The Parthenon Enigma (60 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Rushing Athena, with Gorgon’s head on her chest. Akroterion figure, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.117

)

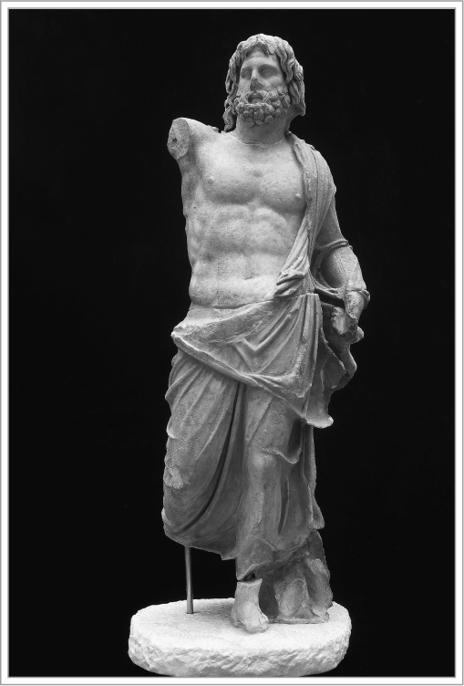

Poseidon emerges from the sea. Akroterion figure, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.118

)

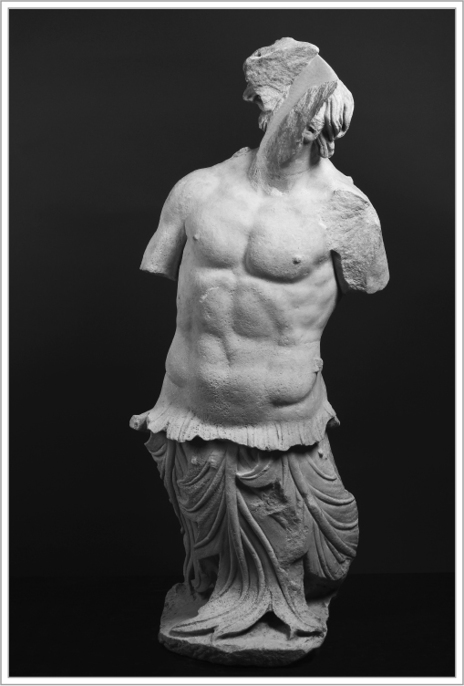

Burly Triton with “skirt” of seaweed. Akroterion figure, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.119

)

WITH SO MANY

direct quotations from the Parthenon manifest, it should come as no surprise that the altar’s Telephos frieze takes direct inspiration from the

Erechtheus frieze of the Parthenon. Indeed, there may be no greater proof that the Parthenon frieze shows the myth of Erechtheus than this later frieze that strives so explicitly to emulate it. Both friezes channel the myth of the city founders, the oracles that determined their fates, their roles in defending their cities from hostile invaders, and their contribution in establishing local cult. Both do so in a long, continuously sculptured “ribbon” of marble relief. But as with the altar’s Gigantomachy panels, there is a key difference. While the Parthenon frieze rings the upper recesses of the peristyle, the Telephos frieze encircles the interior colonnade of the altar’s raised court, seen directly at eye level (

this page

).

70

One wonders if, once again, in their conscientious imitation of the Parthenon, the sculptors at Pergamon set

out to compensate for a weaker claim to divine descent. No one in Athens was in any doubt of Athenian

genealogy. But the Telephos frieze had to make a somewhat harder sell, establishing the legitimacy of the Attalid dynasty for all, Pergamene and visitor alike, to see. There were no centuries of certainty that this descent issued from prehistory.

It is perhaps not surprising that the Pergamene kings, in their sedulous cultivation of neo-Athenian identity, chose for their founder a hero who had been celebrated in an eponymous play of Euripides’s. After all, if the Athenians could point to the master’s

Erechtheus

, the Attalids could claim his

Telephos

.

71

Greek tragedy, just like Greek architectural sculpture, was an important vehicle for retelling charter myths.

72

Again and again in Greek drama we find the foundation of local cult occasioned by the death of a local royal hero: Pentheus at Thebes, Hippolytos at Troezen, Opheltes at Nemea, Iphigeneia at Aulis, Erechtheus and his daughters at Athens, and, yes, Telephos in Mysia. No one was keener to tell these tales than Euripides, whose corpus included not only the

Erechtheus

and the

Ion

, but the

Children of Herakles

and

Iphigeneia at Aulis

, as we have seen, also the

Bacchai

,

Hypsipyle

, and

Telephos

. In fact, the theatrical propagation of myth might have, if anything, seemed more urgent to the Pergamenes.

Andreas Scholl has stressed the architectural similarity between the Great Altar and the

skene

(scene building) of the Greek theater.

73

It is possible that the very form of the altar itself refers to the Greek stage and to the mythic dramas played out upon it.

Presenting a continuous narrative in which leading characters appear repeatedly as they make their way through sequential episodes of the foundation story, the Telephos frieze is nothing if not far easier to read than the one on the Parthenon. We take it in like a cartoon strip with successive events in sequence side by side, beginning with the birth

of Telephos and ending with his death. Thus, we learn the full story of how Pergamon came to be. It begins with the lovely

Auge, princess of Tegea in the Greek Peloponnese, who served as virgin priestess for the local cult of Athena. Her father, King

Aleos, had good reason to place his daughter in this sacred office: an oracle had prophesied that if Auge ever gave birth to a son, he would grow up to kill his grandfather’s male heirs.

Auge had a special role among the

plyntrides

at Tegea, that is, the sacred washers of the goddess’s robes. In this, she mirrors Aglauros, princess daughter of King Kekrops at Athens, who served among the

plyntrides

of Athena. One day, when Auge was on the banks of a stream washing the robes of the goddess,

Herakles came by. He seduced the princess, and as always happens when gods or demigods make love to mortals, Auge immediately conceived. Ashamed of losing her virtue, the princess exposed her infant son on the slopes of Mount Parthenion, meaning “of the virgin.” In this, we see a parallel to King Erechtheus’s daughter

Kreousa, who left her baby son, Ion, to die in a cave on the

north slope of the Acropolis, the very cave in which Apollo had made love to her.

Telephos is saved from exposure by a deer or lioness. Ion is rescued by

Hermes, sent by Apollo to carry him to Delphi. And so did Ion go on to found the Ionian race. Telephos naturally has the chance to father a people, too. As the frieze would have it, these are the

Attalids of Pergamon. Of all the heroes the Pergamenes might have appropriated as their founder, and there are many, they chose thoughtfully and well. Telephos (“the Wanderer”) embodied both their Asiatic roots and their Athenian ambitions.

The north side of the Telephos frieze depicts the earliest chapters in the hero’s life: the story of his parents, their impromptu romance, and its aftermath. Having left baby Telephos on the mountainside, Auge is

sent off to sea in a little boat by her father, to hide her shame from the people of Tegea. The boat washes up at Mysia on the western shores of Anatolia, not far from where the city of Pergamon will be founded. The kindly king

Teuthras rushes down to the beach and rescues Auge, whom he adopts and comes to love as his own daughter. She establishes a cult of Athena, brought directly from Tegea, where she had formerly been priestess of the goddess. The new cult, however, is named for Athena Polias, the same title under which Athena was worshipped at Athens. And as first priestess of Athena Polias at Pergamon, Auge assumes a role parallel to that of the Athenian queen

Praxithea.

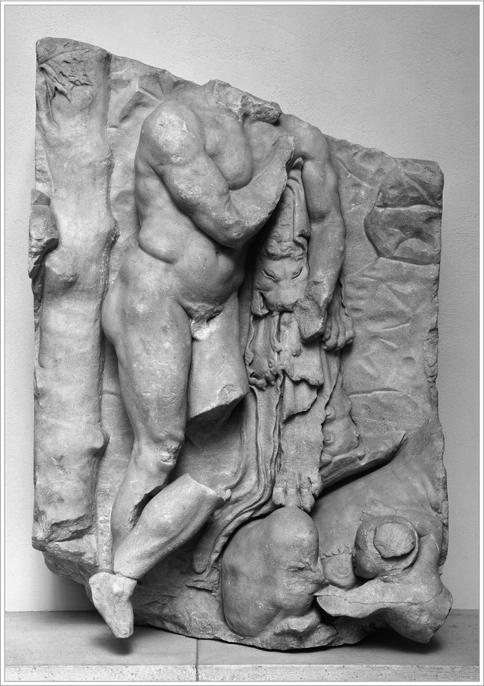

Herakles pauses to admire his infant son Telephos, suckled by a lioness. Telephos frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.120

)

Meanwhile, back on Mount Parthenion, the infant Telephos has survived, nursed by a lioness. On the north wall of the colonnade, we see a panel showing Herakles as he discovers Telephos (facing page).

74

The beefy hero, leaning on his signature club, dissolves into tenderness at the sight of his infant son. The trophy of his violent slaying of the Nemean lion, the fearsome skin he wears, looks more like a benign blanket draped atop his club. With one leg crossed over the other as he watches his boy suckling on the teats of the lioness, the hero seems quite undone. (Earliest traditions had it that Telephos was suckled by a deer rather than by a lioness. But since the deer was sacred to the Gauls, hated enemies of the Attalids, the lioness variant was preferred. Of course, the lion also has the advantage of close association with Herakles’s first labor.)

Along the eastern wall of the colonnade, we see the wanderings of Telephos as a young man. Having consulted the Delphic oracle about finding his mother, Telephos is told to travel east to the shores of Anatolia. This brings him to Mysia, where he is welcomed by the sympathetic king Teuthras, still on his throne. The king begs the obviously heroic lad to help him defeat

Idas, an enemy who threatens to usurp him. Success, Teuthras promises, will win Telephos the hand of Princess Auge in marriage. Since Auge’s priesthood of Athena Polias was no doubt like the sacred office at Athens (on which it is modeled), open to married women, it posed no impediment for her proposed nuptials.

75

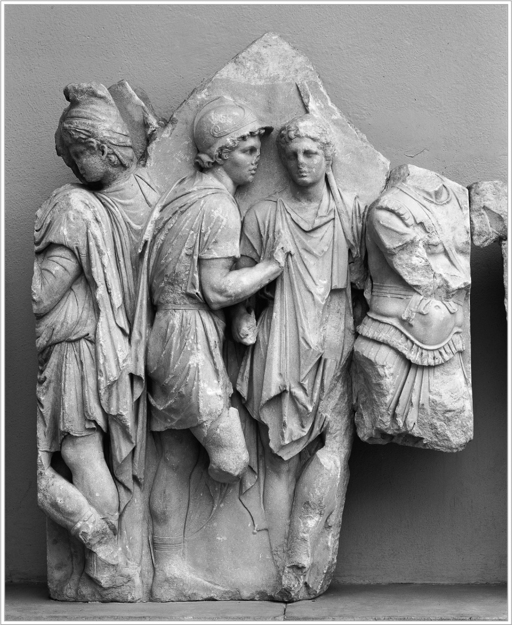

In the panel showing Telephos and his men welcomed at Teuthras’s court, we see figures in Phrygian caps, setting the scene in Anatolia. Next come Telephos’s comrades, one of whom wears an Athenian helmet, signaling that he hails from the Greek mainland. At the far right, we see Telephos himself, in a full-muscle cuirass (following page). The hero turns to the right to receive a helmet and weapons from Auge, again connecting her with Aglauros, for, as we have seen, it is within the sanctuary of Aglauros on the Acropolis’s east slope that Athenian ephebes received their weapons. At Athens, it was the priestess of Aglauros who oversaw the ritual in which young soldiers also swore their oath of loyalty. And here, we find Auge enacting this same priestly role.

Telephos as a young warrior wearing breastplate (far right) welcomed in Mysia; his comrades (at left) wear Phrygian cap and Attic helmet. Telephos frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.121

)

The remainder of the east frieze is devoted to Telephos in battle with Idas’s troops and the aftermath. Returning as a victor, Telephos is met by King Teuthras, ready to make good on his promise of marriage. Fortunately, mother and son recognize each other just in the nick of time, averting an incestuous side story. But Telephos does not remain lonely, going on to marry the local Amazon queen,

Hiera. When Argive Greeks arrive in Mysia, having lost their way to the

Trojan War, they engage in battle with Hiera’s Amazons. The frieze shows Telephos fighting for the Amazons against the Greeks. Thus are the Attalids ingeniously able to

write their founding hero into the scripts of two great boundary events we have already seen in the Parthenon metopes: the Trojan War and the Amazonomachy. In the Pergamene version of the battle with the Amazons,

Hiera is killed, and Telephos is badly wounded by

Achilles.

Not without justification, it happens.

Dionysos had been deeply offended when Telephos failed to make sacrifice to him. The god retaliated during the battle with the Greeks, causing Telephos’s leg to become entangled in the roots of a grapevine, making Telephos a sitting duck for Achilles’s lance. The son of Peleus wields the special spear the Centaur Chiron had given his father as a wedding gift. The wound Achilles inflicts will not heal, and Telephos is lamed.