The Silver Spoon (8 page)

Authors: Kansuke Naka

What she asked of the Lord Dainichi were things like “May this child be cured of his sickly body” and “May he not get hurt on the road,” which she would think of in advance for each date bearing the number eight.

On the fête day a host of beggars appeared and lined up along the temple fence. At the early hour we arrived, not all of them would be out; only a couple of quick ones among the cripples and the legless would be getting out thin straw mats and such. Slowly influenced by my aunt, I came to feel a vague but profound satisfaction with my childish compassion after giving them alms. Among the beggars was a good-looking blind woman who played the koto. Unlike now, not many people owned a koto back then, and my aunt and our wet-nurse often gossiped about her, saying that she must be what was left of someone who had once served a shogunate aide-de-camp or else a daimyo in the old days. She sang koto songs in a voice so crushed as to be almost inaudible. The way her plectrums skimmed and rolled over the strings with a light susurrus, and the way the bridges shaped like wild geese scattered over the wooden koto showing its cloud-like grain, were all new to me and beautiful.

23

If you went a little early, you could see the showmen setting up booths like spiders. Around them lay tools and boxes containing the creatures for the shows, which you looked at full of curiosity. Soon the picture boards would be put up. Most of them were eerie affairs like a goggle-eyed merman swimming in the sea and a large snake with a forked tongue about to swallow a chicken. But sometimes you saw a picture showing, on the blue board, numerous mice in kimono of different colors performing various tricks, holding in their hands fans with the rising sun painted on them. I liked that picture very much and went in to see the show each time it was put up. Many Nanjing mice came out to pull a cart and operate a well pulley. At the very end they carried tiny rice bags out of a papier-mâché storehouse and made a neat pile of them. The brown-mottled ones and snow-white ones scurrying around pell-mell were so cute. The trainer was a woman of about thirty, dressed like a female Westerner, with her hair bundled up and wearing a hat, still a very rare sight in those days. Every time a mouse carried out a rice bag, she would say rhythmically,

“Heave ho! Little one, bring it out!”

When a rice bag tumbled down from the paws of a hasty mouse toward the spectators, one of the children would pick it up at once and throw it back. The woman would say, “I thank you,” with a gracious smile and bow.

A rice bag often tumbled down toward me. I wanted to pick it up for her, but each time, though agitated, I could never put my hand out. The mice tricks done, the woman would produce a parrot from a red and blue striped cage and make him mimic her words. Usually the parrot would sit tamely on her palm and say whatever she wanted him to say. But when he was in a bad mood he would bristle his crown feathers and do nothing but screech. When that happened the woman would cock her head, looking lost, and say, “I don't know what's the matter with my dear TarÅ today.”

It was with regret that I would leave the booth, thinking about the picturesque parrot, his hooked beak, and his clever eyes.

24

Among the night stalls, the

hÅzuki

79

vendor was one thing that drew my heart. He would swivel a bamboo tube with a cogwheel attached to it, making a dull squeak.

MUSHIKAGO: INSECT CAGES

“HÅzuki yaa-i! HÅzuki!”

he would call.

On the coralline leaves spread upon a lattice lay red, blue, white, and various other

hÅzuki

dripping water. Round, fan-shaped

hÅzuki

, soul-shaped Korean

hÅzuki

, goblin

hÅzuki

, halberd

hÅzuki

âthese were all

hÅzuki

from the sea, each leathery bag carrying bilge that smelled of the beach. Tanba

hÅzuki

, thousand-cluster

hÅzuki

. The old man would swivel his bamboo tube and call out:

“HÅzuki yaa-i! HÅzuki!”

Since I couldn't make a sound with any of the plant

hÅzuki

, I always had them buy me the marine ones, which I would carry home, carefully clutched in my palms. The Tanba

hÅzuki

looks like a monk clad in a scarlet robe. When she peeled one and found a mosquito bite, my older sister would get mad and dash it to the tatami. The mosquito is an evil fellow. While the plant is still green, he secretly sucks out its sweet juice. One so damaged has a tiny star on its head, and while you knead it, its skin breaks.

In summer the stalls of insect vendors bewitched me. In cages shaped like fans, boats, and waterfowl, each with a scarlet tassel dangling beneath it, they kept pine insects

80

and bell insects

81

chirping, trilling. The katydid

82

chirps like someone pulling a sliding door, and the horse-bit insect

83

like a rustle of dead leaves. I wanted a pine insect or bell insect, but my aunt always bought me a katydid. Once to spite her I bought a rattler

84

which she hated, and she didn't sleep a wink that night. Rattlers came in a coarse bamboo cage, the four corner bars painted red and blue. If you put a slice of melon in the grille, they'd nibble on it, shaking their long antennae. They have puzzled expressions, and their incongruously long legs attached backward are funny.

Sometimes we bought pots of wildflowers. When bedtime came, my aunt would put them out under the eaves to expose them to the night dew. How can I describe a child's feelings as he looked at those flowers? It was a pure, innocent joy never to be felt again. Incited by the flowers, I would get up early the next morning and, still in my nightrobe and rubbing my eyes at the dazzling light, I would have a look. With tiny dewdrops lodging on the flowers and leaves, the velvety flowers of China pinks, heart's-ease with hairdo-shaped flowers, and pot marigolds were wide awake.

If you bought a picture book, they used to roll it and tie the middle with a strip of paper. Carrying it as if it were something fragile, I would take an occasional peek into the tube on my way home. Everyone would insist on seeing how beautiful the book was, and how important I felt as I slowly unrolled it for them. Everyone would marvel and say, I want it! I want it! Outside the picture frame on the cover, and in red ink, something like

Animals: New Edition

would be written. The smiling elephant with a long nose, the rabbit with pursed lips, the deer, and the sheep were all lovely. Though most of them were alone and looked quiet, the bear wrestled with the red KintarÅ,

85

and the wild boar whose snout thrust out like a bamboo shoot was held down by ShirÅ, of Nitan.

86

After proudly showing the book to all, I would say, “Be well and happy,” and go into the bedroom where my aunt would tell fabulous stories about the pictures. Finally I would look at the pictures all over again before putting the book near the pillow and falling asleep.

25

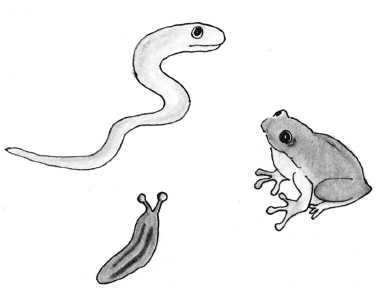

I was so timid I couldn't speak up when among people, and if I saw something I wanted all I did was stop walking, still holding onto my aunt's sleeve. My aunt, who knew this, would look around and ask questions. Until she hit upon the right thing I would simply go on shaking my head, but when it took too much time I would reluctantly point at what I wanted, only to put my finger shyly in my mouth. I loved the toy called “three scares,”

87

but my aunt disliked the snake and soon put it away when I wasn't looking. The bamboo rabbit jumped. On warm days its glue loosened and the rabbit, instead of jumping, would slowly raise its bottom and fall on its side. Besides these, the toys I liked were the bird in a cage that turned round and round, peeping, if you blew on the handle attached to its cage, and the “bream bow”

88

on which a fish slid down, its tail quivering delicately.

On windy winter nights, the fire of the

kantera

lamps in the roadside stalls sputtered desolately and the wicks looked like bloodshot eyes. At such times the person I pitied the most was an old woman selling raisin cakes. What the raisin cakes were I don't know. A shriveled-up woman of about seventy, she had a faded lantern with

Raisin Cakes

written on it and a few paper bags laid out on the small counter, but I never saw anyone buying them. I was truly sorry for her and pleaded with my aunt, but it was all so grimy that she wouldn't buy from her. Some years later when I was able to go out on fête days by myself, the old woman was still there, with her stall on the same corner near the noodle diner. Whenever a fair was on, I walked in front of her stall, back and forth, back and forth, tears brimming in my eyes. But each time I was unable to buy from her, and returned home, against my wishes. One night, however, I finally mustered my courage and approached the

Raisin Cakes

lantern. The old woman took me for a customer and picked up a paper bag.

SASUKUMI:

THREE SCARES

“May I help you?”

I did not know what to say, and before I knew what I was doing, I had thrown a two-

sen

coin on the counter and then ran to the shrubbery in the ShÅrin temple. My heart was pounding and my face burning.

I had no intention of going to “the fools' festival” at Lord Hachiman's.

89

This was because the fool's mask with a crushed nose, the

hyottoko

's

90

face whose eyes are topsy-turvy, and the too insistent, vulgar clown would sicken me. However, in their ignorant kindness, hoping it would cure my depression, my family, with even my aunt on their side, would try by any means to get me there. After I turned nine or ten, I would plead with them, saying it was painful to go to such a place. But they all thought it was just an excuse and would push me out of the house. When that happened, I went to a nearby field and, lying on my back on a cliff covered with large trees, spent my time watching the mountains.

26

Compared with the Kanda brats, the children in the new neighborhood were, as you might expect, much calmer, and the streets quieter, a world more suited to someone like me. So, my aunt tried very hard to find me a playmate, which she eventually did in O-Kuni-san, a girl on the other side of the street. (I have only recently learned that her father had been a samurai of the Awa fiefdom and a well-known loyalist

91

in those days.) Before anyone knew about it, my aunt had found out that O-Kuni-san was weak and quiet, even the fact that she had chronic headaches. She decided that therefore the girl could be just the right sort of friend for me. One day, she took me to an open area inside the gate of O-Kuni-san's house, where she was playing with some children, and, even though I resisted, put me down near them.

“He's a good boy. Would you play with him?”

For a moment the fun seemed to go out of the children, but soon they resumed their play with cheer.

That day it was for an “audience” only. Clinging to my aunt's sleeve, I watched them play for a while and came home. I was taken there the next day, too. In three or four days the children and I became used to each other somewhat, and when they laughed at something funny I showed a smile of sorts.

O-Kuni-san and her friends always danced “The Lotus Flower Has Bloomed.”

92

So my aunt patiently taught me the song and made me rehearse at home. When she decided I had mastered it, she took me inside the gate and, though I fretted, installed me beside O-Kuni-san. Seeing us two timid children shyly holding back, she tactfully inveigled us into placing our hands together, one palm upon the other, made our fingers bend, and then, giving them a squeeze from above, she finally succeeded in linking up the two hands. Until then I hadn't had a stranger hold my hand, so I was a bit afraid. Also, worried that my aunt might sneak away, I kept my eyes glued on her. The addition of this inharmonious newcomer totally spoiled the children's fun, and they wouldn't start turning. Observing this, my aunt joined the ring and, clapping her hands cheerfully, moving her feet rhythmically, and turning, she sang,