The Parthenon Enigma (63 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

To recoil at the thought of an act as “barbaric” as human sacrifice displayed above the door of the Parthenon may also be a result of viewing it, mistakenly, in the secularized terms of Western civic life, rather than as a religious building primarily. We might ask, what Christian church does not show a scene of human sacrifice above its door? The crucifixion of Christ, moreover, follows a very familiar pattern: kingly father gives beloved child to save populace.

The ultimate sacrifice, in which a precious child is given for the

common good, is in fact central in many world religions, just as it is in global myth and folklore. In the Hebrew Bible’s

book of Judges we learn that

Jephthah must sacrifice his daughter in fulfillment of a vow he made to God.

12

In the

book of Genesis we find God testing

Abraham’s faith, asking him to sacrifice his beloved son,

Isaac. Abraham obediently leads the boy to the top of Mount Moriah, wholly prepared to kill him. But the willingness is sacrifice enough: stopping the deed just in the nick of time, the Lord says to Abraham, “Now I know that you fear God.”

13

A ram is substituted for Isaac and the burned offering proceeds, following a pattern that is also found in Greek myth. We see, for example, a

deer substituted for Iphigeneia as she is led to sacrifice upon the

altar at Aulis.

14

That classical Athens should have a story of sacrifice,

death, and salvation at the heart of its founding myth makes perfect sense in the context of a long myth tradition of maiden sacrifice in times of crisis. There are other cross-cultural continuities as well. The two eldest daughters of King Erechtheus, shown on the Parthenon’s east frieze, carry their funerary shrouds on stools upon their heads (

this page

). The youngest, with the help of her father, displays the funeral dress that she is about to put on. The central panel thus also follows the formula of sacrificial victims shown carrying the implements of their own sacrifice.

Isaac is regularly portrayed transporting upon his back the wooden sticks with which the altar fire will be lit. In the Gospels, Jesus Christ carries the cross to which he will be nailed. This imagery makes implicit that the victim submits, wittingly or not, to be killed. The daughters of Erechtheus on the Parthenon frieze need not be dragged to the sacrifice required to save their city. Their willingness, in turn, sets the civic example, just as Jesus’s willing death on the cross sets the moral example: “No one has greater love than this.” In this way, the

Athenians made self-sacrifice as essential a part of

to kalliston

and the democratic ideal as the Christian Church made it requisite for entry into the kingdom of heaven. “For whoever would save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16:25).

It should not be forgotten that the Parthenon served as a Christian church for slightly longer than it was a temple

of Athena, at least from the mid-sixth century

A.D.

until the conquest by the

Ottoman Turks in 1458.

15

The long practice of

Christianity within its walls may have erased any

memory of the sacrificial scene carved above the Parthenon’s eastern door. In fact, the sculptured panel showing the family of Erechtheus was taken down to accommodate the apse at the time of the conversion (facing page). The central slab of the east frieze would remain hidden until Elgin’s day, built into an Acropolis fortification wall. Christianity might have pushed back against any remnant of the “pagan” myth of the sacrifice of Erechtheus’s daughters, a distraction from the salvific sacrifice of Christ. We know that the Christians defaced other Parthenon sculptures in an attempt to mitigate their heathen message. On the other hand, they left one

metope, at the very northwest corner of the temple, completely untouched, because it resembled, to their eyes, the angel Gabriel appearing to the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation.

16

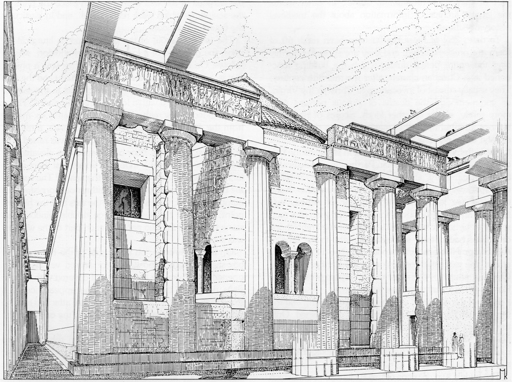

Reconstruction drawing of the Parthenon as church in the twelfth century, showing east end with apse, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.124

)

IN CONCLUDING OUR LOOK AT

the Parthenon, let us consider the question of how, generally, conventional wisdom comes to be established as fact. Indeed, how does “

knowledge” get made? Helpful in this regard is

Joel Mokyr’s important work on the “

knowledge economy,” in which he lays out ways of thinking about resistance to new ideas. Mokyr demonstrates how knowledge is a self-organizing system that can be explained in Darwinian terms. Like genes, ideas are subject to a kind of natural selection. Unless innovations are advantageous, knowledge systems resist change and favor self-replication, rejecting novelty and deviations from accepted norms. Thus, contradictory knowledge has few “reproductive opportunities.”

17

“In the evolution of useful knowledge,” Mokyr writes, “resistance to novelty comes from the preconceptions of existing practitioners who have been trained to believe in certain conceptions they regard … as axiomatic.”

18

Mokyr cites a number of famous examples: Tycho Brahe’s denial of the Copernican system, Einstein’s resistance to quantum theory, Priestley’s refusal to give up belief in phlogiston, von Liebig’s denial of Pasteur’s proof that fermentation was a biological and not a chemical process. Despite

Edward Jenner’s discovery, in 1796, of the vaccination reaction, it took another century and the triumph of germ theory for his work to be accepted. Indeed, when he applied to the

Royal Society to announce his findings, Jenner was told not to risk his reputation by presenting anything that appeared so much at variance with established

knowledge.

19

In the case of the

Parthenon frieze, I believe that two developments in the first half of the nineteenth century might, in their own ways, have contributed to the narrowing of debate over how we view its sculptures and the building they were set on. Together these two forces account for much of the tenacity of the conventional wisdom.

A mere two months following the official announcement of the invention of the

daguerreotype photographic process, in October 1839, an Excursion Daguerrienne set out for the Athenian Acropolis. On this

expedition, Pierre G. G. Joly de Lotbinière shot the first

daguerreotype of the Parthenon (

this page

).

20

One cannot imagine how many millions of photographs of the temple have been taken since. Indeed, for most people, the first and only introduction to the monument will be through photographs, film, or digital images.

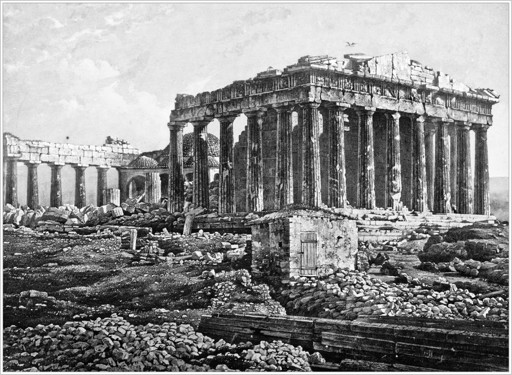

Daguerreotype, P. G. G. Joly de Lotbinière, 1839, in

Excursions daguerriennes

(1841–42). (illustration credit

ill.125

)

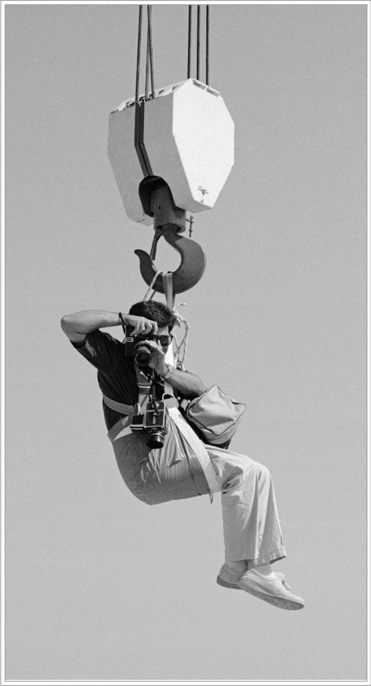

Frédéric Boissonnas photographing the Parthenon, at northwest corner, 1907. (illustration credit

ill.126

)

Socratis Mavrommatis photographing the Parthenon, 1988. (illustration credit

ill.127

)

Over the next century and a half, photographers flocked to the Acropolis, striving ever harder to capture the Parthenon’s vaunted magnificence. There were no lengths to which they would not go, however precarious, to get the perfect shot. From Frédéric Boissonnas’s extraordinary series of images taken in the first decade of the twentieth century (previous page, top) to Socratis Mavrommatis’s expert documentation of the Acropolis restoration over the past thirty years (previous page, bottom), the reproduction of the Parthenon through photography has made the image impenetrably iconic.

21

It became, as it would remain, whatever these countless images seemed to suggest. That it might not correspond to an understanding reinforced by that endless reproduction would be akin to suggesting that the

Mona Lisa

is not actually smiling.

One can hardly escape our modern notions of what visual images are for: documenting the present or

what is

. But revisionist work on the function of images in Greek antiquity has stressed a rather different role: to enable viewers to see what was

no longer

visible, that is, the mythical days of the legendary past.

22

There was no need for images of what could be seen by the human eye. Their primary role was, instead, to restore a time and a world that were lost, and thereby to make the past present. Once we engage with this ancient way of thinking, we can appreciate its internal logic. Looking at ancient images not as snapshots of contemporary reality but as windows onto the remote past, we come closer to the experience of how the ancients themselves looked at them. And we see how certain interpretations, however long-standing, become implausible.

The second development of the past two centuries has been the stress placed on the civic and political content of the frieze at the expense of its mytho-religious aspect. The reinforced association of Parthenonian style with our notion of democratic government has been relentless. But the fact that our banks and post offices (and the U.S. Custom House on Wall Street in New York, seen on facing page) may look like Greek temples is no reason to conclude that Greek temples themselves were decorated with secular iconography drawn from the historical present. Nevertheless, the identification of the Parthenon with modern Western

ideals was so intense by the nineteenth century it was impossible for some to resist the impulse to carry away and take possession of the icon, or at least parts of it, which is precisely what happened.

By the time the little mosque was removed from the Parthenon in the 1840s, Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin, in his role as British ambassador to the Ottoman court at Constantinople, had long perpetrated his own, far more notorious removal, managing to cut most of the sculptures from the temple, pack them up, and ship them to England.

23

Whether Elgin secured permission from Sultan Selim III is contested to this day.

24

What is clear is that Elgin took the sculptures at a time when the Greeks were under Turkish occupation and not in control of their country. Whatever favors the sultan may have granted Elgin were given largely because England was the enemy of the Ottomans’ enemy, France.