The Rape of Europa (53 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The Army planners for Europe had already done all they were willing to do for art and were unwilling to create a slot for Newton. By now seventeen men had been designated for MFAA work under expanded rules, pushed by MacLeish and Fulbright, which would allow them to sequester movable works of art and seek information on looters. The Army felt it would be up to the civilians to decide after hostilities what would be done with the objects that were found and that this issue should not be a military problem.

But the Roberts Commission members at home were absolutely convinced that control of the vast numbers of works of art known to have changed hands would necessarily involve the Army, and continued their campaign to install their own man and circumvent Woolley, whom they correctly viewed as insufficiently interested in restitution problems which did not much affect Britain. Meanwhile, Met director Francis Henry Taylor, who had been dying to get into the fray from the beginning, managed to get Army approval to go to London later in the summer.

It was not until July 27, 1944, with the reconquest of France well under way, that RC members MacLeish and Dinsmoor (who had wangled a tour

of the Italian theater) reported back and told all. “These reports give us our first real news of what is going on abroad,” wrote Finley rather wistfully. The Commission particularly wanted fresh news which could be given to the press to enhance the American image. They were infuriated that Woolley had already been able to write articles on the events at hand, based to a large degree on work done by Americans, and publish these pieces in British periodicals months before they were fed their few paltry crumbs of information by the CAD. The stories, picked up by American magazines, naturally credited the British War Office.

Indeed, by July 1944, one month after D-Day, the RC had not yet received any field reports later than February from any theater, and these were so highly classified that they could not be published.

14

The day after these briefings they applied for clearance for yet another representative, Sumner Crosby, to go to London after Taylor. It was clearly necessary, as Hilldring had stated, to have someone of their very own there at all times.

This was further underlined by the fact that they had so far not heard anything from Newton, who, persuaded he could do nothing at SHAEF in London, and excluded from the invasion of France, had written his own orders and gone to Italy. There he was having a thoroughly good time, going around with the officers in the field and meeting important people. (He even managed to get an audience with the Pope and to present him with his third set of MFAA handbooks and maps, not realizing that both General Marshall and Dinsmoor had done so before.) Despite the distractions, Newton was writing perceptive letters and reports to the RC from Italy, but as he was required to send these through channels, they were not being passed on, and, in fact, the Commission did not even know where he was. Dinsmoor had only been able to report that when last heard of, Newton had been at sea, approaching Livorno. In early August, Finley, still in the dark, wrote to Assistant Secretary McCloy demanding assurance that “Col. Newton’s organization is now working effectively in England, and that an adequate number of officers have been assigned to France.”

15

New Yorker Taylor was making other waves in his efforts to deal with the government. Through the State Department he demanded that the Civil Affairs Division inform the SHAEF high command that “I am authorized by the Roberts Commission to advise them concerning fine arts personnel.”

16

This pronouncement went right across the normal channels of some five agencies, a definite Washington faux pas. To make things worse, General Julius Holmes, Deputy Chief of G-5, SHAEF, discovered Taylor in the lobby of the Hotel Crillon in Paris shortly after its liberation and long before any civilians were supposed to be there. Exasperated, he wrote Hilldring to say that he did “not know what we can do to calm these people

down.” Eisenhower, he said, “fully realizes both his short and long term responsibilities in this connection…. For your private ear I feel that this constant pushing has not helped matters in the slightest.”

17

Hilldring tattled to the RC and warned that “the inevitable result of civilian appearances in operational areas will be an order from the Theater Commander excluding them entirely.”

18

By now much permanent damage had been done: the Allied High Command and the Monuments men in the field had begun to regard the Roberts Commission less as an ally and more as a badly informed and interfering adversary.

Unpopular though all this might have been, the Commission was in fact beginning to make headway. Its pushy emissaries had brought back much interesting information. Taylor had managed to make contact with Jaujard and the French museums; he also had made a serious start on drafting a realistic restitution policy. From Jaujard and others he had heard of the immense trade and confiscations which were still going on in the shrinking Reich.

Through his Washington contacts he also knew enough to be quite sure that there would be no armistice resembling that of Versailles, as the occupied countries expected, but rather a “surrender to a Tripartite Supreme Authority,” i.e., Russia, Britain, and the United States. Allied advances were now so rapid that it was felt in the highest circles that Germany might collapse at any moment. Taylor, feeling that there was no time to waste, had already cabled home to ask that all the files compiled by the American committees be microfilmed and brought to London by the next RC emissary.

Meanwhile, post-surrender policy was being discussed in London by the European Advisory Council, an entity set up by Big Three foreign ministers in October 1943. Taylor and his colleagues were convinced that the ultimate fate of thousands of displaced works of art would depend on these deliberations, and they were determined to see that the United States was properly represented in any restitution decisions. To make sure of this, they opened an RC office in London with a staff of two, and arranged to keep a representative there full-time.

To get around the U.S. Army’s reluctance to supply intelligence, Taylor turned to a more sympathetic source: the OSS. Here was an organization which did not have to work through Army channels. Access was no problem—its ranks were full of friendly academics and the London office was headed by former National Gallery President David Bruce. Bruce had initiated contact with the Roberts Commission soon after his recruitment to the secret agency in 1942. He had wanted to have an OSS analyst attend RC meetings and had hoped to send agents into Europe under MFAA

cover, ideas that met with negative responses from everyone: Finley, Eisenhower, and the Army staff.

Ignoring these objections, Taylor began discussions with the OSS in London in August 1944. The idea of investigating Nazi looting not only appealed to the RC but fit in well with the OSS’s counterintelligence operation which was compiling dossiers on Nazi agents on the Continent who might be a threat after the German military forces had been defeated. The OSS, like the economic agencies, was interested in tracing and preventing the flow of assets to places of refuge where they might be used to finance the postwar survival of Nazism. And not least, the agency was beginning to compile evidence for future war crimes prosecutions. By late November 1944 an Art Looting Investigation Unit had been set up, staffed by art historians recommended by the Roberts Commission. They were technically listed as members of the armed forces, but “as members of an OSS unit… have facilities for movement both in military zones and neutral countries perhaps not fully enjoyed by the members of other services.”

19

Entirely separate from the Monuments men attached to the armies, they would report directly to the Commission.

Even this did not quiet the anti-Woolley obsession of the commissioners, whose information from the French front was still minimal, and who had finally recognized that Newton would never be persona grata at SHAEF headquarters. The CAD recognized this too and supported an additional civilian representative, indicating that despite his naughtiness Taylor would be “desirable.” But Taylor was not interested. Finley this time proposed someone who would be comfortable in the most eminent circles, military or otherwise, in the United States or Europe: the philanthropist and amateur art historian John Nicholas Brown.

Brown was no stranger to the preservation of monuments, having been involved in the restoration of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and various similar projects. His status was unusual: he was officially a civilian but was given the “simulated” title of lieutenant colonel, the equal of Woolley, and he would be in uniform. At meetings in Washington Brown was given the impression that he would be Special Cultural Adviser to Eisenhower and serve on his personal staff.

All these chauvinist turf wars might as well have been happening on the moon as far as the Allied combat forces were concerned. Eisenhower’s Great Crusade had finally begun. The free men of the world, he said, were marching together to victory. Incredibly, despite the millions of men involved in the planning of the invasion of Normandy, there had been no leaks, and the landing, cloaked by stormy weather, was a surprise to the

Germans, lulled, as their opponents had been before them, into complacency by a series of false alarms. On the afternoon of D-Day, June 6, 1944, Churchill reported to the House of Commons that all was going according to plan. By June 10 the Allies had taken a sufficient strip along the coast to allow Churchill and all the Chiefs of Staff to go across in a pair of destroyers and see the situation for themselves. It was a beautiful day. In the midst of the battle scenes, Churchill noticed that the fields were full of “lovely red and white cows basking or parading in the sunshine.” On the way home the happy PM had his destroyer sail down the coast so he could fire a few shots at the German positions. To Roosevelt, waiting anxiously in Washington, he wrote that he had had a “jolly day … on the beaches and inland,” and described the fifty-mile-long mass of shipping deployed along the coast as “stupendous.”

20

But after Italy they all knew this was just a beginning. It would not take the German armies long to consolidate their resistance.

The first Monuments officer ashore in France was a New York architect, Bancel LaFarge, who arrived in the first week after D-Day. Because of the enforcedly small size of his territory, centered on Bayeux, he was able to cover most of it in the first days on foot and by hitchhiking. Bayeux he found quite intact, and inhabited by the official architect of the Monuments Historiques, who was surprised to find that there were Monuments officers in the Allied armies. Among other things LaFarge learned the recent history of the Bayeux tapestry, which, he was told, had been removed to the repository at Sourches, also the refuge of a number of other important works from the Louvre. The existence of this repository, despite the secret messages acknowledged by the BBC, was news to LaFarge and he immediately sent it on to higher headquarters.

21

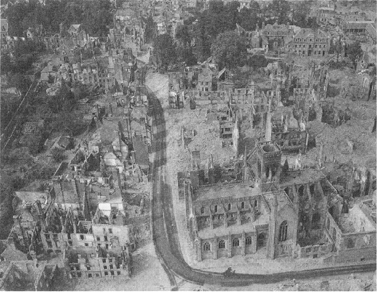

As the beachhead slowly expanded, other colleagues began to arrive. George Stout, in action at last, celebrated the Fourth of July anchored off Utah Beach; fireworks were provided by an enemy attack during the night. Intact Bayeux was not to prove typical of what he would soon encounter. For days before the fall of Caen the towers of its two great abbeys had been visible in the distance, raising hopes that the rest of the town might not be too badly damaged. But LaFarge and Stout found the city 70 percent destroyed by Allied bombing and the population very angry when they finally arrived there. In the next weeks, before the Allies broke through the German lines and began their headlong rush toward Paris and the Netherlands, such scenes would become the norm.

They could not at first believe the destruction. “So total is the ruin that a description, however strong, would be an understatement of the fact,” reported

British officer Dixon-Spain after seeing the little Calvados town of Vire. Saint-Lô, where the Germans had built trenches and bunkers in and among the old buildings, was worse, and not just because of the bombs. In the rubble of the tracery of the windows of the great Church of Notre Dame lay broken and rifled tabernacles and safes. Inside were stacks of “grenades, smoke bombs, ration boxes and every conceivable sort of debris. There were booby traps on the pulpit and the altar. At the entrance, a stick of dynamite was attached with string or wire to a piece of masonry wall which had fallen.”

22

Inside the thirteenth-century parish church in La Haye-du-Puits, James Rorimer discovered an intact German antiaircraft gun which had escaped destruction when Allied bombardiers, marked maps in hand, had carefully avoided bombing the historic edifice.

23

To save the remains of these shattered churches from zealous engineers and souvenir seekers, Stout cordoned off the ruins with the white tape used to indicate dangerous mined areas.

Other books

Kinkaid (Bad Boys of Retribution MC Book 2) by Warren, Rie

Reveal: A Contemporary Romance (Billionaire Rock Star Romance Book 2) by Love-Wins, Bella, Wild, Bella

Dust Up: A Thriller by Jon McGoran

Second Skin by Jessica Wollman

La última batalla by Bill Bridges

Godfather, The by Puzo, Mario

The Sudden Weight of Snow by Laisha Rosnau

Wolf Ties (A Rue Darrow Novel Book 2) by Audrey Claire

The Greatest Knight by Elizabeth Chadwick

No Rules by R. A. Spratt