The Oxford History of World Cinema (41 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

dissonance in literature (Joyce, Stein) and music ( Stravinsky, Schoenberg).

CUBISM

While cubism sought a pictorial equivalent for the newly discovered instability of vision,

the cinema was moving rapidly in the opposite direction. Far from abandoning narrative,

it was encoding it. The 'primitive' sketches of 1895-1905 films were succeeded by a new

and more confidently realist handling of screen space and film acting. Subject-matter was

expanded, plot and motivation were clarified through the fate of individuals. Most

crucially, and in contrast to cubism's display of artifice, the new narrative cinema

smoothed the traces of change in shot, angle of vision, and action by the erasure effect of

'invisible editing' to construct a continuous, imaginary flow.

Nevertheless cubism and cinema are clearly enough products of the same age and within

a few years they were mutually to influence each other: Eisenstein derived the concept of

montage as much from cubist collage as from the films of Griffith and Porter. At the same

time, they face in opposite directions. Modern art was trying to expunge the literacy and

visual values which cinema was equally eager to incorporate and exploit (partly to

improve its respectability and partly to expand its very language).

These values were the basis of academic realism in painting, for example, which the early

modernists had rejected: a unified visual field, a central human theme, emotional

identification or empathy, illusionist surface.

Cubism heralded the broad modernism which welcomed technology and the mass age,

and its openly hermetic aspects were tempered by combining painterly purism with motifs

from street life and materials used by artisans. At the same time, cubism shared with later

European modernism a resistance to many cultural values embodied in its own favourite

image of the new-the cinema, dominated then as now by Hollywood. While painters and

designers could be fairly relaxed in their use of Americana, because independent at this

time of its direct influence, the films of the post-cubist avant-garde are noticeably anti-

Hollywood in form, style, and production.

The avant-garde films influenced by cubism therefore joined with the European art

cinema and social documentary as points of defence against market domination by the

USA, each attempting to construct a model of film culture outside the categories of

entertainment and the codes of fiction. Despite frequent eulogies of American cinema, of

which the surrealists became deliberately the most delirious readers (lamenting the

growing power of illusionism as film 'improved'), few surviving avant-garde films

resemble these icons. Only slapstick, as in Entr'acte ( 1924), was directly copied from the

American example, but this has its roots tangled with Méliès.

ABSTRACTION

The abstract films of Richter, Ruttmann, and Fischinger were based on the concept of

painting with motion, but also aspired towards the visual music implied in such titles as

Richter's Rhythmus series ( 1921-4) and Ruttmann's Opus I-TV ( 1921-5). This wing of

the avant-garde was strongly idealist, and saw in film the utopian goal of a universal

language of pure form, supported by the synaesthetic ideas expressed in Kandinsky's On

the Spiritual in Art, which sought correspondences between the arts and the senses. In

such key works as Circles ( 1932) and Motion Painting ( 1947), Fischinger, the most

popular and influential of the group, tellingly synchronized colour rhythms to the music

of Wagner and Bach.

Fischinger alone pursued abstract animation throughout his career, which ended in the

USA. Other German film-makers turned away from this genre after the mid1920s, partly

because of economic pressure (there was minimal industrial support for the non-

commercial abstract cinema). Richter made lyric collages such as Filmstudie ( 1926),

mixing abstract and figurative shots in which superimposed floating eyeballs act as a

metaphor for the viewer adrift in film space. His later films pioneer the surrealist

psychodrama. Ruttmann became a documentarist with Berlin: Symphony of a City in

1927 and later worked on state-sponsored features and documentaries, including Leni

Riefenstahl's Olympia ( 1938).

SURREALISM

In France, some film-makers, such as Henri Chomette (René Clair's brother and author of

short 'cinema put' films), Delluc, and especially Germaine Dulac, were drawn to theories

of 'the union of all the senses', finding an analogue for harmony, counterpoint, and

dissonance in the visual structures of montage editing. But the surrealists rejected these

attempts to 'impose' order where they preferred to provoke contradiction and

discontinuity.

The major films of the surrealists turned away equally from the retinal vision of form in

movement-explored variously by the French 'impressionists', the rapid cutting of Gance

and L'Herbier, and the German avant-garde -towards a more optical and contestatory

cinema. Vision is made complex, connections between images are obscured, sense and

meaning are questioned. Man Ray's emblematic 1923 Dada film -- its title

Le Retour à la

raison

('Return to reason') evoking the parody of the Enlightenment buried in the name

Cabaret Voltaire -- begins with photogrammed salt, pepper, tacks, and sawblades printed

on the film strip to assert film grain and surface. A fairground, shadows, the artist's studio,

and a mobile sculpture in double exposure evoke visual space. The film ends, after three

minutes, in a 'painterly' shot of a model filmed 'against the light', in positive and negative.

Exploring film as indexical photogram, iconic image, and symbolic pictorial code, its

Dada stamp is seen in its shape, which begins in flattened darkness and ends in the purely

cinematic image of a figure turning in 'negative' space.

Man Ray's later

Étoile de mer

('Star of the sea', 1928), loosely based on a script by the

poet Robert Desnos, refuses the authority of the 'look' when a stippled lens adds opacity

to an oblique tale of doomed love, lightly sketched in with punning intertitles and shots (a

starfish attacked by scissors, a prison, a failed sexual encounter). Editing draws out the

disjunction between shots rather than their continuity, a technique pursued in Man Ray's

other films, which imply a 'cinema of refusal' in the evenly paced and seemingly random

sequences of

Emak Bakia

( 1927) or repeated empty rooms in

Les Mystères du Château

de Dés

('The mysteries of the Chateau de Dés', 1928). While surrealist cinema is often

understood as a search for the excessive and spectacular image (as in dream sequences

modelled on surrealist theory) the group were in fact drawn to find the marvellous in the

banal, which explains their fascination with Hollywood as well as their refusal to imitate

it.

Marcel Duchamp cerebrally evoked and subverted the abstract image in his ironically

titled

Anémic cinéma

( 1926), an anti-retinal film in which slowly rotating spirals imply

sexual motifs, intercutting these 'pure' images with scabrous and near-indecipherable puns

that echo Joyce's current and likewise circular 'Work in Progress',

Finnegans Wake

. Less

reductively than Duchamp, Man Ray's films also oppose 'visual pleasure' and the viewer's

participation. Montage slows or repeats actions and objects (spirals, phrases, revolving

doors and cartwheels, hands, gestures, fetishes, light patterns) to frustrate narrative and

elude the viewer's full grasp of the fantasies film provokes. This austere but playful

strategy challenges the rule of the eye in fiction film and the sense of cinematic plenitude

it aims to construct.

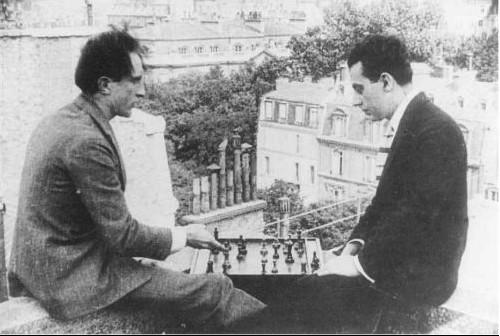

Artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray playing chess in a scene from René Clair's Entr'acte ( 1924)

FROM ENTRACTE TO BLOOD OF A POET

Three major French films of the period -- Clair's

Entr'acte

( 1924), Léger's

Ballet

micanique

('Mechanical Ballet', 1924) and Buñuel's

Un chien andalou

(An Andalusian

dog', 1928) -celebrate montage editing while also subverting its use as rhythmic vehicle

for the all-seeing eye. In Entr'acte, the chase of a runaway hearse, a dizzying roller-

coaster ride, and the transformation of a ballerina into a bearded male in a tutu all create

visual jolts and enigmas, freed of narrative causality.

Ballet mécanique

rebuffs the

forward flow of linear time, its sense of smooth progression, by loop-printing a sequence

of a grinning washerwoman climbing steep stone steps, a Daumier-like contrast to

Duchamp's elegantly photo-cinematic painting Nude Descending a Staircase of 1912,

while the abstract shapes of machines are unusually slowed as well as speeded by

montage. Léger welcomed the film medium for its new vision of 'documentary facts'; his

late-cubist concept of the image as an objective sign is underlined by the film's

Chaplinesque titles and circular framing device-the film opens and closes by parodying

romantic fiction (Madame Léger sniffs a rose in slow motion). Marking off the film as an

object suspended between two moments of frozen time was later used by Cocteau in

Blood of a Poet (

Le Sang d'un poète,

1932), in this case shots of a falling chimney. The

abrupt style of these films evokes earlier, 'purer' cinema; farce in Entr'acte, Chaplin in

Ballet mécanique

, and the primitive 'trick-film' in Blood of a Poet.

These and other avant-garde films all had music by modern composers -- Satie, Auric,

Honegger, Antheilexcept

Un chien andalou,

which was played to gramophone recordings

of Wagner and tangos. Few avant-garde films were shown silently, with the exception of

the austere Diagonal Symphony, for which Eggeling forbade sound. According to Richter

they were even shown to popular jazz. The influence of early film was added to a Dada

spirit of improvisation and admiration for the US cinema's moments of anti-naturalistic

excess. Contributors to a later high modernist aesthetic of which their makers -like

Picasso and Braque -- knew nothing at the time, these avant-garde films convey less an

aspiration to purity of form than a desire to transgress (or reshape) the notion of form

itself, theorized contemporaneously by Bataille in a dual critique of prose narrative and

idealist abstraction. Their titles refer beyond the film medium: Entr'acte ('Interlude') to

theatre (it was premièred 'between the acts' of a Satie ballet),

Ballet mécanique

to dance,

and Blood of a Poet to literature; only

Un chien andalou

remains the mysterious

exception.

The oblique title of

Chien andalou

asserts its independence and intransigence. Arguably

its major film and certainly its most influential, this stray dog of Surrealism was in fact

made before its young Spanish director joined the official movement. A razor slicing an

eye acts as an emblem for the attack on normative vision and the comfort of the spectator

whose surrogate screen-eye is here assaulted. Painterly abstraction is undermined by the

objective realism of the static, eye-level camera, while poetic-lyrical film is mocked by

furiously dislocated and mismatched cuts which fracture space and time, a postcubist

montage style which questions the certainty of seeing. The film is punctuated by craftily

inane intertitles to aim a further blow at the 'silent' cinema, mainstream or avant-garde, by

a reduction to absurdity.

The widely known if deliberately mysterious 'symbolism'of the film -- the hero's striped

fetishes, his yoke of priests, donkeys, and grand pianos, a woman's buttocks that dissolve

into breasts, the death's head moth and ants eating blood-for long dominated critical

discussion, but recent attention has turned to the structure of editing by which these

images are achieved. The film constructs irrational spaces from its rooms, stairways, and

streets, distorting temporal sequence, while its two male leads disconcertingly resemble

each other as their identities blur.

For most of its history, avant-gardes have produced the two kinds of film-making

discussed here; short, oblique films in the tradition of Man Ray, and the abstract German