The Oxford History of World Cinema (46 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Partly in reaction to provincial bannings of

Les Vampires

, Feuillade enlisted the popular

novelist Arthur Bernède (and another cameraman, Klausse) to create more conventional

adventure stories for his next two serials, the hugely successful Judex ( 1917) and La

Nouvelle Mission deJudex

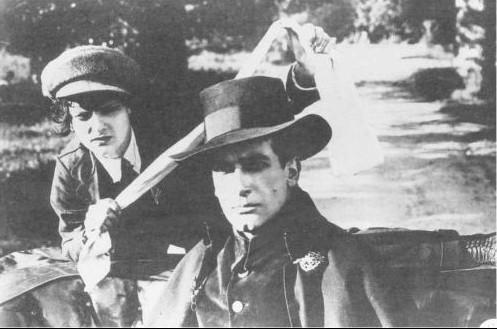

Judex ( 1917)

Judex ( 1918). Wrapped in a black cape and accompained by a sidekick (Marcel

Lévesque), the detective Judex (René Cresté) performed like an updated chivalric hero,

protecting the weak and righting wrongs in order to revenge his father and reclaim the

honour of his name.After the war, Gaumont's production began to decline and Feuillade

made fewer but more diverse films. Serials continued to be his trademark, but they went

through several changes. In Tih-Minh ( 1919), he resurrected the Vampire gang as

displaced 'colonial' antagonists to a French explorer (Cresté) in search of buried treasure

and the love of an Indo-Chinese princess; in

Barrabas

( 1920) he loosed a devious

criminal gang to operate behind the façade of an international bank.

Les Deux Gamines

( 1921),

L'Orpheline

( 1921), and

Parisette

( 1922), however, turned to the very different

formula of the domestic melodrama, focusing on an orphaned

ingénue

heroine (Sandra

Milowanoff) who, after long suffering, married the 'sentimental hero' (in one series, René

Clair). The last of Feuillade's serials took another turn towards historical adventure (soon

to become the trademark of Jean Sapène's Cinéromans), best illustrated in the spectacular

action of

le Fils du flibustier

( 1922). Around this time some of Feuillade's films reverted

to the 'realist' tradition that he had worked in before the war. Using a topical story of

German spies among refugees displaced by the war,

Vendémiaire

( 1919), made with his

last cameraman, Maurice Champreux, documented coat traffic on the Rhone River and

the life of the Bas-Languedoc peasant community during the grape harvest.

Le Gamin de

Paris

( 1923), by contrast, achieved an unusual sense of charm and poignancy through

'naturalistic' acting (by Milowanoff and Poyen), location shooting in the Belleville section

of Paris, skilful studio lighting and set décor (by Robert Jules-Garnier), and American-

style continuity editing. In February 1925, on the eve of shooting another historical serial,

Le Stigmate

(which would be completed by Champreux), Feuillade was taken ill, and dies

of acute peritonitis. RICHARD ABELSELECT FILMOGRAPHYSerials

Bébé

( 1910);

Scènes de la vie telle qu-elle est

( 1911);

Bout-de Zan

( 1912); Fantômas ( 1913); Les

Vampires ( 1915); Judex ( 1917);

La Nouvelle Mission de Judex

( 1918); Tih-Minh

( 1919);

Vendémiaire

( 1919); Barrabas ( 1920);

Les Deux Gamines

( 1921); L'Orpheline (

1921); Parisette ( 1922); Le Fils du flibustier ( 1922); Le Gamin de Paris ( 1923)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abel, Richard ( 1993),

The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema, 1896-1914

.

Lacassin, Francis ( 1964),

Louis Feuillade

.

Roud, Richard (ed.) ( 1980),

Cinema: A Critical Dictionary

(entry on Louis

Feuillade).

NATIONAL CINEMAS

French Silent Cinema

RICHARD ABEL

In 1907, the French press repeatedly erupted in astonishment over the speed with which

the cinema was supplanting other spectacle entertainments like the caféconcert and music

hall and even threatening to displace the theatre. As a song from the popular revue, Tu l'as

l'allure, put it:

So when will the Ciné drop and die? Who knows. So when will the Café-conc' revive?

Who knows.

Whatever the attitudes taken -- and they ranged from exhilaration to resigned dismay --

there was no doubt that, in France, 1907 was 'the year of the cinema' or, as one writer

enthused, 'the dawn of a new age of Humanity'. So limitless seemed the cinema's future

that it set off an explosion of entrepreneurial activity.

PATHÉ-FRÈRES INDUSTRIALIZES THE CINEMA

At the centre of that activity was Pathé- Frères as it systematically industrialized every

sector of the new industry. Two years before, Pathé had pioneered a system of mass

production (headed by Ferdinand Zecca) which soon had the company marketing at least

half a dozen film titles per week (or 40,000 metres of positive film stock per day) as well

as 250 cameras, projectors, and other apparatuses per month. By 1909, those figures had

doubled across the board, and the Pathé studio camera and projector had become the

standard industry models. This production capacity enabled Pathé to construct one cinema

after another in Paris and other cities, beginning in 1906-7, shifting film exhibition away

from the fairgrounds to permanent sites in urban shopping and entertainment districts. By

1909 Pathé had a circuit of nearly 200 cinemas throughout France and Belgium, probably

the largest in Europe. In order better to regulate distribution of its product within that

circuit, in 1907-8 the company also set up a network of six regional agencies to rent,

rather than sell, its weekly programme of films. This network augmented the dozens of

agencies Pathé had opened across the globe, beginning as early as 1904, and through

which it quickly dominated the world-wide sale and rental of films. By 1907, one-third to

one-half of the films making up American nickelodeon programmes were Pathé's -- as a

general rule, the company shipped up to 200 copies of each film title to the United States.

As the 'empire' of this first international cinema corporation began to stabilize (and

eventually contract in the USA because of MPPC restrictions) and film distribution and

exhibition became its most secure sources of revenue, Pathé gradually shifted film

production to a growing number of quasi-independent affiliates. By 1913-14, Pathé Frères

had become a kind of parent company ( Charles Pathé himself invoked the analogy of a

book publisher) to a host of production affiliates, from France (SCAGL, Valetta, and

Comica) to Russia, Italy, Holland, and the USA.

The other French companies engaged in the cinema's expansion either followed Pathé's

lead or found a profitable niche in one or more sectors of the industry. Léon Gaumont's

company, Pathé's closest rival, was the only other vertically integrated corporation active

in every sector, from manufacturing equipment to producing, distributing, and exhibiting

films. Its 1911 renovation of the Gaumont-Palace (seating 3,400 people), for instance, not

only anchored its own circuit of cinemas but spurred the construction of more 'palace'

cinemas in Paris and elsewhere. Unlike Pathé, however, Gaumont steadily increased

direct investment in production so that it too could release at least half a dozen film titles

per week. Under the management of Charles Jourjon and Marcel Vandal, Éclair operated

within a slightly narrower sphere, having never established a circuit of cinemas to present

its product. Instead, to fuel its aggressive expansion between 1910 and 1913, Éclair

concentrated on producing and distributing films as well as manufacturing various kinds

of apparatuses. Along with Pathé, it was the only French company with the capital and

foresight to open its own production studio in the USA. Most smaller French companies

either confined their efforts to production (Film d'Art, Eclipse, and Lux) or concentrated

on distribution (AGC). The most important independent distributor, Louis Aubert,

embarked on a somewhat different trajectory, much as Universal, Fox, and Paramount

would slightly later in the USA. Aubert's company prospered through its exclusive

contracts to release films by the major Italian and Danish producers in France, including

Quo vadis?; by 1913 Aubert was reinvesting his profits in a circuit of 'palace' cinemas in

Paris as well as a new studio for producing his own films.

What kinds of films dominated French cinema programmes during this period, and what

specific titles could be singled out as significant? The actualités, trick films, and féeries

which once characterized the early 'cinema of attractions' had, by 1907, given way to a

more fully narrativized cinema, especially through Pathé's standardized production of

comic chase films and what its catalogue advertised as 'dramatic and realist' films, often

directed by Albert Capellani. The latter category covered domestic melodramas such as

La Loi du pardon ('The law of pardon', 1906), in which families were threatened with

dissolution and then securely reunited, and Grand Guignol variants such as Pour un

collier! ('For a necklace!', 1907), in which the resolution was anything but secure. Within

such films there coalesced a system of representation and narration that relied not only on

longtake tableaux (recorded by Pathé's 'trademark' waist-level camera), bold red

intertitles, inserted letters, and accompanying sound effects but on changes in framing

through camera movement, cut-in close shots, point-ofview shots, and reverse-angle

cutting as well as on various forms of repetition and alternation in editing. This system

achieved remarkable effects in melodramas as diverse as The Pirates ( 1907), A Narrow

Escape ( 1908) (which D. W. Grif fith remade in 1909 as The Lonely Villa), and

L'Homme aux gants blancs ('The man with white gloves', 1908) as well as in comic films

like Ruse de mari ('The husband's trick', 1907) and Le Cheval emballé ('The wrapped-up

horse', 1908). In other words, Pathé films were deploying most of the elements so basic to

the system of narrative continuity, all of which historians still often attribute to slightly

later Vitagraph or Biograph films.

Another instance of increasing standardization within the French cinema was the

continuing series, a marketing strategy in which one film after another could be organized

around a central character (identified by name) and a single actor. As early as 1907, Pathé

began releasing a comic series entitled Boireau, named after a recurring character played

by André Deed. Boireau's success soon led to other comic series (especially after Deed

left France to work in Italy as Cretinetti). In 1909 Gaumont introduced its Calino series,

with Clément Migé often playing a bumbling civil servant; the following year there was

the Bébé series, with René Dary; two years later came the incredibly wacky Onésime

series, with Ernest Bourbon, and Bout-deZan, with René Poyen as an even more

threatening enfant terrible. As for Pathé itself, among the half-dozen comic series it

regularly distributed, two stood out above the rest. One was Rigadin, starring Charles

Prince as a parodic white-collar Don Juan; Le Nez de Rigadin ('Rigadin's Nose', 1911),

for instance, ruthlessly mocks his large upturned nose, one of the comic's singular assets.

The other starred Max Linder, usually as a young bourgeois dandy, and quickly made him

'the king of the cinematograph'. Skilful, cleverly structured gags distinguish Linder's work

from La Petite Rosse ('The little nag', 1909) through Victime du quinquina ('Quinine

victim', 1911) to Max pidicure ('Max the pedicure', 1914). So popular was the comic

series that Éclair, Eclipse, and Lux all made them a regular part of their weekly

programmes. The one variation on this strategy came from Éclair. Victorin Jasset's Nick

Carter series ( 1908-10) drew its formula from the American detective dime novels just

being translated into French and proved such a success that Éclair soon adapted others,

making the male adventure series a trademark of its production.

Together with these standardization practices came a concerted attempt to legitimize the

cinema as a respectable cultural form. Here, the trade press was unusually active,

especially Phono-Ciné-Gazette ( 1905-9), edited by Pathé's collaborator, the Paris lawyer

Edmond Benoît-Lévy, and Ciné-Journal ( 1908-14), edited by Georges Dureau. Yet these

efforts at legitimization were most visible in the production of literary adaptations or

films d'art, led by Film d'Art and SCAGL, new companies with close ties to prestigious

Paris theatres. The earliest and best known of these was Film d'Art's L'Assassinat du Duc