The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (19 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

WHY IT MATTERS

The press furore brings society’s fears and concerns around teenage motherhood into sharp focus. Often described as ‘babies having babies’, teenage motherhood is seen as bad for the mother, bad for the baby and bad for society.

There is no doubt that babies born to teenage mothers are more likely to have low birthweight, to be born prematurely, to be at higher risk of dying in infancy and, as they grow up, to be at greater risk of educational failure, juvenile crime and becoming teenage parents themselves.

172

–

173

Girls who give birth as teenagers are more likely to be poor and uneducated. But are all the bad things associated with teenage birth really caused by the

age

of the mother? Or are they simply a result of the cultural world in which teenage mothers give birth?

This issue is hotly debated. On the one hand, some argue that teenage motherhood is

not

a health problem because young age is not in itself a cause of worse outcomes.

174

In fact, among poor African-Americans, cumulative exposure to poverty and stress across their lifetimes compromises their health to such an extent that their babies do better if these women have their children at a young age.

175

–

176

This idea is known as ‘weathering’ and suggests that, for poor and disadvantaged women, postponing pregnancy until later ages doesn’t actually mean that they have healthier babies. Others have shown that the children of teenage mothers are more likely to end up excluded from mainstream society, with worse physical and emotional health and more deprivation. This is true even after taking account of other childhood circumstances such as social class, education, whether the parents were married or not, the parents’ personalities, and so on.

177

But although we can sometimes separate out the influences of maternal age and economic circumstances in research studies, in real life they often seem inextricably intertwined and teenage motherhood is associated with an inter-generational cycle of deprivation.

178

But how exactly are young women’s individual experiences and choices – their personal choices about sleeping with their boyfriends, choices around contraception and abortion, choices about qualifications and careers, shaped by the society they live in? Like the issues discussed in earlier chapters, the teenage birth rate is strongly related to relative deprivation and to inequality.

BORN UNEQUAL

There are social class differences in both teenage

conceptions

and

births

but the differences are smaller for conceptions than for births, because middle-class young women are more likely to have abortions. Teenage birth rates are higher in communities that also have high divorce rates, low levels of trust and low social cohesion, high unemployment, poverty, and high crime rates.

173

It has been suggested by others that teenage motherhood is a choice that women make when they feel they have no other prospects for achieving the social credentials of adulthood, such as a stable intimate relationship or rewarding employment.

179

Sociologist Kristin Luker claims that it is ‘the discouraged among the disadvantaged’ who become teenage mothers.

180

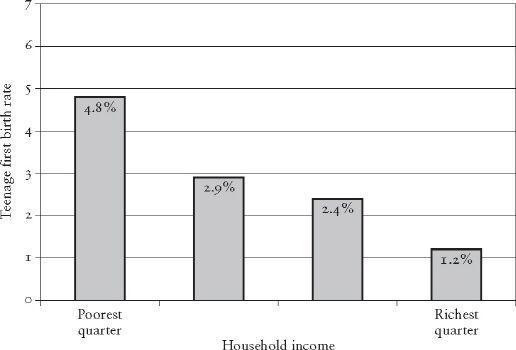

But it is important to remember that it isn’t only poor young women who become teenage mothers: like all the problems we have looked at, inequality in teenage birth rates runs right across society. In Figure 9.1, we show the percentage of young British women who become teenage mothers in relation to household income. Each year almost 5 per cent of teenagers living in the poorest quarter of homes have a first baby, four times the rate in the richest quarter. But even in the second richest quarter of households the rate is double that of the richest quarter (2.4 per cent and 1.2 per cent). Similar patterns are seen in the United States. Although most of these births are to older teenagers, aged 18–19 years, the pattern is evident, and even stronger, for the 15–17-year-olds.

Figure 9.1

There is a gradient in teenage birth rates by household income, from poorest to richest.

181

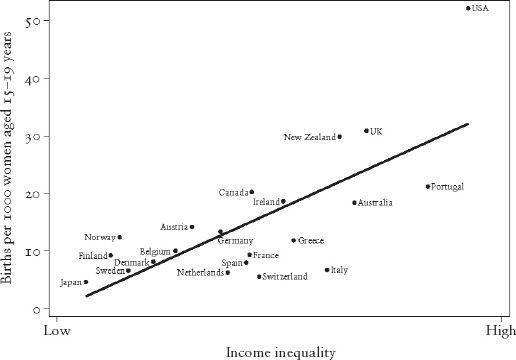

Figure 9.2

Teenage birth rates are higher in more unequal countries.

185

Figure 9.2 shows that the international teenage birth rates provided by UNICEF

182

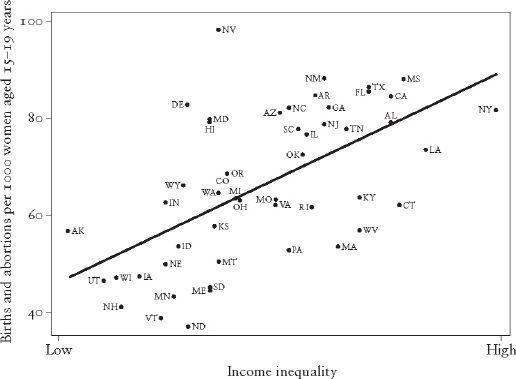

are related to income inequality and Figure 9.3 shows the same relationship for the fifty states of the USA, using teen pregnancy rates from the US National Vital Statistics System

183

and the Alan Guttmacher Institute.

184

There is a strong tendency for more unequal countries and more unequal states to have higher teenage birth rates – much too strong to be attributable to chance. The UNICEF report on teenage births showed that at least one and a quarter million teenagers become pregnant each year in the rich OECD countries and about three-quarters of a million go on to become teenage mothers.

182

The differences in teen birth rates between countries are striking. The USA and UK top the charts. At the top of the league in our usual group of rich countries, the USA has a teenage birth rate of 52.1 (per 1,000 women aged 15–19), more than four times the EU average and more than ten times higher than that of Japan, which has a rate of 4.6.

Rachel Gold and colleagues have studied income inequality and teenage births in the USA, and shown that teen birth rates are highest in the most unequal, as well as the most relatively deprived counties. She also reported that the effect of inequality was strongest for the youngest mothers, those aged 15–17 years.

186

For the US states, we show data for live births and abortions combined. There are substantial differences in pregnancy rates between US states. Mississippi has a rate close to twice that of Utah.

Figure 9.3

Teenage pregnancy rates are higher in more unequal US states.

We might expect patterns of conceptions, abortions and births to be influenced by factors such as religion and ethnicity. We’d expect predominantly Catholic countries to have high rates of teenage births, because of low rates of abortion. But, while predominantly Catholic Portugal and Ireland have high rates that would indeed fit this alternative explanation, Italy and Spain have unexpectedly low rates, although they are also predominantly Catholic. Within countries, different ethnic groups can have different cultures and values around sexuality, contraception, abortion, early marriage and women’s roles in society. In the USA, for example, Hispanic and African-American girls are almost twice as likely to be teenage mothers as white girls, and in the UK similarly, comparatively high rates are seen in the Bangladeshi and Caribbean communities.

182

But, because these communities are minority populations, these differences don’t actually have much impact on the ranking of countries and states by teenage pregnancy or birth rates, and so don’t affect our interpretation of the link with inequality.

But hidden within the simple relationships revealed in Figures 9.2 and 9.3 are the real-life complexities of what it means to be a teenage mother in any particular country. For example, in Japan, Greece and Italy, more than half of the teenagers giving birth are married – in fact in Japan, 86 per cent of teen mothers are married, whereas in the USA, the UK and New Zealand, less than a quarter of these mothers are married.

182

So not only do these latter countries have higher overall rates of teen births, but those births are more likely to be associated with the broad range of health and social problems that we think of as typical consequences of early motherhood – problems that affect both the mother and the child. Within the USA, Hispanic teenage mothers are more likely to be married than those from other ethnic groups, but they are also more likely to be poor;

187

–

188

the same is true for Bangladeshis in the UK.

So what do we know about who becomes a teenage mother that can help us understand this particular effect of inequality?

THE FAST LANE TO ADULTHOOD

Interestingly, there is not much of a connection between

teenage

birth rates and birth rates for women of

all ages

in rich countries. The most unequal countries, the US, UK, New Zealand and Portugal, have much higher teenage birth rates relative to older women’s birth rates than the more equal countries, such as Japan, Sweden, Norway and Finland, which have teenage birth rates that are lower relative to the rates of birth of older women.

182

So whatever drives teenage birth rates up in more unequal countries is unconnected with the factors driving overall fertility. Unequal societies affect teenage childbearing in particular.

A report from the Rowntree Foundation called

Young People’s Changing Routes to Independence

, which compares how children born in 1958 and 1970 grew up, describes a ‘widening gap between those on the fast and the slow lanes to adulthood’.

189

In the slow lane, young people born into families in the higher socio-economic classes spend a long time in education and career training, putting off marriage and childbearing until they are established as successful adults. For young people on the fast track, truncated education often leads them into a disjointed pattern of unemployment, low-paid work and training schemes, rather than an ordered, upward career trajectory.

As sociologists Hilary Graham and Elizabeth McDermott point out, teenage motherhood is a pathway through which women become excluded from the activities and connections of the wider society, and a way in which generations become trapped by inequality.

190

But as well as the constraints that relative poverty imposes on life chances for young people, there seem to be additional reasons why teenage motherhood is sensitive to degrees of inequality in society.

EARLY MATURITY AND ABSENT FATHERS

The first of these additional reasons was touched on in Chapter 8, where we discussed the impact of inequality on family relationships and stress in early life. Experiences in early childhood may be just as relevant to teenage motherhood as the educational and economic opportunities available to adolescents. In 1991, psychologist Jay Belsky at the University of London and his colleagues proposed a theory, based on evolutionary psychology, in which experiences in early childhood would lead individuals towards either a

quantity

or a

quality

reproductive strategy, depending on how stressful their early experiences had been.

191

They suggested that people who learned, while growing up, ‘to perceive others as untrustworthy, relationships as opportunistic and self-serving, and resources as scarce and/or unpredictable’ would reach biological maturity earlier, be sexually active earlier, be more likely to form short-term relationships and make less investment in parenting. In contrast, people who grow up learning ‘to perceive others as trustworthy, relationships as enduring and mutually rewarding and resources more or less constantly available’ would mature later, defer sexual activity, be better at forming long-term relationships and invest more heavily in their children’s development.