The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (9 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Community life and social relations

Among the new objects that attracted my attention during my stay in the United States, none struck me with greater force than the equality of conditions. I easily perceived the enormous influence that this primary fact exercises on the workings of the society.

Alexis de Tocqueville,

Democracy in America

In August 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast of the southern United States, devastating cities in Mississippi and Louisiana, overwhelming flood protection systems, and leaving 80 per cent of the city of New Orleans under water. A mandatory evacuation order was issued for the city the day before the storm hit, but by that time most public transport had shut down and fuel and rental cars were unavailable. The city government set up ‘refuges of last resort’ for people who couldn’t get out of New Orleans, including the Superdome, a vast sports arena, which ended up sheltering around 26,000 people, despite sections of its roof being ripped off by the storm. At least 1,836 people were killed by the hurricane, and another 700 people were missing and unaccounted for.

What captured the attention of the world’s media in the aftermath of the storm as much as the physical devastation – the flattened houses, flooded streets, collapsed highways and battered oil rigs – was what seemed like the complete breakdown of civilization in the city. There were numerous arrests and shoot-outs throughout the week following the hurricane. Television news screens showed desperate residents begging for help, for baby food, for medicine, and then switched to images of troops, cruising the flooded streets in boats – not evacuating people, not bringing them supplies, but, fully armed with automatic weapons, looking for looters.

This response to the chaos in New Orleans led to widespread criticism and condemnation within the US. Many alleged that the lack of trust between law enforcement and military forces on the one hand and the mostly poor, black citizens of New Orleans on the other, reflected deeper issues of race and class. During a widely televised benefit concert for victims of the hurricane, musician Kanye West, burst out: ‘I hate the way they portray us in the media. You see a white family, it says, “They’re looking for food.” You see a black family, it says, “They’re looting.”’ As troops were mobilized to go into the city, Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco said: ‘They have M16s and are locked and loaded. These troops know how to shoot and kill and I expect they will.’

The lack of trust on display during the rescue efforts in New Orleans was also roundly condemned internationally. Countries around the world offered aid and assistance, while their news coverage was filled with criticism. We can contrast the way in which troops in New Orleans seemed to be used primarily to control the population, with the rapid deployment of unarmed soldiers in rescue and relief missions in China after the devastating earthquake of 2008, a response widely applauded by the international community.

THE EQUALITY OF CONDITIONS

A very different vision of America is offered by one of its earliest observers. Alexis de Tocqueville travelled throughout the United States in 1831.

23

He met presidents and ex-presidents, mayors, senators and judges, as well as ordinary citizens, and everywhere he went he was impressed by the ‘equality of conditions’ (p. 11), ‘the blending of social ranks and the abolition of privileges’ – the way that society was ‘one single mass’ (p. 725) (at least for whites). He wrote that ‘Americans of all ages, conditions, and all dispositions constantly unite together’ (p. 596), that ‘strangers readily congregate in the same places and find neither danger nor advantage in telling each other freely what they think’, their manner being ‘natural, open and unreserved’ (p. 656). And de Tocqueville points out the ways in which Americans support one another in times of trouble:

Should some unforeseen accident occur on the public highway, people run from all sides to help the victim; should some family fall foul of an unexpected disaster, a thousand strangers willingly open their purses . . . (p. 661)

De Tocqueville believed that the equality of conditions he observed had helped to develop and maintain trust among Americans.

WHAT’S TRUST GOT TO DO WITH IT?

But does inequality corrode trust and divide people – government from citizens, rich from poor, minority from majority? This chapter shows that the quality of social relations deteriorates in less equal societies.

Inequality, not surprisingly, is a powerful social divider, perhaps because we all tend to use differences in living standards as markers of status differences. We tend to choose our friends from among our near equals and have little to do with those much richer or much poorer. And when we have less to do with other kinds of people, it’s harder for us to trust them. Our position in the social hierarchy affects who we see as part of the in-group and who as out-group – us and them – so affecting our ability to identify with and empathize with other people. Later in the book, we’ll show that inequality not only has an impact on how much we look down on others because they have less than we do, but also affects other kinds of discrimination, such as racism and sexism, with attitudes sometimes justified by statements like ‘they just don’t live like us’.

De Tocqueville understood this point. A lifelong opponent of slavery, he wrote about the exclusion of both African-Americans and Native Americans from the liberty and equality enjoyed by other Americans.

23

Slavery, he thought, could only be maintained because African-Americans were viewed as ‘other’, so much so that ‘the

European is to other races what man himself is to the animals’ (p. 371). Empathy is only felt for those we view as equals, ‘the same feeling for one another does not exist between the different classes’ (p. 650). Prejudice, thought de Tocqueville, was ‘an imaginary inequality’ which followed the ‘real inequality produced by wealth and the law’ (p. 400).

Early socialists and others believed that material inequality was an obstacle to a wider human harmony, to a universal human brotherhood, sisterhood or comradeship. The data we present in this chapter suggest that this intuition was sound: inequality is divisive, and even small differences seem to make an important difference.

INCOME INEQUALITY AND TRUST

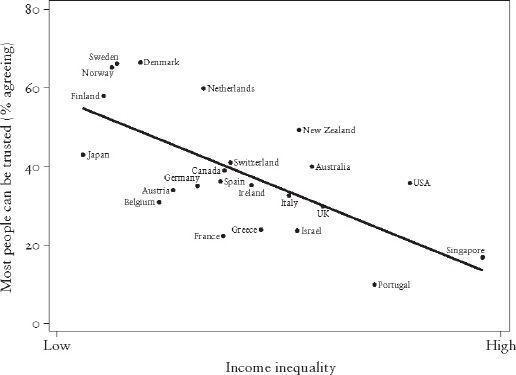

Figures 4.1 and 4.2 show that levels of trust between members of the public are lower in countries and states where income differences are larger. These relationships are strong enough that we can be confident that they are not due to chance. The international data on trust in Figure 4.1 come from the European and World Values Survey, a study designed to allow international comparisons of values and norms.

5

In each country, random samples of the population were asked whether or not they agreed with the statement: ‘Most people can be trusted.’ The differences between countries are large. People trust each other most in the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands; Sweden has the highest levels of trust, with 66 per cent of people feeling that they can trust others. The lowest level of trust is seen in Portugal, where only 10 per cent of the population believe that others can be trusted. So just within these rich, market democracies, there are more than sixfold differences in levels of trust, and, as the graph shows, high levels of trust are linked to low levels of inequality.

Figure 4.1

The percentage of people agreeing that ‘most people can be trusted’ is higher in more equal countries.

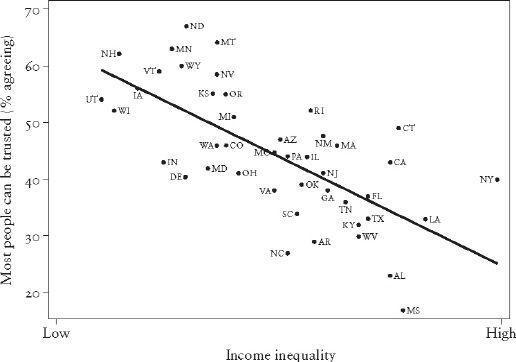

Figure 4.2

In more equal states more people agree that ‘most people can be trusted’. (Data available for only forty-one US states.)

The data on trust within the USA, shown in Figure 4.2, are taken from the federal government’s

General Social Survey

, which has been monitoring social change in America for more than a quarter of a century.

24

In this survey, just as in the international surveys, people are asked whether or not they agree that most people can be trusted. Within the USA, there are fourfold differences in trust between states. North Dakota has a level of trust similar to that of Sweden – 67 per cent feel they can trust other people – whereas in Mississippi only 17 per cent of the population believe that people can be trusted. Just as with the international data, low levels of trust among the United States are related to high inequality.

The important message in these graphs of trust and inequality is that they indicate how different life must feel to people living in these different societies. Imagine living somewhere where 90 per cent of the population mistrusts one another and what that must mean for the quality of everyday life – the interactions between people at work, on the street, in shops, in schools. In Norway it is not unusual to see cafés with tables and chairs on the pavement and blankets left out for people to use if they feel chilly while having a coffee. Nobody worries about customers or passers-by stealing the blankets. Many people feel nostalgic for time past, when they could leave their doors unlocked, and trusted that a lost wallet would be handed in. Of all large US cities, New Orleans is one of the most unequal. This was the background to the tensions and mistrust in the scenes of chaos after Hurricane Katrina that we described above.

CHICKEN OR EGG?

In the USA, trust has fallen from a high of 60 per cent in 1960, to a low of less than 40 per cent by 2004.

24

But does inequality create low levels of trust, or does mistrust create inequality? Which comes first? Political scientist Robert Putnam of Harvard University, in his book

Bowling Alone

, shows how inequality is related to ‘social capital’, by which he means the sum total of people’s involvement in community life.

25

He says:

Community and equality are mutually reinforcing . . . Social capital and economic equality moved in tandem through most of the twentieth century. In terms of the distribution of wealth and income, America in the 1950s and 1960s was more egalitarian than it had been in more than a century . . . those same decades were also the high point of social connectedness and civic engagement. Record highs in equality and social capital coincided . . . Conversely, the last third of the twentieth century was a time of growing inequality

and

eroding social capital . . . The timing of the two trends is striking: Sometime around 1965–70 America reversed course and started becoming both less just economically and less well connected socially and politically. (p. 359)