The Oxford History of World Cinema (39 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Nikolai II and Lev Tolstoy (

Rossiya Nikolaya II i Lev Tolstoy,

1928), made for the

centennial of Tolstoy's birth and using film from the 1897-1912 era. The Fall of the

Romanov Dynasty displays a Marxist analysis attuned to the social and economic

conditions that culminated in the First World War and the overthrow of the Tsar. Through

the powerful juxtapositions of images, it initially explicates the functionings of a

profoundly conservative society by examining class relations (landowning gentry and

peasants, capitalists and workers), the role of the State (the military, subservient

politicians in the Duma, appointed governors and administrative personnel, with Tsar

Nikolai perched at the top), and the mystifying role of the Russian Orthodox Church. The

international struggle for markets unleashes the forces of war leading to devastating

slaughter, and ultimately to the February 1917 Revolution that brought Alexander

Kerensky to power. The images are often striking in their composition or subject-matter,

but Shub's framework attaches significance to even the most clichéd scenes, such as

marching soldiers.

POLITICAL DOCUMENTARY IN THE WEST

Non-fiction film-making of an overtly political nature also went on in the United States

and western Europe after the First World War. Short news and information films on

strikes and related activities were made by unions and leftist political parties in many

countries. In the United States, Communist activist Alfred Wagenknecht produced The

Passaic Textile Strike ( 1926), a short feature that combined documentary scenes with

studio re-enactments, while the American Federation of Labor produced Labor's Reward (

1925). In Germany, Prometheus, formed by Willi Münzenberg, produced such

documentaries as The Document of Shanghai (

Das Dokument von Shanghai,

1928),

which focused on the March 1927 revolutionary uprisings in China. The German

Communist Party subsequently produced a number of short documentaries, including

Slatan Dudow's

Zeitproblem: wie der Arbeiter wohnt

('Contemporary problem: how the

worker lives', 1930). Large corporations, right-wing organizations, and government also

used non-fiction film for purposes of propaganda.

In contrast to these breaks with pre- First World War non-fiction screen practices, the new

documentary appeared late in Britain, and in a modest form -- John Gri erson 's Drifters

( 1929), a fifty-eight-minute silent documentary about the fishing process. It focuses on a

fishing boat that drifts for herring, and the people who pull in the nets and pack the fish in

barrels for market. It combines a Flaherty-style plot of man versus nature with partially

abstracted close-ups and a rhythmic editing pattern learned from careful scrutiny of

Eisenstein's Potemkin ( 1925). As Ian Aitken has remarked, Grierson was seeking to

express a reality that transcended specific issues of exploitation and economic hardship.

Nevertheless, Grierson relegated the people who did the actual work to his film's

periphery, even as he synthesized the familiar narrative of a production process with

modernist aesthetics. The film enjoyed a strong critical success, suggesting the extent to

which the British documentary had lost its way in the years since the First World War, but

also the potential for renewal in the 1930s and beyond.

During the 1920s, documentary film-makers struggled either at the margins of

commercial cinema or outside it altogether. Despite the comparatively inexpensive nature

of documentary production, even the most successful films did little more than return

their costs. The general absence of profit motive meant that documentarians had other

reasons for film-making, and often had to rely on sponsorship (as Flaherty did with

Nanook), or self-financing. Although conventional travelogues had a long-standing niche

in the market-place, outside the Soviet Union there was little or no formal or institutional

framework to support more innovative efforts at production.

Despite their low returns, in the industrialized nations non-fiction programmes were

shown in a wide range of venues. In the United States, films such as Nanook of the North,

Berlin: Symphony of a City, and The Man with the Movie Camera enjoyed regular

showings at motion picture theatres in a few large cities and so were reviewed by

newspaper critics, with varying degrees of perspicacity ( Berlin was considered to be a

disappointing travelogue by New York critics). Films such as Manhatta were sometimes

shown as shorts within the framework of mainstream cinema's balanced programmes, and

avant-garde documentaries were often shown at art galleries. In Europe, the network of

ciné clubs provided an outlet for many artistically and politically radical documentaries.

Cultural institutions and political organizations of all types screened (and occasionally

sponsored) documentaries as well. Even in the Soviet Union, prominent documentaries

quickly departed town-centre theatres for extended runs at workers' clubs. Because most

non-fiction programmes generally had some kind of educational or informational value,

they penetrated into all aspects of social life and were shown in the church, the union hall,

the school, and cultural institutions like the Museum of Natural History ( New York). By

the end of the 1920s, then, documentary was a broadly diffused if financially precarious

phenomenon, characterized by its diversity of production and exhibition circumstances.

Bibliography

Aitken, Ian ( 1990),

Film and Reform: John Grierson and the Documentaty Film

Movement

.

Barnouw, Erik ( 1974),

Documentaty

.

Brownlow, Kevin ( 1979),

The War, the West and the Wilderness

.

Calder-Marshall, Arthur ( 1963),

The Innocent Eye: The Life of Robert J. Flaherty

.

Cooper, Merian C. ( 1925),

Grass

.

Flaherty, Robert J. ( 1924),

My Eskimo Friends

.

Hall, Stuart ( 1981),

The Whites of their Eyes

.

Holm, Bill, and Quimby, George Irving ( 1980),

Edward S. Curtis in the Land of the War

Canoes

.

Jacobs, Lewis (ed.) ( 1979),

The Documentary Tradition

.

Musser, Charles, with Nelson, Carol ( 1991),

High-Gass Moving Pictures: Lyman H.

Howe and the Forgotten Era of Traveling Exhibition, 1880-1920

.

Vertov, Dziga ( 1984),

Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov

.

Dziga Vertov (1896-1954)

Denis Arkadevich ( David Abramovich) Kaufman, later to become famous under the

name Dziga Vertov, was born in Bialystok (now in Poland), where his father was a

librarian. His younger brothers both became cameramen: Mikhail (born 1897) worked

with Vertov until 1929, while the youngest, Boris (born 1906) emigrated first to France

(where he shot Jean Vigo's films) and then to America (where he won an Academy Award

for On the Waterfront).

Starting his career with the conventional newsreel

Kino-Nedelia

('Film-Weekly', 1918-

19), Vertov rapidly absorbed ideas shared by left-wing and Constructivist artists

( Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Varvara Stepanova) and Proletkult theorists

( Alexander Bogdanov, Alexei Gan). The documentary and non- or antifictional character

of his cinema was conceptualized in the context of the 'mortification of art' in the future

proletarian culture, and the 'kinoki' (cine-eye) group, with Kaufman, Vertov, and his

(second) wife Elizaveta Svilova as its core, saw themselves as the Moscow headquarters

of a national network (which never materialized) of local cine-amateurs providing

continuous flow of newsreel footage. Later the network was supposed to be supplemented

by a 'radio-ear' component to finally merge into the 'radio-eye', a global TV of the future

socialist world with no place for fictional stories. Vertov's crusade against the fiction film

was intensified after 1922 when Lenin's New Economic Policy led to an increase in

fiction film imports, but he was equally scathing about the new Soviet cinema of

Kuleshov and Eisenstein, describing it as 'the same old crap tinted red'.

The polar tenets of Vertov's theory were 'life caught unawares' and 'the Communist

deciphering of reality'. The 'kinoki' worked on two series of newsreels at the same time:

Kino-pravda

('Cine-truth') grouped facts in a political perspective, while the more

informal

Goskinokalendar

('State film calendar') arranged them in a casual home-movie

style. Gradually the orator in Vertov took the upper hand: between 1924 and 1929 the

style of his feature-length drifted from the diary style towards 'pathos', while

Kino-glaz

('Cine-eye', 1924) foregrounded singular events and individual figures. In accordance

with the trend at the time towards the monumental, Shagai, Soviet! ('Stride, Soviet!',

1926) was conceived as a 'symphony of work', and the poster-style The Eleventh Year

( 1928) as a 'hymn' celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Revolution.

Despite the self-effacing 'we' of the manifestos, the film practice of the 'kinoki' was

largely defined by Vertov's own highly individual amalgam of interests in music, poetry,

and science. Four years of music lessons followed by a year of studies at the Institute of

Neuropsychology in Petrograd ( 1916) led him to create what he later called the

'laboratory of hearing'. Inspired by the Italian Futurist Manifestos (published in Russia in

1914) and the trans-sense poetry (

zaum

) practised by Russian and Italian futurist poets,

Vertov's acoustic experiments ranged from mixing fragments of stenographically

registered speech and gramophone records to verbal rendering of environmental noises

such as the sound of a saw-mill. After 1917, the futurist cult of noises was given a

revolutionary tinge by Proletkult as part of the 'art of production', and urban cacophonies

remained significant for Vertov throughout the 20s. He took part in the citywide

'symphony of factory whistles' (with additional sound effects of machine-guns, marine

cannons, and hydroplanes) staged in Baku in 1922, and his first sound film, Enthusiasm

( 1930) employed a similar noise symphony for its soundtrack.

No less important was his suppressed passion for poetry. All his life Vertov wrote poetry

(never published) in the style of Walt Whitman and Vladimir Mayakovsky, and in his

films of 1926-28 Vertov the poet emerges through profuse titling, particularly convoluted

in One Sixth of the World ( 1926) with its editing controlled by Whitmanesque intertitles:

'You who eat the meat of reindeer [image] Dipping it into warm blood [image] You

sucking on your mother's breast [image] And you, highspirited hundred-years-old man',

etc. While some critics declared that such editing inaugurated a new genre of 'poetic

cinema' ( Viktor Shklovsky went so far as to see in the film traditional forms of the

'triolet'), others found it inconsistent with the LEF (Left Front) doctrine of 'cinema of

facts' to which the 'kinoki' formally subscribed.

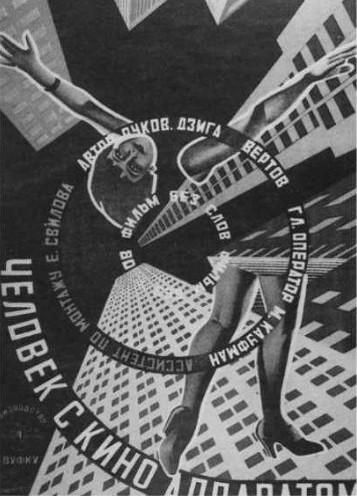

Original poster for The Man with the Movie Camera ( 1929)

In response to these Criticisms, Vertov ruled out the use of all intertitles from his filmic

manifesto The Man with the Movie Camera (

Chelovek s kinoapparatom,

1929), a

tour de

force

which results in what appears to be the most 'theoretical' film of the silent era self-

confined to the image alone. Documentary in material but utopian in essence (its setting

was a nowhere city, a composite location of bits of Moscow, Kiev, Odessa, and a coal-

mining region of the Ukraine), The Man with the Movie Camera summarized the thematic

universe of the 'kinoki' movement: the image of the worker perfect as the machine, that of

the film-maker as socially useful as the factory worker, together with that of the super-

sensitive spectator reacting to no matter how complicated a message the film offers to his

or her attention. In 1929, however, all these quixotic images were hopelessly out of date --

including the master image of the film, that of the ideal city in which private life and the