The Parthenon Enigma (26 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Professor André Bataille and Mlle Nicole Parichon extracting the

Erechtheus

fragments from the mummy cartonnage.

Life

, November 15, 1963, 65. (illustration credit

ill.40

)

Scholars of Greek comedy were energized. Among them was the young

Colin Austin, a doctoral student at

Christ Church, Oxford, just finishing his dissertation on the comic playwright

Aristophanes. In the autumn of 1966, Austin traveled to Paris. He was welcomed by

Jean Scherer, Bataille’s successor at the

Institut de Papyrologie at the Sorbonne. Scherer presented Austin with fragments of the

Sikyonios

for study, making clear that he had reserved for himself the rights of publication. He also produced additional fragments recovered from mummy casing 24, and considering these mere “scraps” compared with Menander’s text, he generously offered them to the young scholar to publish.

Colin Austin’s heart skipped a beat. In that instant, he had already recognized that these “scraps” contained lines from the long-lost play titled the

Erechtheus

, by one of the greatest of all Greek dramatists, Euripides.

4

The existence of the

Erechtheus

had long been known from later authors who quote from it freely.

5

Far and away the longest quotation is the chunk of fifty-five lines we have seen

Lykourgos use in his oration

Against Leokrates

delivered in 330

B.C.

, nearly a century after the

Erechtheus

was first performed, probably around 422

B.C

.

6

Making his case against the traitor, Lykourgos hails the example of the eponymous king’s daughters, who gave their lives to save Athens, and he quotes the patriotic speech of their mother, Queen

Praxithea, who willingly acceded to sacrificing her progeny. But how does a Hellenistic papyrus text, literally buried until the early twentieth century and still unrecognized for another sixty years, transform our understanding of the world’s most familiar building today? As much as anything, the answer reveals the improbably circuitous workings of the field of classics.

Colin Austin’s

knowledge of Greek was so expert that he instantly recognized in the Sorbonne papyrus the same play of Euripides that Lykourgos had quoted in his oration. To recover a more substantial portion of a major text was a coup that classicists dream of. But Austin kept a poker face. Thanking the professor, he went straight home, over the moon at his good fortune.

Austin dispatched his duties in record time, transcribing the Greek

and publishing it, with commentary, a year later. It was not easy work. To begin with, huge chunks of text were lost where the paper had been cut into the shape of wings, the wings of the Egyptian Horus falcon, a decorative element on the mummy case to which the cartonnage naturally had to conform (below).

7

Austin’s first publication of the fragments appeared in

Recherches de Papyrologie

for 1967, with translation in French, under the title “De nouveaux fragments de l’

Érechthée

d’Euripide.”

8

The following year, he published the Sorbonne papyrus together with all known fragments of the

Erechtheus

from other sources in his

Nova fragmenta Euripidea in papyris reperta

.

9

Austin’s accompanying commentary was in Latin with no translation, in accordance with the convention of the German series (Kleine Texte) in which it appeared.

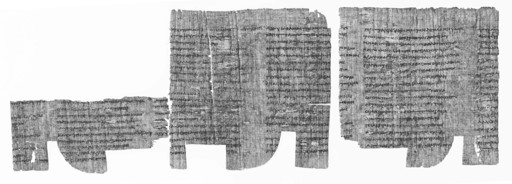

Fragments preserving Euripides’s

Erechtheus

. Sorbonne Papyrus 2328b–d. (illustration credit

ill.41

)

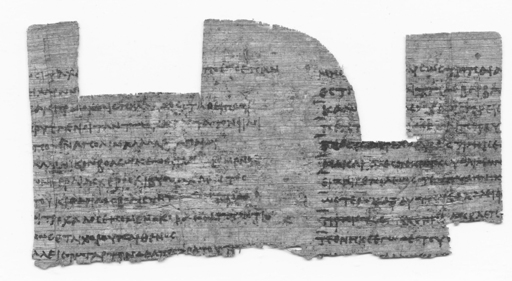

Fragment preserving Euripides’s

Erechtheus

. Sorbonne Papyrus 2328a. (illustration credit

ill.42

)

While the monumental discovery of Euripides’s lost

Erechtheus

was big news in philological circles, it remained largely unnoticed by archaeologists. Such discoveries take quite a while to reach the mainstream of classical studies, let alone the general public. A Spanish translation of the play would appear in 1976 and an Italian one in 1977.

10

But the text would not come out in English until 1995, more than thirty years after the recovery of the fragments.

11

And nearly twenty-five years would pass between Austin’s first publication of the

Erechtheus

fragments and my demonstration of their relevance to the

Parthenon frieze.

12

One might well imagine classical studies as a focused and insular field in which everyone knows the doings of everyone else. But those who study Greek sculpture rarely keep up with papyrological discoveries, just as papyrologists seldom follow what’s new in Greek

architectural sculpture.

The fragments peeled from Jouguet’s mummy casing 24 are known as

Sorbonne Papyrus 2328 and contain approximately 120 lines of the

Erechtheus

, not including the 55 quoted by Lykourgos. Prior to this discovery, only 125 lines of the play had been known: Lykourgos’s quotation plus 34 additional lines given by

Stobaeus and various individual lines quoted in a number of other sources.

13

With the new discovery the extent of the play recovered rose to just under 250 lines, which, to judge by other Euripidean dramas, should account for one-fifth or one-sixth of the entire play.

14

But how do new fragments of this ancient play lead us to reexamine the Parthenon? Before we answer that question in the next chapter, it is worth delving a bit into the story of the primordial Athenian king, who looms larger in the classical Athenian consciousness than has been understood for millennia.

AS WE HAVE SAID

, it was through Lykourgos’s lengthy quotation in

Against Leokrates

that the

Erechtheus

had been known to modern readers. But the play’s significance, and that of its namesake, Erechtheus, had not been fully appreciated until Austin’s publication of the new fragments in 1967. Indeed, Erechtheus had been best known from the temple on the Acropolis that bears his name, the

Erechtheion. Its construction is generally placed in 421

B.C.

, after the

Peace of Nikias brought a break in the fighting between Athens and

Sparta, ending the first phase of the

Peloponnesian War. The Erechtheion is thought to have been completed

sometime after 409/408

B.C.

, when inscribed building accounts detail work completed as well as work left to be done.

15

Largely based on circumstantial evidence, the date for the start of construction on the Erechtheion remains contested, with some scholars putting it as early as 435

B.C

. and others as late as 412.

16

The temple’s famous Porch of the Maidens, the arrangement of six karyatids holding up the lintel at the southwest corner, is known to every schoolchild who studies Western art (

this page

). But what do we know of the hero for whom the building is named?

The Oxford classicist

Martin West has aptly called

Erechtheus “the big spider at the heart of Attic myth.”

17

The hero is already present in the

Iliad

, wherein Homer says that “Athens, the well built citadel,” is the land of “great-hearted Erechtheus.” Born of the earth, “giver of grain,” Erechtheus was nursed by Zeus’s daughter Athena, who settled him “in her own rich temple” on the Acropolis.

18

In the

Odyssey

this imagery was reversed.

19

It is Athena who enters “the strong house of Erechtheus” atop the Acropolis, presumably a reference to the Mycenaean palace erected here during the Late

Bronze Age (

this page

).

Herodotos tells us that Erechtheus and Athena were worshipped jointly at Athens.

20

The people of

Epidauros made an annual sacrifice to the divine pair, according to an old agreement by which the Epidaurians gained, in return, permission to cut

Athenian olive trees for the carving of sacred statues. Herodotos refers to Erechtheus both as “earth-born” and as “king of the Athenians,” telling us the people first acquired this name during his reign. The temple of Erechtheus, Herodotos also reveals, housed the venerable olive tree and sea spring, tokens of the ancient foundational contest between Athena and

Poseidon.

21

Erechtheus is not always easy to distinguish from a figure known as

Erichthonios, or from a variant named

Erichtheus.

22

These personae share the same extraordinary birth myth, arising directly out of the earth.

23

Each has a wife named

Praxithea.

24

The yoking of horses and the introduction of the chariot are ascribed to both heroes. And both are associated with the Panathenaic festival.

25

That the two share a very unusual birth

myth concerning Hephaistos signals that they are, in fact, one and the same. As we have seen, the smithing god was smitten by the beauty of the maiden goddess Athena. Ignoring her protests, he pursues her but manages only to ejaculate upon her thigh.

26

The unwelcome effluent is wiped away by the chaste goddess

with a piece of wool she discards on the ground. This gesture of disgust results in the impregnation of Mot

her Earth who, in time, gives birth to

Erechtheus/

Erichthonios. It has been argued that the hero’s very name derives from

erion

or

erithechna

(meaning “wool” or “woollen”). Alternatively, it has been seen as deriving from

chthonios

(meaning “belonging to the earth”). Some combine the two and translate “Erechtheus” as “Woolly-Earthy,” though this is unlikely.

27

In Athenian eyes there was only one hero, Erechtheus.

28

He was the primordial king of the polis, born from the earth and nurtured by Athena. But at some point during the fifth century

B.C.

Erechtheus “splits” into two.

29

The construct of “Erichthonios” appears and, by the fourth century, has entirely taken over the early mythologies of the birth and childhood of the hero. Erechtheus then develops into a persona exclusively associated with the mature king of Athens who sacrificed his daughter and fought the war against Eumolpos.

30

Erechtheus and Erichthonios thus come to be perceived as two distinct personalities or, possibly, a younger and older version of the same individual. Erichthonios is always depicted in Greek art as a child or baby, sometimes shown accompanied by guardian snakes.

31

Erechtheus, on the other hand, is always portrayed as an adult, the mature king of Athens.

32

A red-figured vase in Berlin, dating to the third quarter of the fifth century

B.C.

, shows the two heroes together, each labeled by name: Erichthonios as a baby and Erechtheus as an adult (previous page and above).

33

Some have argued on this basis that the two are completely separate individuals.

34

We must, however, take care not to read visual culture too literally. The image-generating process, like the mythopoetic, is complex and nonlinear.

35

It is fully possible to have two aspects of one hero portrayed on a single vase, just as it is feasible for Erechtheus to “split” into two personae. The dynamic character of myth and the processes through which images are created and used allows for far more flexibility than some modern interpreters might like.