The Rape of Europa (55 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

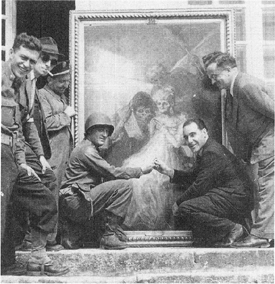

Rorimer meets Bazin at Sourches, before Goya’s

Time.

A few days later, Allied officers set off to check on the repository at Sourches and others in its vicinity. As they passed through the countryside, children ran out to offer them wine and fresh fruit. At Sourches they were met by Germain Bazin, who, to prevent bombing, had had his men put the enormous letters

MN

on the lawn. Fuel having run out, he had kept charcoal fires burning constantly in the cellars to control humidity. He had succeeded: despite all, the Rubens of the Medici Gallery, the enormous

Wedding at Cana

, and all the rest were intact. From Bazin, Rorimer and his colleagues heard all about the odious Abel Bonnard, and enough about the status of the rest of the national collections to feel that “it is not necessary to ask the French officials, as did the Germans, for complete lists of depositories and their contents.” The terrible responsibility for these collections would remain with the French.

32

The Western occupied countries had remained full of Germans until the very end. Supervision of German officials in France had largely been taken over by the SS chief General Oberg after the Commandant of Paris, von Stülpnagel, had committed suicide or been murdered after the July 20 coup attempt. But by the end of the first week of August 1944, the exodus was well under way. Chimneys again smoked in the summer heat as documents were burned. Parisians who up till now had remained maddeningly calm, limiting themselves to small provocations such as wearing red, white, and blue clothes on Bastille Day, became more overt in their display of feelings. Railroad workers went on strike. German civilians dragging huge bags to train stations could find no porters. Their requisitioned cars, grotesquely laden with the contents of their requisitioned apartments, developed strange engine problems and record numbers of flat tires. Even the Vichy powerful, who had made the most careful arrangements, were not immune: Abel Bonnard had arranged for a convoy of three cars to take himself, his aides, his family, and his files to safety in Germany. Alas, his chauffeur had been subverted by the Resistance, and the cars vanished. Bonnard had to appeal to his friend Abetz for a ride east.

33

The complex network of dealers began to unravel. Considerable effort now went into the saving of self and assets. Alois Miedl left Holland in July, heading for Spain. He took some twenty paintings with him and told his assistant to sena others to Berlin, where they were stored in three banks. (Miedl had already entrusted to a lawyer in Switzerland six of Paul

Rosenberg’s pictures that Hofer had kindly sold to him for a not inconsiderable sum.) Gustav Rochlitz waited until after D-Day to ship his remaining stocks, which included fifty-one of the paintings he had obtained through the ERR, off to five locations in Germany. He himself did not depart until August 20, only days before the fall of Paris. On July 13 Bruno Lohse wrote Hofer to tell him that Hugo Engel, Haberstock’s protégé, had fled, and that Haberstock now found himself “in difficulties.” But Lohse was still sufficiently businesslike to devote part of the letter to arrangements for the purchase of two sculptures for Goering.

34

What was left at the Jeu de Paume, “degenerate” and otherwise, was hastily packed in 148 cases and taken on August 1 to the railroad yards to be loaded onto a waiting train. Of the fifty-two cars, the ERR objects took up five; the rest of the space was reserved for a final shipment of miscellaneous items collected by von Behr’s M-Aktion. Rose Valland, just as indefatigable as von Behr, managed to record the numbers of the freight cars in which the ERR crates were packed. She informed Jaujard, who contacted Resistance elements in the French railways.

The train, fully loaded, sat on a siding next to dangerous gas storage tanks at the Ambervilliers station awaiting a slot on the jammed tracks heading back to the Reich. A week passed. After much fussing by von Behr the train finally left, but, alas, “because of its extremely heavy load” it developed “mechanical problems” which necessitated a forty-eight-hour stop at Le Bourget. Next it moved on to Aulnay, still in the suburbs of Paris, where it was put on another siding because it needed a new locomotive. It was still there on August 27 when a detachment of General Leclerc’s army, informed by railroad officials of the precious contents of the cars, captured the train and its guards. The commanding officer was Alexandre Rosenberg, Paul’s son, who had quite unknowingly recovered twenty-four Dufys, four Degas, three Lautrecs, eleven Vlamincks, ten Utrillos, sixty-four Picassos, twenty-nine Braques, twenty-five Foujitas, ten de Segonzacs, more than fifty Laurencins, eight Bonnards, and works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Modigliani, Renoir, and so on, many of which he had last seen in his own house.

35

The human occupants of the Jeu de Paume had also left on August 16 with the main body of the German occupation government, in considerable panic at the news that they might be liable for active military duty within forty-eight hours “in defense of the Reich.” It helped to have connections. Bruno Lohse managed to find a safe job for a time in one of Goering’s Berlin regiments, and later at the ERR repository in Neuschwanstein. After the Allied drive had been halted in Holland, von Behr too was given a new assignment by Alfred Rosenberg: to transfer all

remaining M-Aktion objects and any other “valuables safeguarded by the ERR” in Holland back to the Reich.

36

The subsequent Battle of the Bulge did not slow him down. On January 15, 1945, with the German armies in retreat from the Ardennes, von Behr and Utikal were still discussing the possibility of relieving the Gauleiter of Westphalia of responsibility for the evacuation from Arnhem of confiscated books of interest to the ERR.

37

It was not until Allied armies actually crossed into Germany that von Behr retreated with his wife to his family schloss. Other staff members distributed themselves among the various ERR depots in Germany.

Dr. von Tieschowitz, thinking already of a very different future, sent as many Kunstschutz records as possible to his former chief, Metternich, in Bonn so that he could put them in safety in “our Rhineland depots.”

38

Similar calculations and struggles of conscience were taking place all over Paris, as they had in Italy, and indeed the very existence of the city now depended on the honor of one man.

A less likely rebel than the stiff and stocky little Prussian, booted and spurred and covered with medals, immortalized in contemporary photographs, can hardly be imagined. But General Dietrich von Choltitz, the brand-new commandant of Paris, as all the world now knows, after a career of total loyalty, chose not to carry out the repeated orders of his commander in chief to do to Paris what had been done to Warsaw only weeks before. This had not been easy. Teams of engineers and demolition experts had been sent by other agencies to mine the Seine bridges. Infantry and Luftwaffe units had been ordered to prepare for house-to-house fighting and bombing which would convert Paris to “a field of ruins.” The Grand Palais was blown up two days before the Allies arrived. Explosives were placed in Notre Dame, the Madeleine, the Invalides, the Luxembourg, and even Hitler’s favorite, the Opéra.

Bombarded by orders for annihilation from Hitler, von Choltitz, without actually disobeying an order, procrastinated and even managed to talk the SS out of taking the Bayeux tapestry off to the Fatherland. The General had help from many quarters. At the Sénat, mines were placed in the basements and the gardens. The caretaker reported all to the préfet de la Seine. When this had no effect he turned to the workers in the power company, and the Sénat was soon stricken with a series of inexplicable blackouts during which workmen managed to disconnect the detonators.

39

The strain became unbearable as the Allies, slowed by disagreements in their councils over whether or not to occupy Paris, hesitated a few miles outside town. But when von Choltitz surrendered on the afternoon of August 25, all the bridges and monuments were intact.

The Louvre and the Jeu de Paume were in the heart of the uprisings

which began nearly a week before Paris was liberated. Impatient staff had to be prevented by Jaujard from prematurely raising the French flag over the museum. All curators were told to stay at their posts and refrain from joining the rebellious crowds in the streets. Arriving at the Jeu de Paume, Rose Valland found that the building had been made part of the German defenses in the Tuileries, which were crisscrossed now with trenches. In the night the terraces had been festooned with barbed-wire barriers. Although the galleries had been cleared, the basements contained large numbers of contemporary works by non-French artists. In the fighting around the German headquarters a few days later, 9 German soldiers would die defending the little museum; 350 more surrendered and were taken to a prisoner-of-war cage set up in the Cour Carrée of the Louvre. Liberators and crowds swarmed over the Jeu de Paume. Mlle Valland, trying to keep them out of the basements, was suspected of collaboration, and forced to open the storage areas, a machine gun held to her back. Luckily for her, no German had sought refuge there, and she soon persuaded her compatriots to leave the building.

In the main complex of the Louvre, where anxious guards patrolled the ancient roofs, ready to put out fires, and all available curators were assigned day and night posts in the vast galleries below, nothing was damaged. But Jaujard, Aubert, and several others were, like Rose Valland, summarily taken prisoner by the Free French troops. While they were extricating themselves, the POWs in the Cour Carrée panicked. Breaking the windows of the museum, they scattered and hid in Egyptian sarcophagi, behind statues, and in all the myriad corners of the building. It took hours to find them all. That evening there was a final German air raid. Then it was over. Paris was free.

40

On either side of the City of Light the Allied armies swept on toward Alsace and up to Antwerp and Ghent, over to Luxembourg and into Holland. They were stopped short of Bruges. In late September they reached Arnhem in the west of Holland. The approach of the front caused a now familiar reaction in Belgium. The principal repository for the Belgian collections was the ancient moated castle of Lavaux St. Anne, located about fifteen miles south of Dinant near the French border. Evacuation back to Brussels had begun in July. In mid-August came reports that the château was being attacked by a strange group of armed civilians suspected to be Germans. The architect Max Winders, in charge of Belgian repositories, managed to rush gendarmes to the scene and the marauders withdrew. The convoys continued. The last one, crawling in close formation down the narrow road along the Meuse at Dinant, was attacked by Allied

dive bombers. Three gendarmes were killed, but Dr. Winders commandeered other trucks and went on, and the paintings survived with little damage.

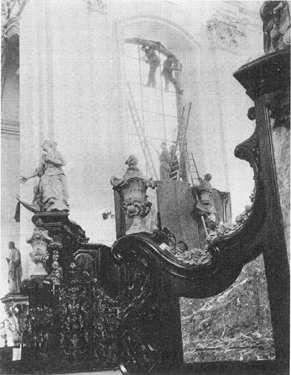

Belgium: Monuments officer Daniel Kern advising on repairs in Namur

Other people in Belgium had ideas about moving things too. Museum officials in Bruges, who had kept many of their greatest works in the town under German supervision, managed to smuggle nine of their most precious pictures out under the noses of the German guards. The cases, which included two of the greatest masterpieces of the Western world, Memling’s

Shrine of St. Ursula

and van Eyck’s

Holy Virgin with Canon van der Paele

, were not missed from the stacks filling the repository. They were secretly taken to the vaults of the Société Nationale in Brussels—which may have been the cleverest move of the war, for the chief of the Kunstschutz in Belgium, Dr. Rosemann, now felt the urge to “safeguard” too.

Other books

The Wrong Woman by Stewart, Charles D

My One Regret (Martin Family Book 3) by St. James, Brooke

Safe Passage by Ellyn Bache

Wet Part 3 by Rivera, S Jackson

Death in Ecstasy by Ngaio Marsh

9781631053580BlackjackHolt by Desiree Holt

Every Night I Dream of Hell by Mackay, Malcolm

Heartless by Catou Martine

The Last Tsar by Edvard Radzinsky

Beer in the Snooker Club by Waguih Ghali