The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (18 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Societies can do a lot to ameliorate the stresses on families and to support early childhood development. From the very start of life, some societies do more than others to promote a secure attachment between mother and infant through the provision of paid maternity leave for mothers who work. Using data on the duration of paid maternity leave, provided by the Clearinghouse on International Developments in Child, Youth and Family Policies at Columbia University, we found that more equal countries provided longer periods of paid maternity leave.

Sweden provides parental leave (which can be divided between mothers and fathers) with 80 per cent wage replacement until the child is 18 months old; a further three months can be taken at a flat rate of pay, and then another three months of unpaid leave on top of that. Norway gives parents (again either mother or father) a year of leave at 80 per cent wage replacement, or forty-two weeks at 100 per cent. In contrast, the USA and Australia provide no statutory entitlement to paid leave – in Australia parents can have a year of unpaid leave, in the USA, twelve weeks.

As well as allowing parental leave, societies can improve the quality of early childhood through the provision of family allowances and tax benefits, social housing, health care, programmes to promote work/life balance, enforcing child support payments and, perhaps most importantly, through the provision of high-quality early childhood education. Early childhood education programmes can foster physical and cognitive development, as well as social and emotional development.

160

–

162

They can alter the long-term trajectories of children’s lives, and cost-benefit analyses show that they are high-yield investments. In experiments, disadvantaged children who have received high-quality early childhood education are less likely to need remedial education, less likely to become involved in crime, and they earn more as adults.

160

All of this adds up to a substantial return on government investments in such programmes.

UNEQUAL LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES

So far we have described ways in which greater inequality may affect children’s development through its impact on family life and relationships. But there is also evidence of more direct effects of inequality on children’s cognitive abilities and learning.

In 2004, World Bank economists Karla Hoff and Priyanka Pandey reported the results of a remarkable experiment.

163

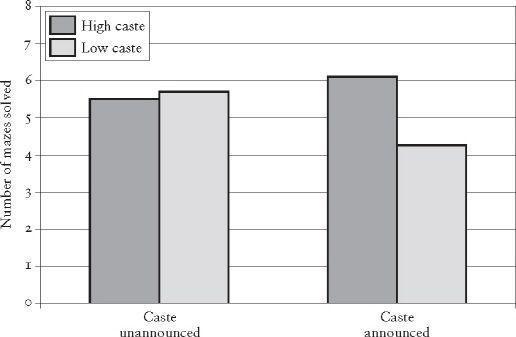

They took 321 high-caste and 321 low-caste 11 to 12-year-old boys from scattered rural villages in India, and set them the task of solving mazes. First, the boys did the puzzles without being aware of each other’s caste. Under this condition the low-caste boys did just as well with the mazes as the high-caste boys, indeed slightly better.

Then, the experiment was repeated, but this time each boy was asked to confirm an announcement of his name, village, father’s and grandfather’s names, and caste. After this public announcement of caste, the boys did more mazes, and this time there was a large caste gap in how well they did – the performance of the low-caste boys dropped significantly (Figure 8.5).

This is striking evidence that performance and behaviour in an educational task can be profoundly affected by the way we feel we are seen and judged by others. When we expect to be viewed as inferior, our abilities seem to be diminished.

The same phenomenon has been demonstrated in experiments with white and black high-school students in America, most convincingly by social psychologists Claude Steele at Stanford University, and Joshua Aronson at New York University.

164

In one study they administered a standardized test used for college students’ admission to graduate programmes. In one condition, the students were told that the test was a measure of ability; in a second condition, the students were told that the test was

not

a measure of ability. The white students performed equally under both conditions, but the black students performed much worse when they thought their ability was being judged. Steele and Aronson labelled this effect ‘stereotype threat’ and it’s now been shown that it is a general effect, which applies to sex differences as well as racial and ethnic differences.

165

Figure 8.5

The effect of caste identity on performance in Indian school boys.

163

Despite the work we mentioned on social anxiety and the effects of being judged negatively which we discussed in Chapter 3, it is perhaps surprising how easily stereotypes and stereotype threats are established, even in artificial conditions. Jane Elliott, an American schoolteacher, conducted an experiment with her students in 1968, in an effort to teach them about racial inequality and injustice.

166

She told them that scientists had shown that people with blue eyes were more intelligent and more likely to succeed than people with brown eyes, who were lazy and stupid. She divided her class into blue-eyed and brown-eyed groups, and gave the blue-eyed group extra privileges, praise and attention. The blue-eyed group quickly asserted its superiority over the brown-eyed children, treating them contemptuously, and their school performance improved. The brown-eyed group just as quickly adopted a submissive timidity, and their marks declined. After a few days, Elliott told the children she had got the information mixed up and that actually it was brown eyes that indicated superiority. The classroom situation rapidly reversed.

New developments in neurology provide biological explanations for how our learning is affected by our feelings.

167

We learn best in stimulating environments when we feel sure we can succeed. When we feel happy or confident our brains benefit from the release of dopamine, the reward chemical, which also helps with memory, attention and problem solving. We also benefit from serotonin which improves mood, and from adrenaline which helps us to perform at our best. When we feel threatened, helpless and stressed, our bodies are flooded by the hormone cortisol which inhibits our thinking and memory. So inequalities of the kind we have been describing in this chapter, in society and in our schools, have a direct and demonstrable effect on our brains, on our learning and educational achievement.

DIFFERENT STROKES FOR DIFFERENT FOLKS

Another way in which inequality directly affects educational achievement is through its impact on the aspirations, norms and values of people who find themselves lower down the social hierarchy. While education is viewed by the middle class and by teachers and policy makers as the way upwards and outwards for the poor and working class, these values are not always subscribed to by the poor and working class themselves.

In her 2006 book

Educational Failure and Working Class White Children in Britain

, anthropologist Gillian Evans describes the working-class culture of Bermondsey, in east London.

168

She shows how the kinds of activities expected of children in schools fit with the way middle-class parents expect their children to play and interact at home, but clash with the way in which working-class families care for, and interact with, their children. To a degree, working-class people resist the imposition of education and middle-class values, because becoming educated would require them to give up ways of being that they value. One woman tells Evans that being ‘common’ means ‘knowin’ ’ow to ’ave a good laugh ’cos you’re not stuck up’. The things that the women she describes like to talk about are their families, their health, work and ways to get money, housework, relationships, shopping, sex and gossip. Talking about abstract ideas, books and culture, is seen as posh and pretentious. The children of these working-class mothers are constrained by minimal rules in their homes. Evans describes children who are allowed to eat and drink what they like, when they like; to smoke at home; to do homework or not, as they please. ‘If they want to learn, they will, if they don’t, they won’t and that’s that.’ Of course these families want the best for their children, but that ‘best’ isn’t always ‘education, education, education’.

That poor and working-class children resist formal education and middle-class values does not, of course, mean that they have no aspirations or ambitions. In fact, when we first looked at data on children’s aspirations from a UNICEF report on childhood wellbeing,

110

we were surprised at its relationship to income inequality (Figure 8.6). More children reported low aspirations in more equal countries; in unequal countries children were more likely to have high aspirations. Some of this may be accounted for by the fact that in more equal societies, less-skilled work may be less stigmatized, in comparison to more unequal societies where career choices are dominated by rather star-struck ideas of financial success and images of glamour and celebrity.

Figure 8.6

Aspirations of 15-year-olds and inequality in rich countries.

In more unequal countries, we found a larger gap between aspirations and actual opportunities and expectations. If we compare Figure 8.1 on maths and reading scores in different countries to Figure 8.6, it is clear that aspirations are higher in countries where educational achievement is lower. More children might be aspiring to higher-status jobs, but fewer of them will be qualified to get them. If inequality leads to unrealistic hopes it must also lead to disappointment.

Gillian Evans quotes a teacher at an inner-city primary school, who summed up the corrosive effect of inequality on children:

These kids don’t know they’re working class; they won’t know that until they leave school and realize that the dreams they’ve nurtured through childhood can’t come true.

168

In the next two chapters we’ll show how young women and young men in more unequal societies respond to their low social status, and in Chapter 12 we’ll return to the theme of education and life chances when we examine the impact of inequality on social mobility.

Teenage births: recycling deprivation

Just saying ‘No’ prevents teenage pregnancy the way ‘Have a nice day’ cures chronic depression.

Faye Wattleton, Conference speech, Seattle, 1988

In the summer of 2005, three sisters hit the headlines of Britain’s tabloid newspapers – all three were teenage mothers. The youngest was the first of the girls to become pregnant and had her baby at the age of 12. ‘We were in bed at my mum’s house messing around and sex just sort of happened,’ she said; ‘I didn’t tell anyone because I was too scared and didn’t know what to do . . . I wish it had happened to someone else.’

169

Soon after, the next older sister had a baby at age 14. ‘It was just one of those things. I thought it would never happen to me,’ she said. ‘At first I wanted an abortion because I didn’t want to be like [my sister], but I couldn’t go through with it.’ The oldest sister, the last of the girls to find out she was pregnant, gave birth aged 16; unlike her sisters she seemed to welcome motherhood. ‘I left school . . . as I wasn’t really interested,’ she admitted, ‘all my friends were having babies and I wanted to be a mum, too’. At the time their stories became news, the girls were all living at home with their mother, sharing their bedrooms with their babies, the youngest two struggling with school, and all three trying to get by on social security benefits. With no qualifications and no support from the fathers of their babies, their futures were bleak. Media commentators and members of the public were quick to condemn the sisters and their mother, portraying them as feckless scroungers. ‘Meet the kid sisters . . . benefit bonanza’ . . . ‘Girls’ babies are the real victims,’ exclaimed the newspapers.

170

–

171

Their mother blamed the lack of sex education in school.