The Silver Spoon (6 page)

Authors: Kansuke Naka

The red sea bream looks beautiful,

42

and that its head carries the seven tools

43

and that Lord Ebisu

44

holds the fish in his arm makes a child happy. Its eyeballs are delicious. The outer layer is crumbly, but the core is soft yet unyielding, and no matter how long you chew on it, you can't chew it right up. When you spit it out, a semi-transparent ball drops on the plate with a clink. That its teeth are white is also good.

15

In those days there was a madman called Mr. So-and-So. Old folks said that when young he was obsessed with learning and always read books. Then he grew boastful of his scholarship, and went out of his mind. He let his hair grow wild and wore scorched rags on his body that looked almost scaly with grime and soot. Leaning on a thick bamboo cane, deep in thought, he quietly wandered about barefoot in winter or summer. When someone who remembered his past gave him rice balls and such, he would carry them home on his open palms as carefully as a priest holding an alms bowl. But if someone happened to give him something to wear, he would put it on with visible reluctance for one or two days, only to discard it for his rags.

He lived in a cave he had dug out near a farmhouse about two hundred yards away from us, and he kept a fire burning inside all year round. He would come out of the cave as he pleased and walk as far as he liked in whichever direction caught his fancy. When bored, he would simply turn on his heels to go home. Come rain or wind, he would be seen walking about in the neighborhood. As a result, when nobody saw him for a whole day, they said he must be in a bad mood, and when he didn't come out for three days, four days, they would wonder if he was well. Oddly, if he encountered a woman on the street, he would take a couple of steps back and spit as though he had seen something vile. My aunt, who was fastidious, had been concerned about the grubby, smelly man ever since she first saw him, and would hurriedly turn away before he had time to take his three steps back. One day, when on our way to the cheap cookie store we bumped into him, she couldn't take it any more.

“Would you kindly wash your face for me? I'll give you five pennies.” With these words she started to pull out her purse from her sash. The man looked taken aback and stopped. Then, shaking his head with great disgust, forgetting even to spit, he strode away.

This madman lived until I grew to be a normal kid. Then one day the rumor spread that he had been burned to death during the night. Although I was a bit afraid, I went to his cave, but all I saw was his bamboo cane and unburned kindling.

16

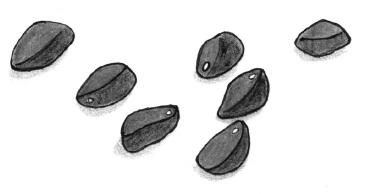

Saying she'd let me play Which-Nut,

45

my aunt would knock down nuts from a white camellia tree, although because she had poor eyesight and not much strength, she mainly slapped down twigs and leaves. Which-Nut was a game from her province; you chose camellia seeds of a certain shape, with players all putting out the same number, then taking turns to shake all their seeds in their hands before throwing them out on the tatami. The person with the greatest number of seeds with white bud spots showing won the round and all the seeds. Each seed had strengths and weaknesses depending on its shape and center of gravity. Some people, I was told, lacquered their seeds for adornment or slyly poured lead into them to strengthen them. You collect the nuts that were knocked down, and crack open their shells to find seeds shaped like a boat or a turnip, and sometimes shiny, all packed snugly into their compartments. They are called

mÅ, jÄ, toko, kai,

46

and such, according to their shape. I recall spending a whole quiet rainy day playing Which-Nut with several dozen seeds.

KINOMEDOCHI:

WHICH-NUT

Come summer, my aunt would point to clumps of clouds of various shapes that moved in the glittering sky overflowing with sunlight, telling me, as if it were all true, that that one was Lord Monju

47

or that one was Lord Fugen Bosatsu.

48

One day, tired of playing, I was lying by myself, waiting for a cloud shaped like a Buddha who would protect me to come along. However, the cloud that happened by, which looked like a Buddha lying supine, suddenly collapsed into such a terrifying form that I decided that a monster, assuming the form of a Buddha, had come to get me, and ran off to my aunt. From then on, I named the cloud of that particular shape a Dead Man's Buddha and, whenever I saw it, promptly hid myself.

Besides the weapons for the Yamazaki Battle, the leather basket also had toys in it, of which the drum and the

shÅ

49

were my special treasures. The black-painted pot of the

shÅ

had an arabesque lacquered on it. The long and short tubes arranged in a ring made soft, varying whistling sounds that gave my feeble nerves a pleasant sensation. The drum was small enough for my shoulder, and I liked everything about it, including its scarlet tuning cord and the interesting shape of its body. My invaluable aunt, who had dabbled in almost everything, would make me play the drum, while she herself played a larger drum on her knee in nice accompaniment.

Small items, such as a rabbit's paw made into a makeup brush, the “crane's beak” for rubbing the throat when a bone got stuck, and the brass mallet used to do something with sword-hilt ornaments, were all kept in what was called Kanpon's drawer in the cabinet with the many small drawers. I never volunteered to name which one I wanted. My aunt would take them out one by one while I whimpered, shaking my head, until she hit upon the right one. Even so, in most instances, if she took out the Divine Dog and the Rouge Ox, my mood would change for the better. Sometimes I would develop a dislike for something and toss it any which way. Even then she wouldn't lose her temper but, concerned that something might be wrong with me, put her hand on my forehead. If I had a temperature, I was taken to the doctor at once. I didn't like that, so if she put her hand on my forehead, I would visibly lose heart and grow quiet.

During the chrysanthemum season, she would pick chrysanthemums in the backyard and make a “chrysanthemum rug” to calm me. You spread on a sheet of paper various petals of different chrysanthemums like an Arabian design and press them. After a while you remove the press, and you have a fragrant rug. I liked chrysanthemum rugs very much.

At times I would dump out all the picture books filling my bookcase and make my endlessly patient aunt tell me one story after another. If I'd been scolded for something, after a good deal of weeping, I would then sulk. Angry at even those who, making an excuse of one kind or another, came to comfort me, I would console myself in a corner of a room, spreading picture books around me or playing with toys. At such times the Divine Dog, the Rouge Ox, the magic mallet, and the princess in the picture book, though they didn't say a word, soothed me with their kindness. Then I would become sorry for myself for having stopped weeping and tears would start flowing again. Sobbing, I would tell myself, “I don't care. I have all these friends,” while resenting everyone else.

17

At night I played with toys dumped in the dining room where my family was gathered. As you become sleepy, everything starts to get on your nerves. So if I began rubbing my eyes and fretting, it was time for my aunt to take me to bed.

“My, you've gotten sleepy,” she'd say and put away the toys littered all around and push my neck down to have me bow on the floor and say to everyone: “Be well and happy.”

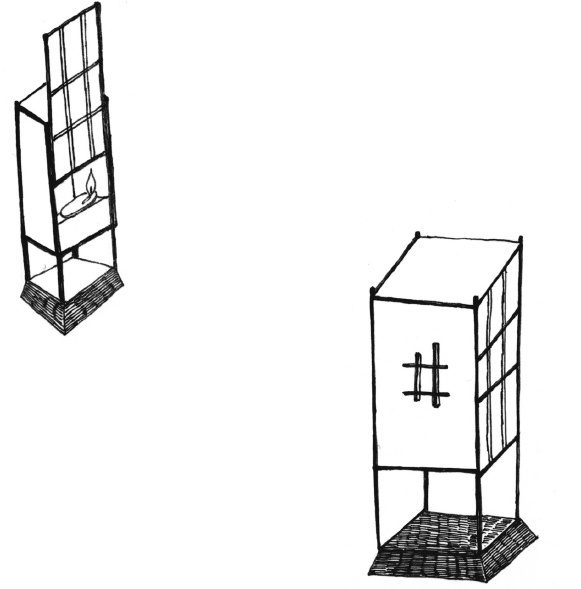

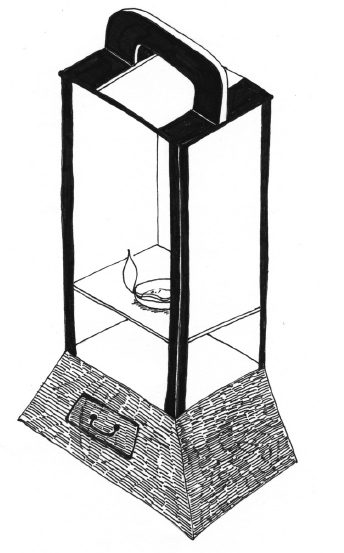

I would resist, protesting that I didn't want to sleep, yet I would eventually be pulled into the bedroom where my aunt used to sleep with me and the wet-nurse with my younger sister. At sunset the

andon

lantern

50

in the room was lighted and the bedding prepared

51

so that I could go to sleep as soon as my bad mood began to show. In winter my aunt would take a nightrobe from the several that had been left over the foot-warmer until they were almost warm enough to emit steam and exaggeratedly blow on it before tenderly wrapping my thin body in it. One of the coverlets had chrysanthemum figures, and another, probably imported from the West, the figures of golden-crested wrens and twigs on a maroon calico background. These coverlets held the fragrance of sunlight, and I loved to smell them, burying my face in their fluffy abundance.

ANDON:

LANTERNS

Since I was afraid of the dim light, after putting me into bed my aunt used to take out a new wick from the drawer attached to the lantern and add it. As she dipped the end of the new wick in the oil and put it next to the old one deeply sunken in oil, it would sparkle crisply and catch fire. Her hands would tremble as, with some difficulty, she pulled in the other end of the wick, which tended to stick out over the rim on the other side of the oil plate. Then from the spout of the oil pot she would pour amber-colored vegetable oil into the plate. The fluffy wick, the way it absorbed the oil, the shape of the wick holder, the smell of the burning oil, all such things. More than anything I disliked the corpses of insects lying black at the bottom of the oil and the burnt-out tip of the wick sticking to the rim of the plate. So, every day, after disposing of the used oil, she would scrape off the black wick tip with a blunt, broad-blade knife.

To this coward, the lantern was a little weird. From my bed where I lay with my sleepy eyes wide open, the spindle-shaped flame with the wick tip at its core looked like a goblin with a single long, narrow eye. As my aunt stuck her head inside the lantern to stir up the wick, almost burning her nose with the flame, her gigantic shadow reflected on the lantern paper made me wonder if she herself wasn't some kind of goblin.

Then my aunt, while putting the matches back in the drawer, would offer prayers for the souls of the insects who were lured to the light and burned to death. Once I couldn't sleep for fear that the Devil was lurking in the alcove ceiling where the light didn't reach. My aunt struggled to her feet and raised the lantern toward that part of the ceiling.

“See? No one's hiding up there.” In those days I believed the Devil was something scary-black with wild hair falling over itself.

“Call me if you get scared during the night,” my aunt would say. “You know I'm fierce. They'd all run away.”

Then she would tell stories until I fell asleep. She may not have been able to read any “square characters,” but she had heard and memorized an astonishing amount and knew an almost inexhaustible number of stories. Also, she had the knack of smoothly filling in the parts she'd forgotten with her own fanciful imagination. She gave different expressions and voices to different people, whether samurai or princesses, and would even put on the face of a monster for me which, in the dim light of the lantern, looked very real.

18

Among the most pitiful were the stories of the child who piles stones on the Riverbed of Sai

52

and the Hatsune drum of

The Thousand Cherry Trees.

My aunt would sing a snatch of that pilgrim's song in a sorrowful tone before adding explanations. I could not understand the whys and wherefores adequately, but a child who has troubled his mother just by being in her womb but has died before doing anything to repay his indebtedness is building a cairn to atone for the sin, piling stones forlornly on the Riverbed of Sai, when a demon comes along and harasses him by destroying the cairn with his iron cane. But then the gentle Lord JizÅ

53

protects him by hiding him under the sleeve of his robe. Each time I heard this story, I was oppressed with a suffocating gloom, the thought of the fate of the poor child making me sob uncontrollably. Aunt would rub me on the back, saying, “Don't worry, don't worry. There, we have the Lord JizÅ.”