The Oxford History of World Cinema (40 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

life of the community are harmonized and controlled by the infallible eye of the movie

camera.More personal in style but less original in imagery, Vertov's post-'kinoki' films of

the sound period revolved around songs and music, images of women, and cult figures,

past and present. In Lullaby ( 1937) liberated women sing praise to Stalin, much in the

spirit of the earlier Three Songs of Lenin ( 1934), while Three Heroines ( 1938) shows

women mastering 'male' professions as engineer, piolot, and military officer. These three

films stem back to a project of 1933 carrying the generic title 'She', a film that was

supposed to 'race the working of the brain' of a fictional composer as he writes an

eponymous symphony of womanhood across the ages.Under Stalin, Vertov's feature-

length documentaries were largely suppressed: although never arrested, he was

blacklisted during the anti-Semitic campaign of 1949. He died of cancer on 12 February

1954.

YURI TSIVIAN

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Kinonedelia ( 1918-19);

Boi pod

Tsaritsynym

('The Battle of Tsaritsyn');

Istoriya grazdanskoi voiny

('History of the Civil

War') ( 1921); Kino-Pravda ( 1922-25);

Goskinokalendar

( 1923-25); Kino-glas ( 1924);

Shagai, Soviet! ('Stride, Soviet!') ( 1926);

Shestaya chast sveta

(One Sixth of the World)

( 1926);

Odinnadsatyi

(The Eleventh Year) ( 1928);

Chelovek s Kinoapparatom

(The Man

with the Movie Camera) ( 1929);

Entuziazm -- simfoniya Donbassa

(Enthusiasm --

Symphony of the Donbas) ( 1930);

Tri pesni o Lenine

(Three Songs of Lenin) ( 1934);

Kolybelnaya

('Lullaby') ( 1937);

Sergo Ordzonikidze

( 1937);

Tri geroini

(Three Heroines)

( 1938);

Tebe, front

('To you, front') ( 1941);

Novosti dnia

('News of the day'; separate

issues) ( 1944-54)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Feldman, Seth ( 1979),

Dziga Vertov: a guide to references and resources

.

Petric, Vlada ( 1987),

Constructivism in Film

.

Vertov, Dziga ( 1984),

Kino-eye

.

Cinema and the Avant-Garde

A. L. REES

Modern art and silent cinema were born simultaneously. In 1895 Cézanne's paintings

were seen in public for the first time in twenty years. Largely scorned, they also

stimulated artists to the revolution in art that took place between 1907 and 1912, just as

popular film was also entering a new phase of development. Crossing the rising barriers

between art and public taste, painters and other modernists were among the first

enthusiasts for American adventure movies, Chaplin, and cartoons, finding in them a

shared taste for modern city life, surprise, and change. While the influential philosopher

Henri Bergson criticized cinema for falsely eliding the passage of time, his vivid

metaphors echo and define modernism's attitude to the visual image: 'form is only the

snapshot view of a transition.'

New theories of time and perception in art, as well as the popularity of cinema, led artists

to try to put 'paintings in motion' through the film medium. On the eve of the First World

War, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, author of The Cubist Painters ( 1913), explained the

animation process in his journal

Les Soirées de Paris

and enthusiastically compared

Le

Rythme coloré

('Colour rhythms', 1912-14), an abstract film planned by the painter

Léopold Survage, to 'fireworks, fountains and electric signs'. In 1918 the young Louis

Aragon wrote in Louis Delluc's Le Film that cinema must have 'a place in the avant-

garde's preoccupations.

They have designers, painters, sculptors. Appeal must be made to them if one wants to

bring some purity to the art of movement and light.'

The call for purity -- an autonomous art free of illustration and story-telling -- had been

the cubists' clarion-cry since their first public exhibition in 1907, but the search for 'pure'

or 'absolute' film was made problematic by the hybrid nature of the film medium, praised

by Méliès in the same year as 'the most enticing of all the arts, for it makes use of almost

all of them'. But for modernism, cinema's turn to dramatic realism, melodrama, and epic

fantasy was questioned, in terms reminiscent of the classical aesthetics of Lessing, as a

confusion of literary and pictorial values. As commercial cinema approached the

condition of synaesthesia with the aid of sound and toned or tinted colour, echoing in

popular form the 'total work of art' of Wagnerianism and art nouveau, modernism looked

towards non-narrative directions in film form.

ART CINEMA AND THE EARLY AVANT-GARDE

The early avant-garde followed two basic routes. One invoked the neo-impressionists'

claim that a painting, before all else, is a flat surface covered with colour; similarly, the

avant-garde implied, a film was a strip of transparent material that ran through a projector.

This issue was debated among the cubists around 1912, and opened the way to

abstraction. Survage's designs for his abstract film were preceded by the experiments of

the futurist brothers Ginna and Corra, who hand-painted raw film as early as 1910 (a

technique rediscovered in the 1930s by Len Lye and Norman McLaren). Abstract

animation also dominated the German avant-garde 1919-25, stripping the image to pure

graphic form, but ironically also nurturing a modernist variant of synaesthesia, purging

the screen of overt human action while developing rhythmic interaction of basic symbols

(square, circle, triangle) in which music replaces narrative as a master code. An early

vision of 'Plastic Art in Motion' is found in Ricciotto Canu do 's 1911 essay The Birth of a

Sixth Art, an inspired if volatile amalgam of Nietzsche, high drama, and futurist machine

dynamism.

A second direction led artists to burlesque or parody films which drew on the primitive

narrative mainstream, before (as many modernists believed) it was sullied by realism. At

the same time, these films are documents of the art movements which gave rise to them,

with roles played by -- among others -- Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Erik Satie, and

Francis Picabia (

Entr'acte

, 'Interlude', 1924), and Eisenstein, Len Lye, and Hans Richter (

Everyday, 1929). The ironic humour of modernism was expressed in such films (some

now lost) as

Vita Futurista

( 1916), its Russian counterpart Drama of the Futurist Cabaret

( 1913), its successors in Glumov's Diary ( Eisenstein, 1923) and Mayakovsky's

comicGuignol films, and such later elaborations of cultural slapstick as Clair's classic

Entr'acte ( 1924) and Hans Richter's dark comedy Ghosts before Noon ( 1928). This genre

was explored mostly in the Dada and surrealist tradition, which valued dream-like 'trans-

sense' irrationality as the key trope of film montage and camera image.

An alternative route to the cinema as an art form (the specific meaning of which overrides

the general sense in which all cinema is an art) ran parallel to the artists' avantgarde from

c. 1912 to 1930 and sometimes overlapped with it. The art cinema or narrative avant-

garde included such movements as German Expressionism, the Soviet montage school,

the French 'impressionists' Jean Epstein and Germaine Dulac, and independent directors

such as Abel Gance, F. W. Murnau, and Carl Theodor Dreyer. Like the artist-film-makers,

they resisted the commercial film in favour of a cultural cinema to equal the other arts in

seriousness and depth. In the silent era, with few language barriers, these highly visual

films had as international an audience as the Hollywood-led mainstream they opposed.

Film clubs from Paris to London and Berlin made up a non-commercial screening circuit

for films which were publicized in radical art journals (

G, De stijl

) and specialist

magazines (

Close-Up

,

Film Art

,

Experimental Film

). Conference and festival screenings

-- pioneered by trade shows and expositions such as the 1929 'Film und Foto' in Stuttgart

-- also sometimes commissioned new experimental films, as in the light-play,

chronophotography, and Fritz Lang clips of Kipho ( 1925, promoting a 'kine-foto' fair) by

the veteran cameraman Guido Seeber. Political unions of artists like the November Group

in Weimar Germany also supported the new film, and French cinéclubs tried to raise

independent production funds from screenings and rentals.

For the first decade there were few firm lines drawn by enthusiasts for the 'artistic film' in

a cluster of ciné-clubs, journals, discussion groups, and festivals, as they evenhandedly

promoted all kinds of film experiment as well as minor, overlooked genres such as

scientific films and cartoons which were similarly an alternative to the commercial fiction

cinema. Many key figures crossed the divide between the narrative and poetic avant-

gardes; Jean Vigo, Luis Buñuel, Germaine Dulac, Dziga Vertov, and Kenneth McPherson

of the aptly named Borderline ( 1930-starring the poet H.D., the novelist Bryher, and Paul

Robeson).

The idea of the avant-garde or 'art film' in Europe and the USA linked the many factions

opposed to mass cinema. At the same time, the rise of narrative, psychological realism in

the maturing art cinema led to its gradual split from the anti-narrative artists' avant-garde,

whose 'cinepoems' were closer to painting and sculpture than to the tradition of radical

drama.

Nowhere was this more dramatically the case than in a series of Chinese-style scroll-

drawings made in Swit zerland by the Swedish artist and dadaist Viking Eggeling in

1916-17. These sequential experiments began as investigations of the links between

musical and pictorial harmony, an analogy Eggeling pursued in collaboration with fellow

dadaist Hans Richter from 1918, leading to their first attempts to film their work in

Germany around 1920. Eggeling died in 1925 shortly after completing his Diagonal

Symphony, a unique dissection of delicate and almost art deco tones and lines, its

intuitive rationalism shaped by cubist art, Bergson's philosophy of duration, and

Kandinsky's theory of synaesthesia. It was premièred in a famous November Group

presentation ( Berlin, 1925) of abstract films by cubist, Dada, and Bauhaus artists: Hans

Richter, Walter Ruttmann, Fernand Léger, René Clair, and (with a 'light-play' projection

work) Hirschfeld-Mack.

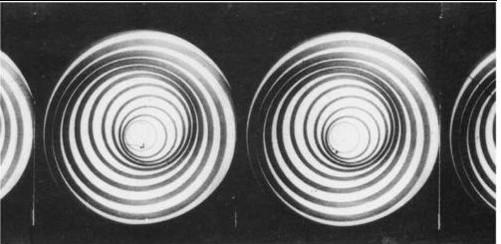

Marcel Duchamp's

Anémic cinéma

The division between the narrative and poetic avantgardes was never absolute, as seen in

the careers of Bufiuel, Vigo (especially in the two experimental documentaries Taris

( 1931), with its slowing of time and underwater shots, and the carnivalesque but also

political film

À propos de Nice

(About Nice', 1930)), and even Vertov, whose Enthusiasm

( 1930) reinvokes the futurist idea of 'noise-music', has no commentary, and is

unashamedly non-naturalistic despite its intended celebration of the Soviet Five-Year

Plan.

Artists' films were underpinned by the flourishing of futurist, constructivist, and dadaist

groups between 1909 and the mid-1920s. This 'vortex' of activity, to use Ezra Pound's

phrase, included the experiments in 'light-play' at the Bauhaus, Robert and Sonya

Delaunay's 'orphic cubism', Russian 'Rayonnisme' and the cubo-futurism of Severini and

Kupka, and its Russian variants in the 'Lef' group. In turn, all of these experiments were,

at least in part, rooted in the cubist revolution pioneered by Braque and Picasso from

1907 to 1912. Cubism was an art of fragments, at first depicting objects from a sequence

of shifting angles or assembling images by a collage of paper, print, paint, and other

materials. It was quickly seen as an emblem of its time-Apollinaire in 1912 was perhaps

the first to evoke an analogy between the new painting and the new physics -- but also as

a catalyst for innovation in other art forms, especially in design and architecture. The

language of visual fragmentation was called by the Fauve painter Derain ( Eggeling's

mentor) in 1905 the art of 'deliberate disharmonies' and it parallels the growing use of