The Parthenon Enigma (62 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The ruin of one person’s house is of less consequence and brings less grief than that of the whole city.

I hate women who choose life for their children rather than the common good, or urge cowardice.

Is it not better that the whole be saved by one of us doing our part?

Not for one life will I refuse to save our city.

Euripides,

Erechtheus

F 360.10–50 Kannicht = Lykourgos,

Against Leokrates

100

93

At the very heart of Athenian democracy, then, lies the conviction that no single life, even a royal one, should be set above the lives of the

many. In the first century, John’s Gospel will define the zenith of love this way: “Greater love has no one than this, that he lay down his life for his friends” (15:13). That this notion of self-sacrifice as love, which sounds to us so familiar, should have been subscribed to at Athens 450 years before Christ is hugely significant, revealing how a trust in one’s fellow citizens allowed rule by the people to endure, even through crises such as only the most authoritarian state could have otherwise survived.

Democracy in its various forms has ever since remained, at bottom, a balance between the individual’s obligations to the community and the community’s responsibilities toward the individual. The latter, though less celebrated, was not ignored at Athens. For two hundred years, the radical Athenian experiment was sustained in no small part by voluntary contributions made by well-off citizens to support those who had nothing.

94

At the same time, an ethos of self-restraint and respect for the law, and, above all, genuine concern for other Athenians—high or low, they were descended from the same exalted stock—ensured the balance. In this way, the fabric of society was as well considered as the peplos of the goddess. Ironically, it is the management of this balance, the quintessential Athenian value, that has most severely challenged contemporary democracies, the would-be heirs of Athens, in our time.

EPILOGUE

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought

,

With many recognitions dim and faint

,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity

,

The picture of the mind revives again.

—

WORDSWORTH

, “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour,” July 13, 1798

TO REVISIT MONUMENTS

in our memories, experiencing them across occasions within the times of our lives, is to revive the “picture of the mind,” as Wordsworth put it. It is difficult enough, conjuring up what we have once seen with our own eyes and how we saw it. How much more difficult it is to look back at antiquity, through the veils and filters that separate us from it. Whether our understanding of the ancient past bears any resemblance to the experience of those who lived in it remains an open question.

In these pages we have had occasion to consider some individual encounters with our subject from across the ages:

Sokrates, whom

Plato’s dialogue places on the banks of the Ilissos; Pausanias’s tour of the Sacred Rock; Cyriacos’s highly original drawings of the Parthenon’s façade;

Evliya Çelebi’s fantastical account of its menagerie of sculptured figures;

Francis Vernon’s meticulous measuring of the temple; Lawrence

Alma-Tadema’s innovative rendering of the frieze in color; Eugene Andrews’s acrobatic and painstaking efforts to obtain squeezes of the Parthenon Inscription;

Isadora Duncan’s ecstatic dance within its colonnade. To these, let us add one more:

Virginia Woolf, who had two encounters, the first on her 1906 tour, the second in 1932. On the latter trip, she wrote:

What can I say about the Parthenon—that my own ghost met me, the girl of 23, with all her life to come: that; & then, this is more compact & splendid & robust than I remembered. The yellow pillars—how shall I say? gathered, grouped, radiating there on the rock, against the most violent sky … The Temple like a ship, so vibrant, taut, sailing, though still all these ages. It is larger than I remembered, & better held together … Now I’m 50 … now I’m grey haired & well through with life I suppose I like the vital, the flourish in the face of

death.

The Diary of Virginia Woolf

, April 21, 1932

1

It may seem strange that the Parthenon should have appeared larger the second time, where most things, particularly those seen in youth, tend to appear shrunken on revisiting. The Parthenon was, in fact, physically larger when Woolf viewed it for the second time, thanks to reconstruction work undertaken by a civil engineer named

Nikolaos Balanos from 1922 to 1933.

2

Balanos’s

restoration of the temple’s north and south peristyles, its southeast cornice and west façade, complete with a new lintel of reinforced concrete, radically altered the monument’s visual impact. The raising of the north and south colonnades reunited the east and west ends of the Parthenon for the first time since its devastation by Venetian cannon fire in 1687. This, surely, accounts for Woolf’s impression that the temple had got larger. Still, she was acutely aware that her age and the approach of mortality had also altered her perception of the building. Time so alters our experience of the visual that no two viewings are ever quite the same.

And so, as each generation visits, and revisits, the Parthenon, the monument is apprehended differently, based on the contexts in which viewers have lived and the cultures that have informed the ways they see and think.

3

Many of us today share something of Woolf’s experience, having seen one Parthenon in our youth and another one “better held together” in our adult years. The past thirty years of conservation work

on the Athenian Acropolis have given us a stronger and more accurately restored Parthenon. The lion’s share of this effort has been devoted to reversing the “improvements” of Balanos, those very interventions that made Woolf’s “second” Parthenon appear sturdier. Balanos’s extensive use of mild steel clamps and ties to connect the crumbling blocks unwittingly caused further damage to a building that had already suffered fire, explosion, weathering, and wear. He neglected to cover his steel reinforcements in lead, as the ancient Greeks had been careful to do with the original wrought-iron clamps that fastened the blocks together. This oversight made the marble all the more vulnerable to the elements. Unprotected steel inevitably rusts and, with this, it expands, leading catastrophically to further splitting and deterioration of the stone.

In 1971, the

Greek Ministry of Culture called for the creation of a task force to address these issues, establishing the

Working Group for the Preservation of the Acropolis Monuments. Five years later, this evolved into the

Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments, a group still in place to this day.

4

Among the many interventions undertaken by the

Acropolis Restoration Service since 1986 is the removal of Balanos’s steel clamps, now replaced with corrosion-proof titanium rods and ties. Each block of the Parthenon has undergone meticulous autopsy, having been cleaned, scanned, and photographed from every angle and, where necessary, restored with infilling of freshly cut

Pentelic marble and white portland cement. Errors in earlier reconstructions have been corrected, blocks have been put back in their original positions, and newly hewn stones have been introduced where structurally necessary (facing page).

5

For the first time in centuries, we now see a more robust and authentic Parthenon, truer to its original construction and, yes, “larger…& better held together.”

This process of taking down the Parthenon and putting it back up, block by block, has revealed a wealth of new information about the materials, tools, techniques, and engineering that went into its original construction.

Manolis Korres (

this page

), head of the

Parthenon Restoration Project for three decades and a member of the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments, has opened for us a whole new understanding of just how the Parthenon was built. He has explained the methods for quarrying and conveying marble blocks down the slopes of Mount

Pentelikon to Athens, the process known as the

lithagogia

, or “stone transporting.”

6

He has identified changes in plan and decoration made during the building’s construction as well as the fact that the Parthenon’s Ionic frieze originally wrapped all the way around its eastern porch. He has reconstructed the original appearance of the building’s roof and walls, including the two windows that flanked its entrance on the east. He has identified the fire damage from Roman times and the traces of the Parthenon’s transformations into church, cathedral, and mosque during the Byzantine, Frankish, and Ottoman periods. Korres has even been able to map the trajectory of the cannon fire of 1687 that blew apart the insides of the Parthenon, documenting the effects of this blast on individual blocks of marble.

7

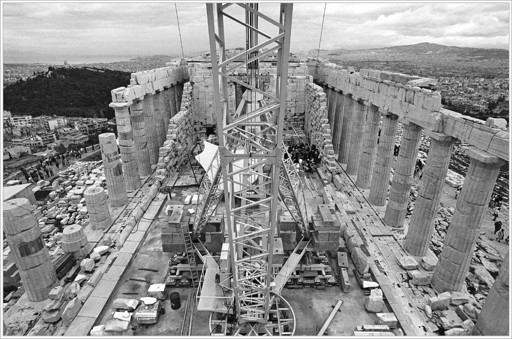

Parthenon during reconstruction work, from east, 1987. (illustration credit

ill.122

)

What emerges is a whole new way of seeing and understanding the Parthenon across the centuries. The new

Acropolis Museum, opened in June 2009, displays for the first time a wealth of contextual material excavated from atop the Acropolis as well as from the wells, tombs, shrines, houses, and foundries sited down its slopes. The museum presents the materiality of the Acropolis from the Neolithic period through late antiquity, giving in-depth, up-close access to objects and images, grand and everyday, sacred and utilitarian, familiar and foreign to us.

8

In so many ways, we stand at a new beginning in Acropolis studies, one in which we can take a fresh look at expertly conserved objects, displayed in spacious, light-drenched galleries that enable us to see with new eyes. It is a moment for looking forward as well as for reassessing that which we believed in the past.

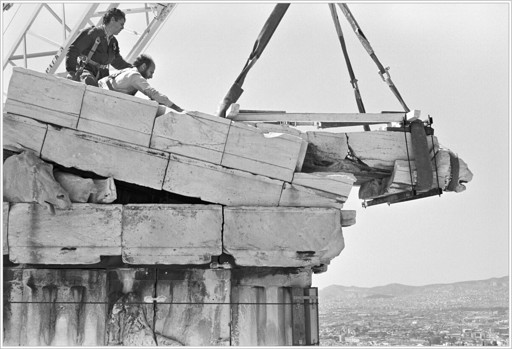

Manolis Korres atop the northeast cornice of the Parthenon, 1986. (illustration credit

ill.123

)

This new context and the fuller picture it gives us of the ancient reality also make it possible as never before to challenge even the most fundamental orthodoxies of interpretation. The accidents of survival in the evidence that comes down to us, the ways in which the “winners” shape the lasting story we receive (regardless of whether it was ever true), the biases of time and culture that heighten and obscure what we regard as vital, the power of personal and cultural

memory in shading our comprehension of the “facts”—all these elements conspire to render our constructions of the past at best spectral and approximate. When the object of scrutiny is as beautiful and iconic as the Parthenon, a monument onto which meanings have been projected across two millennia, it is all the more difficult to see it with “ancient eyes.”

THE TENACITY OF

the received wisdom has been especially true respecting the Parthenon frieze, entrenching an interpretation first

offered nearly 230 years ago. But thanks to more than three decades of work by the

Acropolis Restoration Service, the time is ripe for the re- assessment of old views that have evolved into dogma.

Why has the meaning of the Parthenon frieze been obscured for so long? First and foremost we can cite the shortcomings of the available source material that represents just a fraction of what originally existed.

9

To this, we can add the influence of cultural sensibilities that have rendered the theme of

virgin sacrifice unbearable to imagine on a building regarded as the “icon of Western art,” the embodiment of democracy itself. Post-antique societies have been repelled by the idea of

human sacrifice. Indeed, all major contemporary world

religions place prohibitions on its practice. Relegated to the realm of the barbaric, uncivilized, and “primitive,” it is a practice long regarded as something others do, particularly others who are the enemy. Yet vestigial evidence for human sacrifice can be found in the prehistory of every land on earth. Myth, folklore, and archaeological evidence attest to the practice of human sacrifice in prehistoric Europe, Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific Islands.

10

Indeed, we find reference to it in our oldest surviving religious texts, including the Indian

Vedas.

11