The New Penguin History of the World (34 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

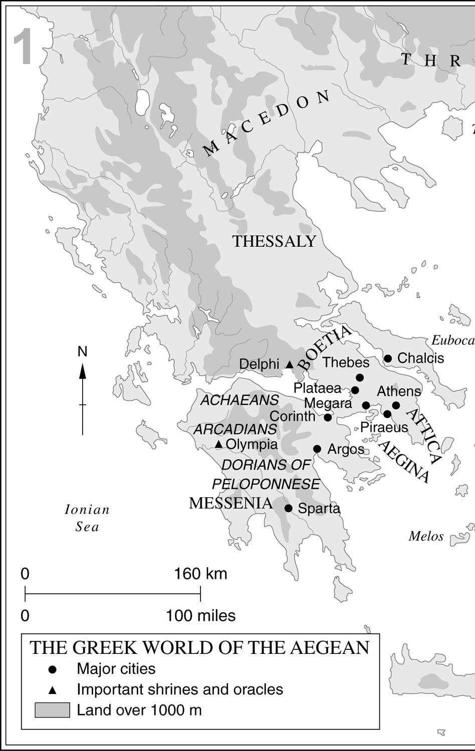

Despite serving in foreign armies, and quarrelling violently among themselves, while cherishing the traditional and emotional distinctions of Boeotian, or Dorian, or Ionian, the Greeks were always very conscious that they were different from other peoples. This could be practically important; Greek prisoners of war, for example, were in theory not to be enslaved, unlike ‘barbarians’. This word expressed self-conscious Hellenism in its essence but is more inclusive and less dismissive than it is in modern speech;

the barbarians were the rest of the world, those who did not speak an intelligible Greek (dialect though it might be) but who made a sort of ‘bar-bar’ noise which no Greek could understand. The great religious festivals of the Greek year, when people from many cities came together, were occasions to which only the Greek-speaker was admitted.

Religion was the other foundation of Greek identity. The Greek pantheon is enormously complex, the amalgam of a mass of myths created by many communities over a wide area at different times, often incoherent or even self-contradictory until ordered by later, rationalizing minds. Some were imports, like the Asian myth of golden, silver, bronze and iron ages. Local superstition and belief in such legends was the bedrock of the Greek religious experience. Yet it was a religious experience very different from that of other peoples in its ultimately humanizing tendency. Greek gods and goddesses, for all their supernatural standing and power, are remarkably human. Much as they owed to Egypt and the East, Greek mythology and art usually present their gods as better, or worse, men and women, a world away from the monsters of Assyria and Babylonia, or from Shiva the many-armed. This was a religious revolution; its converse was the implication that men could be godlike. It is already apparent in Homer; perhaps he did as much as anyone to order the Greek supernatural in this way and he does not give much space to popular cults. He presents the gods taking sides in the Trojan war in postures all too human and competing with one another; while Poseidon harries the hero of the

Odyssey

, Athena takes his part. A later Greek critic grumbled that Homer ‘attributed to the gods everything that is disgraceful and blameworthy among men: theft, adultery and deceit’. It was a world which operated much like the actual world.

The

Iliad

and

Odyssey

have already been touched upon because of the light they throw on prehistory; they were also shapers of the future. They are at first sight curious objects for a people’s reverence. The

Iliad

gives an account of a short episode from a legendary long-past war; the

Odyssey

is more like a novel, narrating the wandering of one of the greatest of all literary characters, Odysseus, on his way home from the same struggle. That, on the face of it, is all. But they came to be held to be something like sacred books. If, as seems reasonable, the survival rate of early copies is thought to give a true reflection of relative popularity, they were copied more frequently than any other text of Greek literature. Much time and ink have been spent on argument about how they were composed. It now seems most likely that they took their present shape in Ionia slightly before 700

BC

. The Greeks referred to their author without qualification as ‘the poet’ (a sufficient sign of his standing in their eyes) but some have found

arguments for thinking the two poems are the work of different men. For our purpose, it is unimportant whether he was one author or not; the essential point is that someone took material presented by four centuries of bardic transmission and wove it into a form which acquired stability and in this sense these works are the culmination of the era of Greek heroic poetry. Though they were probably written down in the seventh century, no standard version of these poems was accepted until the sixth; by then they were already regarded as the authoritative account of early Greek history, a source of morals and models, and the staple of literary education. Thus they became not only the first documents of Greek self-consciousness, but the embodiment of the fundamental values of classical civilization. Later they were to be even more than this: together with the Bible, they became the source of western literature.

Human though Homer’s gods might be, the Greek world had also a deep respect for the occult and mysterious. It was recognized in such embodiments as omens and oracles. The shrines of the oracles of Apollo at Delphi or at Didyma in Asia Minor were places of pilgrimage and the sources of respected if enigmatic advice. There were ritual cults which practised ‘mysteries’ which re-enacted the great natural processes of germination and growth at the passage of the seasons. Popular religion does not loom large in the literary sources, but it was never wholly separated from ‘respectable’ religion. It is important to remember this irrational subsoil, given that the achievements of the Greek élite during the later classical era are so impressive and rest so importantly on rationality and logic; the irrational was always there and in the earlier, formative period with which this chapter is concerned, it loomed large.

The literary record and accepted tradition also reveal something, if nothing very precise, of the social and (if the word is appropriate) political institutions of early Greece. Homer shows us a society of kings and aristocrats, but one already anachronistic when he depicted it. The title of king sometimes lived on, and in one place, Sparta, where there were always two kings at once, it had a shadowy reality which sometimes was effective, but by historical times power had passed from monarchs to aristocracies in almost all the Greek cities. The council of the Areopagus at Athens is an example of the sort of restricted body which usurped the kingly power in many places. Such ruling élites rested fundamentally on land; their members were the outright owners of the estates, which provided not only their livelihood but the surplus for the expensive arms and horses which made leaders in war. Homer depicts such aristocrats behaving with a remarkable degree of independence of his kings; this probably reflects the reality of his own day. They were the only people who counted; other

social distinctions have little importance in these poems. Thersites is properly chastised for infringing the crucial line between gentlemen and the rest.

A military aristocracy’s preoccupation with courage may also explain a continuing self-assertiveness and independence in Greek public life; Achilles, as Homer presents him, was as prickly and touchy a fellow as any medieval baron. To this day a man’s standing in his peers’ eyes is what many Greeks care about more than anything else and their politics have often reflected this. It was to prove true during the classical age when time and time again individualism wrecked the chances of cooperative action. The Greeks were never to produce an enduring empire, for it could only have rested on some measure of subordination of the lesser to the greater good, or some willingnes to accept the discipline of routine service. This may have been no bad thing, but meant that for all their Hellenic self-consciousness the Greeks could not unite even their homeland into one state.

Below the aristocrats of the early cities were the other ranks of a still not very complex society. Freemen worked their own land or sometimes for others. Wealth did not change hands rapidly or easily until money made it available in a form more easily transferred than land. Homer measured value in oxen and seems to have envisaged gold and silver as elements in a ritual of gift-giving, rather than as means of exchange. This was the background of the later idea that trade and menial tasks were degrading; an aristocratic view lingered on. It helps to explain why in Athens (and perhaps elsewhere) commerce was long in the hands of metics, foreign residents who enjoyed no civic privilege, but who provided the services Greek citizens would not provide for themselves.

Slavery, of course, was taken for granted, although much uncertainty surrounds the institution. It was clearly capable of many different interpretations. In archaic times, if that is what Homer reflects, most slaves were women, the prizes of victory, but the slaughter of male prisoners later gave way to enslavement. Large-scale plantation slavery, such as that of Rome or the European colonies of modern times, was unusual. Many Greeks of the fifth century who were freemen owned one or two slaves and one estimate is that about one in four of the population was a slave when Athens was most prosperous. They could be freed; one fourth-century slave became a considerable banker. They were also often well treated and sometimes loved. One has become famous: Aesop. But they were not free and the Greeks thought that absolute dependence on another’s will was intolerable for a free man although they hardly ever developed this notion into positive criticism of slavery. It would be anachronistic to be surprised at this. The whole world outside Greece, too, was organized on the assumption that slavery would go on. It was the prevailing social institution almost

everywhere well into Christian times and is not yet dead. It is hardly cause for comment, therefore, that Greeks took it for granted. There was no task that slavery did not sustain for them, from agricultural labour to teaching (our word ‘pedagogue’ originally meant a slave who accompanied a well-born boy to school). A famous Greek philosopher later tried to justify this state of affairs by arguing that there were some human beings who were truly intended to be slaves by nature, since they had been given only such faculties as fitted them to serve the purposes of more enlightened men. To modern ears this does not seem a very impressive argument, but in the context of the way Greeks thought about nature and man there was more to it than simple rationalization of prejudice.

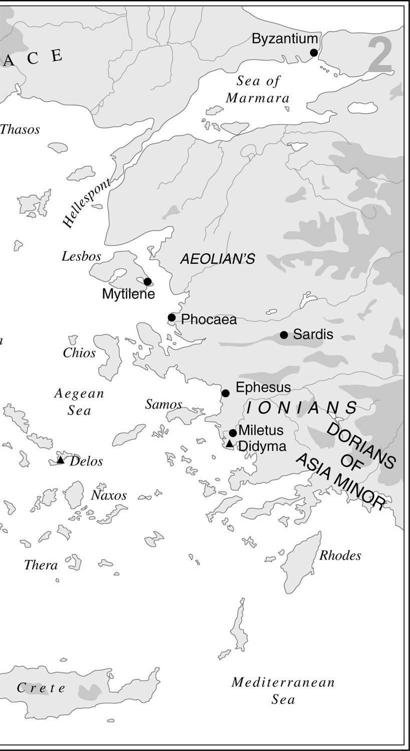

Slaves may and foreign residents must have been among the many channels by which the Greeks continued to be influenced by the Near East long after civilization had re-emerged in the Aegean. Homer had already mentioned the

demiourgoi

, foreign craftsmen who must have brought with them to the cities of the Hellenes not only technical skill but the motifs and styles of other lands. In later times we hear of Greek craftsmen settled in Babylon and there were many examples of Greek soldiers serving as mercenaries to foreign kings. When the Persians took Egypt in 525

BC

, Greeks fought on each side. Some of these men must have returned to the Aegean, bringing with them new ideas and impressions. Meanwhile, there was all the time a continuing commercial and diplomatic intercourse between the Greek cities in Asia and their neighbours.

The multiplicity of day-to-day exchanges resulting from the enterprise of the Greeks makes it very hard to distinguish native and foreign contributions to the culture of archaic Greece. One tempting area is art; here, just as Mycenae had reflected Asian models, so the animal motifs which decorate Greek bronze work, or the postures of goddesses such as Aphrodite, recall the art of the Near East. Later, the monumental architecture and statuary of Greece was to imitate Egypt’s, and Egyptian antiquities shaped the styles of the things made by Greek craftsmen at Naucratis. Although the final product, the mature art of classical Greece, was unique, its roots lie far back in the renewal of ties with Asia in the eighth century. What is not possible to delineate quickly is the slow subsequent irradiation of a process of cultural interplay which was by the sixth century working both ways, for Greece was by then both pupil and teacher. Lydia, for example, the kingdom of the legendary Croesus, richest man in the world, was Hellenized by its tributary Greek cities; it took its art from them and, probably more important, the alphabet, indirectly acquired via Phrygia. Thus Asia received again what Asia had given.

Well before 500

BC

, this civilization was so complex that it is easy to

lose touch with the exact state of affairs at any one time. By the standards of its contemporaries, early Greece was a rapidly changing society, and some of its changes are easier to see than others. One important development towards the end of the seventh century seems to have been a second and more important wave of colonization, often from the eastern Greek cities. Their colonies were a response to agrarian difficulties and population pressure at home. There followed an upsurge of commerce: new economic relationships appearing as trade with the non-Greek world became easier. Part of the evidence is an increased circulation of silver. The Lydians had been the first to strike true coins – tokens of standard weight and imprint – and in the sixth century money began to be widely used in both foreign and internal trade; only Sparta resisted its introduction. Specialization became a possible answer to land shortage at home. Athens assured the grain imports she needed by specializing in the output of great quantities of pottery and oil; Chios exported oil and wine. Some Greek cities became notably more dependent on foreign corn, in particular, from Egypt or the Greek colonies of the Black Sea.