The Parthenon Enigma (57 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

So it was that Duveen’s money bought him a front-row seat at the super-cleaning of the Elgin Marbles from June 1937 through September 1938. Lord Duveen, as he was known by now, enjoyed very special access to the sculptures and the team of unskilled masons charged with scrubbing them; indeed, he gave orders directly to the crew.

29

They had wire brushes, an ample supply of the harsh abrasive Carborundum (silicon carbide), and, for particularly stubborn stains, copper chisels.

30

On September 26, 1938, the scientist

H. J. Plenderleith reported that the scraping of the sculptures had exposed the light crystalline subsurface of the marble to a raw state. In some places, the stone’s original surface had been stripped of one-tenth of an inch. Consequently, certain figures appeared to have been “skinned.”

31

Sculptures particularly affected included, from the east pediment, the figure of

Helios, the back of the two horse heads from his chariot group, and the head of the horse pulling Selene’s chariot. From the west pediment, it was the figure of

Iris that suffered.

32

The trustees decided not to make a public statement about what had happened; nonetheless, news of the cleaning was leaked to the press, and on March 25, 1939, the

Daily Mail

broke a sensational story: “Elgin Marbles Damaged in Cleaning … Traces of patina have been removed leaving an unnatural whiteness.”

33

As tantalizing as the story was, it was soon wiped off the front pages with the onset of

World War II; indeed, the Elgin Marbles would be kept under wraps for the duration of the war and the frieze transferred to an unused section of the London Underground for safekeeping. This was a wise move, for the

Duveen Gallery was badly damaged in the bombings of 1940 and had to be entirely rebuilt. It did not open again until 1949, by which time the wire brush scandal had been largely forgotten and remained so until the publication of the third edition of

William St. Clair’s

Lord Elgin and the Marbles

in 1998. Controversy was reignited. In response, the British Museum produced an unprecedented and wonderfully comprehensive publication of all internal documents relating to the case. In addition, it sponsored an international conference on the matter in December 1999.

34

Thus, much of what we know about the long debate over polychromy, as well as the British Museum’s stewardship of the marbles, has come to light only recently.

We have also learned much from the ongoing autopsy of the Parthenon itself. Indeed, exciting new evidence for the vivid painting of the temple has been revealed by the

Acropolis Restoration Service’s work on the Parthenon’s west colonnade. It was a matter of removing other architectural accretions. During the Frankish period, a bell tower with staircase was built within the porch at the very southwest corner of the Parthenon, then serving as the cathedral

Notre-Dame d’Athènes. One of the tower’s brick walls had long concealed a section of an anta capital, just beneath the architrave. With the Ottoman capture of Athens in 1458, the cathedral was transformed into a mosque and the bell tower into a minaret.

In the early 1990s, the brick wall of this medieval staircase was removed. For the first time in 750 years, the anta capital of the Parthenon’s rear porch was exposed. Extensive traces of green and red paint were found preserved on its

Ionic and Lesbian moldings, as well as on the profile moldings above the frieze within the north and west colonnades.

35

Separately, Egyptian blue and red hematite paint have been found on the horizontal cornice as well as on the triglyph-metope frieze.

36

Laser surface cleaning, undertaken in 2006–2009,

37

has further revealed traces of light green paint on the costumes of two of the

horsemen on the west frieze, the only stretch of the relief panels that Elgin left in place.

38

And, on the west pediment, significant traces of blue (amid an orange-brown layer of the original ancient patina) have been revealed on the drapery stretching across the back of King Kekrops (

this page

).

39

The polychromy wars entered a twenty-first-century phase with the opening of the new

Acropolis Museum on June 19, 2009. Timed to co- incide

with the festive inauguration of the galleries in Athens, there came from the British Museum a press release announcing new research that revealed polychrome paint on the Elgin Marbles. Using the latest technology to detect infrared light emitted by pigment particles of Egyptian blue, a British team had been able to recover barely visible traces of color on the belt of Iris from the west pediment. “I always believed the frieze must have been painted,” offered one senior curator. “This new method leaves no room for doubt.” He further observed that originally the marbles would have been painted red, white, and blue. “Yes,” he added, “the colours of the Union Jack,” shooting a little cannonball of British nationalism toward the happy party gathered at the foot of the Acropolis.

40

THE POLYCHROMY CONTROVERSIES ARE

but a short chapter in the long, vexed history of efforts to see the Parthenon and the people who made it as they were. It is a chapter, nonetheless, typical of the perils of self-projection in attempting to apprehend the distant past. Athens having served as an ideal for so many later cultures, it is perhaps unavoidable that of all antique realities it would have suffered the most distortions in the course of successive attempts at appropriating its legacy. Only recently have some advanced methods of investigation liberated our own understanding from preconceptions that have stood since the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. And yet there remains who knows how much more to unearth.

At the same time, popular understanding, particularly as reflected in our civic discourse and architecture, continues to uphold certain assumptions of supposedly Athenian derivation—assumptions, for instance, about the primacy of empirical reason over belief, the centrality of the individual, and the basis of democracy—just as surely as it clings to an aesthetic of pure-white marble. As a practical matter, we are bound to stick to our self-serving construction of the Athenian reality for the foreseeable future. It may, therefore, come as some comfort to discover that peoples more historically proximate to classical Athens, with the sincerest of intentions and the most studious of efforts, were not altogether unerring in their effort to capture the Athenian ideal, to develop from it an identity of their own. To set things in perspective,

then, perhaps even to gather a thing or two we latter-day imitators might have missed, let us in closing consider the case of the very first would-be Athenians.

AS EARLY AS

the late fourth century

B.C.

, the political and economic hegemony of Periklean Athens was mostly a

memory. At the beginning of the second year of the

Peloponnesian War, in 429,

Perikles himself had perished, struck down by the deadly plague that would claim a full third of the Athenian population. Things went from bad to worse, the war ending in defeat for Athens and its allies in 404. The Greeks would continue their infighting until Philip of Macedon finally conquered them in 338, bringing a decisive end to the Athenian democracy.

The Athenian legacy of course lived on in the new regime, not least because of

Aristotle’s conscription as tutor to Alexander, Philip’s son. Still, as the age of the Parthenon receded, the

geopolitical center of the Greek world shifted east. Successive powers would rise, claiming, to one degree or another, identification with bygone Athenian greatness. The first and most zealous of these would be

Pergamon. During the

latter third and entire second centuries

B.C.

, for about 150 years, this kingdom in western Anatolia set about modeling itself in the image of classical Athens. So passionate was the Pergamenes’ love of Athenian art, architecture, philosophy,

religion, and culture that they lavished their own “city on a hill” with gleaming white marble buildings in conscious imitation of the Periklean Acropolis.

41

And though aware that their ancestry sprang from Tios on the Black Sea, the Pergamene kings acquired through pure invention, abetted by the Athenians themselves, an identity that can be called neo-Athenian. This they did even to the point of carving a frieze of their own, in direct imitation of the

Parthenon frieze, linking themselves to the very

genealogy that the Athenians had guarded so jealously and celebrated annually in the

Panathenaia, by this time, for more than four hundred years.

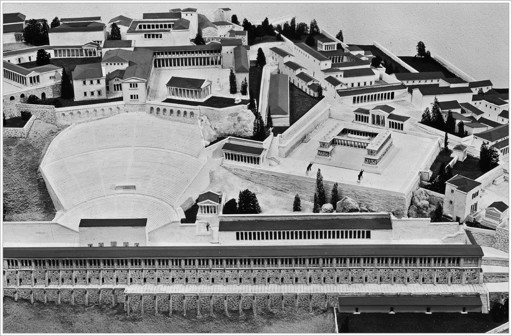

Pergamon acropolis, reconstruction model with theater, temple of Dionysos, and stoa; on summit above, temple of Athena Polias and the Great Altar. (illustration credit

ill.108

)

By the middle of the second century, Pergamene kings could boast of their own acropolis of white marble buildings, including a temple to Athena Polias Nikephoros (“Athena of the City, Bringer of Victory”), a copy of Pheidias’s statue of the Athena Parthenos, and, perhaps also, a copy of Pheidias’s

Bronze Athena,

42

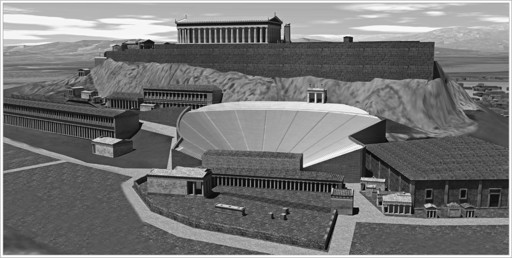

as well as a cavernous theater nestled into the citadel’s precipitous western slope, anchored at its base by the temple of Dionysos and a long, sprawling stoa (facing page).

It was no coincidence, of course, that each of these elements could also be found on the Athenian Acropolis (below). The Pergamene kings were likewise quick to introduce local cults of Athena Polias, Dionysos,

Zeus,

Asklepios, and

Demeter and Kore, replicating the long-established religious institutions as well as the more tangible fixtures at Athens. What motivated these newcomers to emulate so completely and so suddenly the Athenian model?

Hypothetical visualization of Athenian Acropolis, south slope with Theater of Dionysos, temple of Dionysos, Odeion of Perikles, Stoa of Eumenes II; on summit above, the Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.109

)

SET ON A PRECIPITOUS SUMMIT

in northwestern Asia Minor, roughly opposite the Aegean island of Lesbos, Pergamon is an easy 26-kilometer (16-mile) sail up the Kaikos River from the Mediterranean Sea. The city’s commanding cliffs attracted King Lysimachos (360–281

B.C.

) of Thrace and Mysia, who inherited all of western Asia Minor following the death

of Alexander the Great in 323

B.C.

With its natural defenses and proximity to the fertile fields of the Kaikos River valley to feed a large garrison, this was the perfect place to build the royal treasury. To safeguard his wealth, Lysimachos appointed his trusted comrade

Philetairos (ca. 343–263

B.C.

), but following a series of bloody clashes between

Lysimachos, King

Seleukos (another of Alexander’s heirs), and Seleukos’s rivals, Philetairos found himself the last man standing.

43

He kept the treasure and used it to establish his own royal line, one that became known as the Attalids, presumably after his father, who was likely named Attalos.

Philetairos died in 263

B.C.

, succeeded by his adoptive nephew, Eumenes I. This Eumenes declared sovereignty for Pergamon, defeating the Seleucid king, Antiochos, in 262. He also became a great patron of Athenian philosophers, befriending

Arkesilaos, arguably the most influential head of the Academy after the death of

Plato.

44

Thus, the Attalid kings began a long relationship with the philosophical schools of Athens, a fruitful partnership that would bolster their claim to being special caretakers of Athenian learning and culture. Another nephew of Phileteiros’s, Attalos I, succeeded Eumenes upon his death in 241. Like his cousin, Attalos I was well acquainted with philosophical circles in Athens, becoming a close associate of

Lakydes, faithful follower of and successor to Arkesilaos at the Academy. In fact, so great was Attalos’s esteem for his learned teacher that he established a special garden on the Academy grounds, which became known as the Lakydeion.