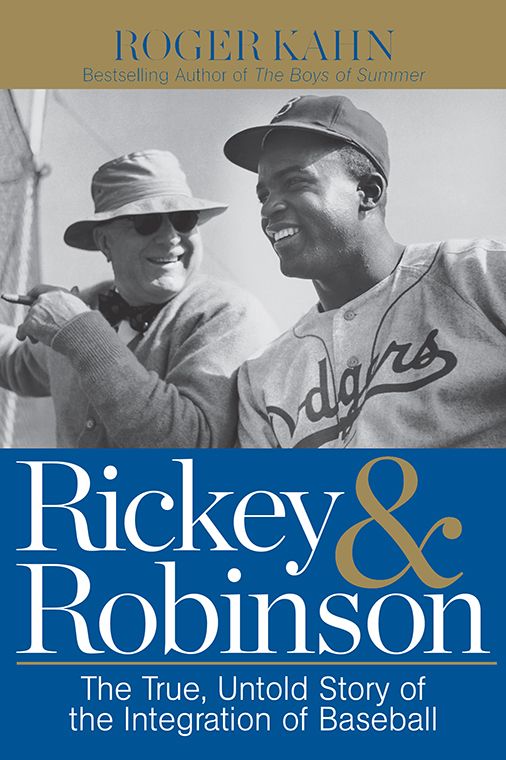

Rickey & Robinson

Authors: Roger Kahn

Also By Roger Kahn:

Into My Own, 2006

Beyond the Boys of Summer, 2005

October Men, 2003

The Head Game, 2000

A Flame of Pure Fire, 1999

Memories of Summer, 1997

The Era, 1993

Games We Used to Play, 1992

Joe and Marilyn, 1986

Good Enough to Dream, 1985

The Seventh Game, 1982

But Not to Keep, 1978

A Season in the Sun, 1977

How the Weather Was, 1973

The Boys of Summer, 1972

The Battle for Morningside Heights, 1970

The Passionate People, 1968

“Roger Kahn’s classic,

The Boys of Summer

, changed my life—that and

Catcher in the Rye

were the two books that made me dream of becoming a writer. Now, Roger returns to the Brooklyn Dodgers to breathe new life into the two familiar men who changed baseball and, in their own way, America. I thought I knew everything there was to know about Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson, but, not surprisingly, I’m still learning from Roger Kahn.”

—JOE POSNANSKI

Bestselling author of

The Soul of Baseball

and

The Machine

and national columnist for NBC Sports

“Branch Rickey signed me in 1946, a few months after his historical signing of Jackie Robinson. Jackie and I were teammates with the Dodgers for nine wonderful seasons, including the 1955 World Championship season later memorialized in Roger Kahn’s masterpiece,

The Boys of Summer

. But Mr. Rickey’s and Jackie’s baseball accomplishments pale in comparison to the cultural impact they had on America, an impact that reverberates to this day. Roger knew both men well—read his words and you will, too.”

—CARL ERSKINE

Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, 1948—1959, and author of

What I Learned from Jackie Robinson

“Much has been written about Jackie Robinson and much has been written about Branch Rickey. But, thanks to the legendary Roger Kahn, we are granted front-row access to the inner workings of a fascinating—and historic—relationship. Like its author,

Rickey & Robinson

is a treasure.”

—JEFF PEARLMAN

Bestselling author of

Showtime

and

The Bad Guys Won

“If you think you know the full Branch Rickey-Jackie Robinson story, you don’t. And you won’t until you read Roger Kahn’s

Rickey & Robinson

, which tells the tale in new, vivid, unvarnished ways. This, at last, is the definitive account.”

—WILL LEITCH

Author of

Are We Winning?

, senior writer for Sports On Earth and founder of Deadspin

For the incomparable Katharine

Who somehow suffers writers

.

Or anyway one writer

,

Gladly

.

“Adventure . . . All adventure”

The Battle Lines of the Republic

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF STEALS OF HOME BY JACKIE ROBINSON

“Adventure . . . All adventure”

IN 1903, WHEN BRANCH RICKEY WAS STARRING AS A catcher for the Ohio Wesleyan baseball team and coaching the squad though still a student, an incident erupted in South Bend, Indiana, that would change his life and, in time, change the country. The manager of the Oliver Hotel on West Washington Street said that Charles Thomas, Rickey’s black catcher who doubled as a first baseman, would not be permitted to register because “we don’t let in nigras.” That was one persistent and corrosive side of American life in 1903. Bigotry.

Rickey shouted down the hotel manager and dragged a cot into his own ground-floor room. Thomas would stay with him. Startled by Rickey’s intensity, the manager backed off. “But you gotta keep the colored boy downstairs,” he said. “He can’t go nowhere else. He can’t ride the elevators. And he sure as hell can’t eat with the white folks in our dining hall.” For emphasis the man slammed a fist on the counter.

Rickey turned away and took Thomas by an arm. “After we got into my room and I closed the door,” Rickey told me years later, “tears

welled in Charles’s large eyes. His shoulders heaved convulsively and he rubbed one great hand over another with all the strength and power of his body. He was muttering, ‘Black skin . . . black skin. If only I could make my black skin white.’”

Rickey’s sense of drama was extraordinary. He paused to let Thomas’s words and pain impact me. “Looking at Tommy that day,” Rickey said finally, “I resolved that somehow I was going to open baseball and all the rest of America to Negroes.” Large, assertive eyebrows moved closer together. Rickey bit his cigar and puffed a thundercloud of smoke. “It took me many decades, but I did it.”

“Forty-four years later,” I said. “When you signed Jackie Robinson, did you know how good a ballplayer he was going to be?” Many suggest that Rickey was the greatest talent scout in all of baseball history.

He made a rumbling laugh. “Adventure,” he said. “Adventure. Show me a ballplayer with a sense of adventure and I’ll show you a great one. Adventure, all adventure . . . that was the Jackie Robinson I signed.”

The implications of that signing and indeed the significance of Branch Rickey’s long life and of Jackie Robinson’s life, which was all too brief, transcend the game and the business of baseball. But wasn’t integration coming to America anyway? Wasn’t integration an irresistible wave of the American future, as women’s suffrage once had been? Possibly so. Perhaps even probably so. But before Rickey–Robinson, America’s movement toward integration was so slow as to be barely discernible.

Marian Anderson, the great black contralto, was barred from singing at the Metropolitan Opera until she was almost 60 years old. Paul Robeson, the matchless bass baritone, was hounded to death by right-wingers citing Robeson’s defiant, leftist politics. Arrant bigotry played a major role in the persecution of Robeson, who had also been one of the first blacks to play in the National Football League. Turning on Joe Louis, the hammering heavyweight champion, functionaries at the Internal Revenue Service demanded enormous payments in

Louis’s later years. They flatly refused to give him credit for the hundreds of thousands of dollars he had donated to Army and Navy family relief during World War II. Louis was careless with money, but government bigotry was a major reason that the Brown Bomber died broke and broken.

As Robinson told me on many occasions, “When you think about it, my demand was modest enough. I wasn’t asking to move into your neighborhood, or send my kids to school with your kids, and I certainly was not proposing to join your golf club. All I wanted was the right to make the kind of living that my abilities warranted.”

Obviously Rickey–Robinson could not and did not categorically end American bigotry, but they significantly diminished it. At the very least, they played a clear white light into corners that had been crawling and ugly. I used to say, “No Jackie Robinson, no Martin Luther King.” I expand that statement today. Without the foresight and the high moral purpose of Branch Rickey, and without the radiant courage of Jackie Robinson, Barack Obama could not have been elected president of the United States.

A nice touch to this rousing saga is the element of unpredictability. Close as I was to Jackie, intimate as I was with Branch, all the time I thought that the first minority American president would be a Jew.

—Roger Kahn

STONE RIDGE, NEW YORK

CONTRADICTIONS

L

IKE MOST OF US WHO TAKE WRITING AND BASE-ball seriously, Walter Wellesley “Red” Smith retained a soft spot in his portable typewriter and a valentine in his heart for Wesley Branch Rickey.

Mister

Rickey, as generations of ballplayers were required to call him, was the game’s greatest orator, a clubhouse Churchill, its preeminent theoretical thinker, its talent scout beyond compare and, most important in America’s social history, its noble integrator. Rickey’s polysyllabic eloquence made the craft of baseball writing easier. Quote him accurately and the eloquence edged into your own prose. That may be what inspired Smith when he created this enthusiastic and extraordinary paragraph.

Branch Rickey was a player, manager, executive, lawyer, preacher, horse-trader, spellbinder, innovator, husband and father and grandfather, farmer, logician, obscurantist, reformer, financier, sociologist, crusader, father confessor, checker shark, friend and fighter. Judas Priest, what a character.

Well aware of Rickey’s merits, a college professor named Judith Anne Testa, who wrote an excellent biography of the intimidating

pitcher Sal Maglie (whom she called “baseball’s demon barber”), raised an interesting question. “How,” Judy Testa asked when I was working on this book, “are you going to write something consistently interesting when one of your principal characters has no vice worse than smoking cigars?” It is true that Rickey neither drank nor caroused. He was unfailingly faithful to his wife, Jane, and to the Christian religion as he perceived it. He was a doting father to his diabetic son, Branch Rickey Jr., who in later years became, for whatever reasons, a heavy drinker. (Branch Jr. died at the age of 47.)

But there existed another side to the Mahatma. Rickey was a greed-driven man, obsessed across the nine decades of a remarkable life with amassing and guarding a personal fortune. He never once went to a ballpark on Sunday, citing a promise made to his mother always to observe the Christian Sabbath. That oath, however solemn, did not prevent him from banking the gate receipts of Sunday games.

His penury became legendary, notably among the men who played for him. “Mr. Rickey,” Enos Slaughter remarked to me one day at Cooperstown, “likes ballplayers. And he likes money. What he don’t like is the two of them getting together.”

A journeyman outfielder named Gene Hermanski hit 15 homers and batted .290 for the 1947 Dodgers. The following winter he strode into the team’s Brooklyn offices, where Bob Cooke of the

New York Herald Tribune

was loitering in search of a story. “This time,” Hermanski said to Cooke, “I’m gonna get the raise I deserve.” Half an hour later Hermanski emerged from Rickey’s presence smiling.

“You got the raise?” Cooke asked.

“No,” Hermanski said, “but he didn’t cut me.”

After the star-crossed pitcher, Ralph Branca, appeared in 16 games for the wartime Dodgers of 1945, Rickey offered him a 1946 contract calling for a salary of $3,500, which, on an annual basis, comes out to about $67 a week. Branca was only 20 years old, but locally prominent. He had been a two-sport (baseball and basketball) star at New

York University and possessed a good fastball and a snapping curve. He consulted with his older brother, John, himself a pretty fair pitcher and later a New York state assemblyman. John thought his kid brother deserved $5,000 and Ralph returned the contract unsigned with what he recalls as a courteous letter “to Mr. Rickey” requesting an additional $1,500.