The Oxford History of World Cinema (44 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

I am the serial. I am the black sheep of the picture family and the reviled of critics. I am

the soulless one with no moral, no character, no uplift. I am ashamed. . . . Ah me, if I

could only be respectable. If only the hair of the great critic would not rise whenever I

pass by and if only he would not cry, 'Shame! Child of commerce! Bastard of art!'

('The Serial Speaks',

New York Dramatic Mirror

, 19 August 1916)

It is rare indeed for a promotional article in the 1910s to lapse, however briefly, from the

film industry's perennial mantra, 'We are attracting the better classes; We are uplifting the

cinema; We are preserving the highest moral and artistic standards . . .' Probably few

readers ever took such affirmations as anything more than perfunctory, and dubiously

sincere, reassurances to a cultural establishment that approached the cinema with an

unpredictable mixture of hostility and meddlesome paternalism. Nevertheless, it is

unusual -- and telling -- that a studio mouthpiece (in this case, George B. Seitz, Pathé's

serial tsar) should see fit to abandon the 'uplift' conceit altogether. Clearly, it was

impossible even to pretend that the serial played any part in the cinema's putative

rehabilitation. The serial's intertextual background doomed it to disrepute. Growing

directly out of late nineteenth-century working-class amusements -- popular-priced stage

melodrama (of the buzz-saw variety), and cheap fiction in dime novels, 'story papers',

feuilletons, and penny dreadfuls -- the serial was geared to a decidedly lowbrow audience.

As early titles like The Perils of Pauline, The Exploits of Elaine, The House of Hate, The

Lurking Peril, and The Screaming Shadow make obvious, serials were packaged

sensationalism. Their basic ingredients come as no surprise: as Ellis Oberholtzer,

Pennsylvania's cranky head censor in the 1910s, described the genre, 'It is crime,

violence, blood and thunder, and always obtruding and outstanding is the idea of sex.'

Elaborating every form of physical peril and 'thrill', serials promised sensational spectacle

in the form of explosions, crashes, torture contraptions, elaborate fights, chases, and last-

minute rescues and escapes. The stories invariably focused on the machinations of

underworld gangs and mystery villains ('The Hooded Terror', 'The Clutching Hand', etc.)

as they tried to assassinate or usurp the fortunes of a pretty young heroine and her

heroboyfriend. The milieu was an aggressively non-domestic, 'masculine' world of hide-

outs, opium dens, lumber mills, diamond mines, abandoned warehouses-into which the

plucky girl heroine ventured at her peril.

Serials were a hangover from the nickelodeon era. They stood out as mildly 'shameful' at

a time when the film industry was trying to broaden its market by making innocuous

middlebrow films suitable for heterogeneous audiences in the larger theatres being built at

the time. Rather than catering to 'the mass' -- a homogeneous, 'classless' audience fancied

by the emerging Hollywood institution -- serials were made for 'the masses' -- the

uncultivated, predominantly working- and lower-middle-class and immigrant audience

that had supported the incredible 'nickelodeon boom'. Oberholtzer again offers a sharp

assessment:

The crime serial is meant for the most ignorant class of the population with the grossest

tastes, and it principally flourishes in the picture halls in mill villages and in the thickly

settled tenement houses and low foreign-speaking neighborhoods in large cities. Not a

producer, I believe, but is ashamed of such an output, yet not more than one or two of the

large manufacturing companies have had the courage to repel the temptation to thus swell

their balances at the end of the fiscal year.

Serials were also a proletarian product in Britain (and probably everywhere else). A writer

in the

New Statesman

in 1918 observed that British cinema-goers paid much higher ticket

prices than the Americans, but he notes an exception to this rule:

Only in those ramshackle 'halls' of our poorer streets, where noisy urchins await the next

episode of some long since antiquated 'Transatlantic Serial' does one notice the proletarian

invitation of twopenny and fourpenny seats.

Almost never screened in large first-run theatres, serials were a staple of small, cheap

'neighbourhood' theatres (for all intents and purposes, these theatres were simply

nickelodeons that had survived into the 1910s). Although the serious money was in big

first-run theatres, small theatres still constituted the large majority in terms of sheer

numbers, and the studios, despite their uplift proclamations, were reluctant to give up this

lowbrow market.

WHY SERIALS?

The film industry turned to serials for a number of reasons, aside from the ease of tapping

into an already established popular market for sensational stories. It saw the commercial

logic of adopting the practice of serialization, already a mainstay of popular magazines

and newspapers. With every episode culminating in a suspenseful cliffhanger ending, film

serials encouraged a steady volume of return customers, tantalized and eager for the fix of

narrative closure withheld in the previous instalment. In this system of deliberately

prolonged desire punctuated by fleeting, intermittent doses of satisfaction, serials

conveyed a certain acuity about the new psychology of consumerism in modern

capitalism.

Serials also made sense, from the studios' perspective, because, at least in their earliest

years, they represented an attractive alternative for manufacturers who were incapable or

unwilling to switch over to five- and six-reel feature films. Released one or two reels at a

time for a dozen or so instalments, serials could be pitched as 'big' titles without overly

daunting the studios' still relatively modest production infrastructure and entrenched

system of short-reel distribution. For several years, serials were, in fact, billed as 'feature'

attractions -- the centrepiece of a short-reel 'variety' programme. Later, as real feature

films became the main attraction, serial instalments were used to fill out the programme,

along with a short comedy and newsreel.

Serials appeared at a pivotal moment in the institutional history of film promotion:

producers were just realizing the importance of 'exploitation' (i.e. advertising), but were

still frustrated by brief film runs that kept advertising relatively inefficient. As late as

1919, only about one theatre in a hundred ran films for an entire week, one in eight ran

them for half a week, and over four out of five changed films daily. In this situation,

serials were ideal vehicles for massive publicity. They allowed the industry to flex its

exploitation muscle, since each serial stayed at a theatre for three to four months. Serial

producers invested extremely heavily in newspaper, magazine, trade journal, billboard,

and tram advertising, as well as grandiose cash-prize contests. Serials helped inaugurate

the ' Hollywood' system of publicity in which studios paid more for advertising than for

the production of the film itself.

The emergence of serials was linked to one form of publicity in particular. Until around

1917, virtually every film serial was released in tandem with prose versions published

simultaneously in newspapers and national magazines. Movies and short fiction were

bound together as two halves of what might be described as a larger, multimedia, textual

unit. These fiction tie-ins -- inviting the consumer to 'Read it Here in the Morning; See it

on the Screen Tonight!' -- saturated the entertainment market-place to a degree never seen

since. Appearing in major newspapers in every big city and in hundreds (the studios

claimed thousands) of provincial papers, the serials' publicity engaged a potential

readership well into the tens of millions. This practice exploded the scope of film

publicity, and paved the way for the cinema's graduation to a truly mass medium.

THE FILMS AND THEIR FORMULAS, 1912-1920

Although series films (narratively complete but with continuing characters and milieu)

had appeared as early as 1908, or earlier if one counts comedy series, the first serial film

proper (with a story-line connecting separate instalments) was Edison's

What Happened

to Mary

, released in twelve monthly 'chapters' beginning in July 1912. Recounting the

adventures of a country girl (and, needless to say, unknowing heiress) as she discovers the

pleasures and perils of big-city life while eluding an evil uncle and sundry other villains,

the story was published simultaneously (along with numerous stills from the screen

version) in

Ladies'

World, a major women's monthly magazine. Although critics derided

the serial as 'mere melodrama of action' and 'a lurid, overdrawn thriller', it was popular at

the box-office, making the actress Mary Fuller, playing Mary Dangerfield, one of the

cinema's first really big (if rather ephemeral) stars. The commercial success of What

Happened to Mary prompted the Selig Polyscope Company and the

Chicago Tribune

syndicate to team up in the production and promotion of The Adventures of Kathlyn,

exhibited and published fortnightly throughout the first half of 1914. In keeping with the

early star system's trope of eponymous protagonists, Kathlyn Williams played Kathlyn

Hare, a fetching American girl who, in order to save her kidnapped father, reluctantly

becomes the Queen of Allahah, a principality in India.

When it became clear that Kathlyn was a huge hit, virtually every important studio at the

time (with the notable exception of Biograph) started making action series and twelve- to

fifteen-chapter serials, almost all connected to prose-version newspaper tie-ins. Kalem

produced The Hazards of Helen, a railway adventure series that ran for 113 weekly

instalments between 1914 and 1917, as well as The Girl Detective series ( 1915), The

Ventures of Marguerite ( 1915), and a number of other 'plucky heroine' series. Thanhouser

had one of the silent era's biggest commercial successes with The Million Dollar Mystery

( 1914), although its follow-up Zudora (

The Twenty Million Dollar Mystery

) was

reportedly a flop. By far the biggest producers of serials in the 1910s were Pathé (its

American branch), Universal, Mutual, and Vitagraph. Pathé relied heavily on its

successful Pearl White vehicles -- The Perils of Pauline ( 1914), The Exploits of Elaine

( 1915 -- and two sequels), The Iron Claw ( 1916), Pearl of the Army ( 1916), The Fatal

Ring ( 1917), The House of Hate ( 1918) (which Eisenstein cites as an influence), The

Black Secret ( 1919), and The Lightning Raider ( 1919) - -as well as numerous serials

starring Ruth Roland and various lesser-known 'serial queens'. Universal, like Pathé, had

at least two serials running at any time throughout the decade. Several were directed by

Francis Ford (John Ford's older brother) and starred the duo of Ford and Grace Cunard:

Lucille Love, Girl of Mystery ( 1914) (the first film Luis Bufiuel recalled ever seeing),

The Broken Coin ( 1915), The Adventures of Peg o'the Ring ( 1916), and The Purple

Mask ( 1916). Mutual signed up Helen Holmes (of

Hazards of

. . . fame) and continued in

the vein of railway stunt thrillers with The Girl and the Game ( 1916), Lass of the

Lumberlands ( 191617), The Lost Express ( 1917), The Railroad Raiders ( 1917), and

others. Vitagraph at first claimed it was offering a 'better grade' of serials for a 'better class

of audience', but in truth its serials are hardly distinguishable from the sensational

melodramas of its competitors.

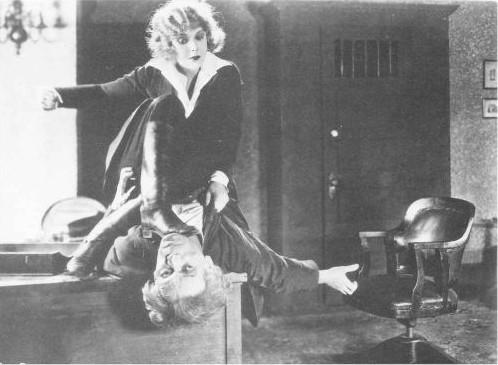

Pearl White in vigorous mode in Plunder ( 1923), her last serial for Pathé in America

grade' of serials for a 'better class of audience', but in truth its serials are hardly

distinguishable from the sensational melodramas of its competitors.

The 1910s was the era of the serial queen. In their stuntfilled adventures as 'girl spies',

'girl detectives', 'girl reporters', etc., serial heroines demonstrated a kind of toughness,

bravery, agility, and intelligence that excited audiences both for its novelty and for its

feminist resonance. Serial queens defied the ideology of female passivity and domesticity,