litter. Sociologist Robert Sampson and colleagues at Harvard University have shown that violent crime rates are lower in cohesive neighbourhoods where residents have close ties with one another and are willing to act for the common good, even taking into account factors such as poverty, prior violence, the concentration of immigrants and residential stability.

224

In the USA poor neighbourhoods have become ghettos, ring-fenced and neglected by the better-off who move out.

225