The Parthenon Enigma (59 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

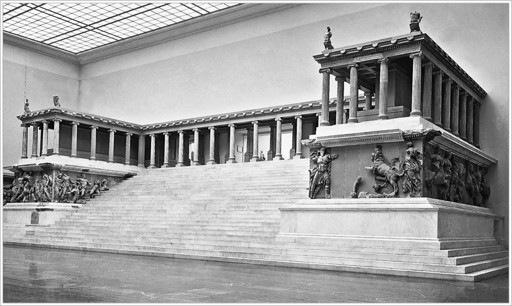

The Great Altar’s sumptuous sculptural program is a tour de force carved in marble. The exterior frieze wraps around the base of the monument, in defiance of all architectural conventions that normally require

such a frieze to be set high above the

Ionic colonnade. Through the radical innovation of bringing the sculptured figures down to ground level, the

altar seems intended to engage human viewers in the energy of its composition. So much for the gods as the only intended viewers; perhaps an acquired legacy was thought to require more on-the-ground selling.

Great Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, with broad western staircase leading up to a raised court; Gigantomachy frieze wraps around exterior beneath colonnade. (illustration credit

ill.111

)

The frieze presents a very ancient narrative, one borrowed straight from Athens: the Gigantomachy, the cosmic conflict presented through a multitude of images capturing the very heat of combat. It is estimated that there were between eighty and a hundred figures in the original composition spread across a field 113 meters (371 feet) long and 2.3 meters (7.5 feet) high. In what survives, we can recognize the full pantheon of divinities listed in Hesiod’s

Theogony

.

65

Gods of the cosmos and the oceans join with the younger generation of Olympians to battle the Titans and the Giants, fantastic creatures depicted with wings, serpent legs, the heads of beasts, and other marks of monstrosity.

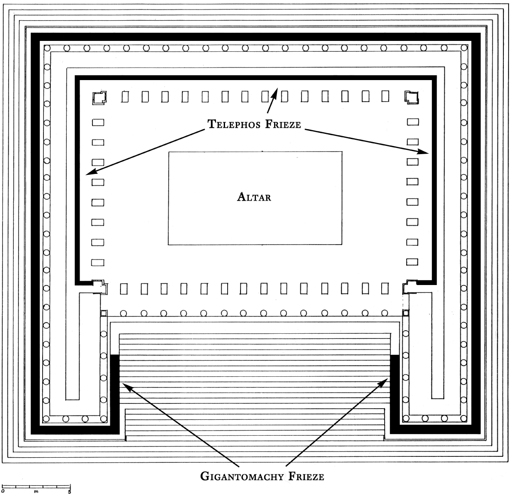

Plan of the Pergamon Altar showing placement of the Gigantomachy frieze (beneath colonnade wrapping around the exterior) and the Telephos frieze (inside the raised court, wrapping around the interior colonnade). (illustration credit

ill.112

)

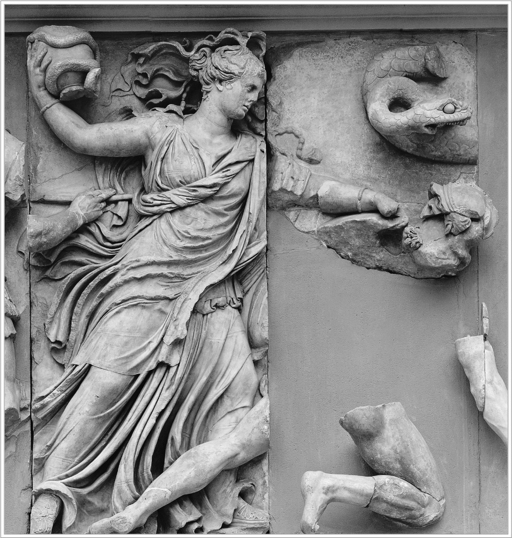

Athena fights winged giant (at left) while Nike crowns her (from right); Ge emerges from the earth, pleading for her son. East frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.113

)

The Giants of the Pergamon Altar can be seen as Hellenistic incarnations of the terrifying creatures that appeared in our discussion of the Archaic Acropolis at Athens (

chapter 2

). Some recall aspects of the hideous Typhon with broad wings and serpent legs. Still others are reminiscent of the fish-tailed Triton that we saw wrestling with Herakles on the poros pediments. The triumph of order over chaos, as represented by the

Olympian gods’ overcoming the Giants, works also as a metaphor for Pergamene victory over the barbaric

Gauls.

At the west side of the altar, a flight of two dozen steps 20 meters (66 feet) wide leads up to an interior court. Here, a second, smaller frieze wraps around its interior colonnade (previous page). Forty-seven of its original seventy-four relief panels survive. They tell the story of the foundation of Pergamon through the exploits of the hero

Telephos, son of Herakles and the princess

Auge of Tegea on the Greek mainland.

66

In contrast to the flamboyant style of the Gigantomachy frieze, this interior frieze presents a quiet, dignified narrative, one that takes us rather literally through the life story of Telephos. The juxtaposition of two very different sculptural styles mirrors what we find on the Parthenon,

where the vibrant poses

of Athena and Poseidon on the Parthenon’s west pediment contrast with the calm, collected mood of the foundation story told on the frieze. Indeed, the

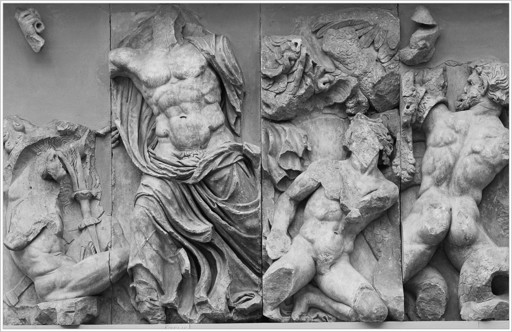

Pergamon Altar is a very studied imitation of the Parthenon in its style, its content, and the programmatic organization of its sculptured decoration. The figures of Athena and Zeus on the east frieze of the Great Altar are directly modeled on the dynamic central composition of Athena and Poseidon on the Parthenon’s west pediment. We see Athena in the same energetic stance, lunging to the right, with her left leg bent at the knee and pushing through the great sweep of her dress (facing page). She grabs a fallen, winged giant (Enkelados?) by the hair while Ge (his mother?) emerges from the earth, imploring Athena to spare him. Meanwhile, Zeus’s explosive pose, with thick, exaggerated musculature, derives directly from the figure of Poseidon on the Parthenon’s west gable (below). He raises his arm to hurl a thunderbolt (in place of Poseidon’s trident) as three Giants are brought to their knees (and snake-legs) before him.

Again and again on the Pergamon Altar, we find references to Athens, its cosmic struggles, and its defining boundary events. At the north side of the Gigantomachy frieze, we see a dynamic female figure poised to hurl a globe encircled with a coiling snake (following page). The maiden pulls her right arm back, fully cocked for the pitch, and thrusts her left arm straight out, to steady her aim. This figure has traditionally been identified as a personification of Nyx, goddess of the night, or, alternatively, as Persephone or Demeter.

67

One cannot help but be reminded, however, of the young Athena, the only deity in Greek myth who is famous for pitching a serpent into the sky. Hurled to the very pole of heaven, Drako’s constellation dominates the northern sky ever after. Can it be a coincidence that this image of a serpent thrown skyward is placed on the north side of the Gigantomachy frieze? Even though this figure is not meant to represent Athena, it is deeply evocative of her vibrant catasterization of that most deadly of Giants.

Zeus hurls thunderbolt at Giants. East frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.114

)

“Nyx” hurls serpent into the heavens. North frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.115

)

Further along the north frieze we find another quotation from Athens, indeed, from the Parthenon sculptures. A monstrous fish, replete with scales, gills, fins, and a bulging eye, emerges spectacularly from the waters beneath

Helios’s chariot (inset, facing page). We think immediately of the Parthenon’s abundance of serpents and fish-tailed creatures, especially the fish that similarly swim beneath Helios’s chariot on east metope 14 (

this page

), just behind the victory monument of Attalos II (

this page

). The Pergamon Altar thus takes familiar land and marine creatures seen on the Athenian Acropolis and inflates them to an all-new level of amplification in the bombastic sculptures of the Gigantomachy frieze. And one only need look to the snake bursting from its relief background and slithering up the altar’s staircase (above) to be reminded of the serpents of the Archaic Acropolis (insert

this page

, top, and

this page

, top). Makes one wonder just how much fishy iconography we have lost from the Acropolis.

68

Serpent slithers up western staircase, locked in combat with eagle of Zeus, while fallen winged giant looks on. Inset: Monstrous fish emerging from the sea beneath Helios’s chariot, north side. Gigantomachy frieze, Pergamon Altar. (illustration credit

ill.116

)

EVEN THE ROOF

of the Pergamon Altar was decorated with marble akroteria figures familiar from the Athenian Acropolis: Athena,

Poseidon, Centaurs, and

Tritons. Once again, the figures of Athena and Po- seidon seem to quote their likenesses on the Parthenon’s west pediment: Athena wears a

Gorgon’s head aegis draped across her chest, as she rushes forward (following page, left); Poseidon turns his full, rippling torso to the viewer as he lifts what is, no doubt, a trident with his outstretched right arm (following page, center). As for the altar’s rooftop statues of rearing Centaurs, can they have been inspired by anything other than the south metopes of the Parthenon? Likewise with the burly Triton akroteria, hulking mermen with seaweed around their waists and fish tails emerging from their loins (above, right).

69

These are the sons of Triton, the same sea monster shown wrestling Herakles on the Bluebeard Temple of the Archaic Acropolis and repeated in the Triton figures of the Parthenon’s west pediment (insert

this page

, right).